I felt no obligation, only freedom and playfulness

Interview with Dóra Maurer, part 2

Our 94th issue featured the first part of the edited, abridged version of the video interview conducted together with Marcell Esterházy. Here we present the second part of that interview, in which we aimed to highlight additional aspects that are relevant not only in terms of the art of the period, but also with regard to how Dóra Maurer’s work process was developed. (The video version of the interview can be accessed online.)

Dóra Maurer, 1968 © Dóra Maurer, Photo: Tibor Gáyor

Organizing activities

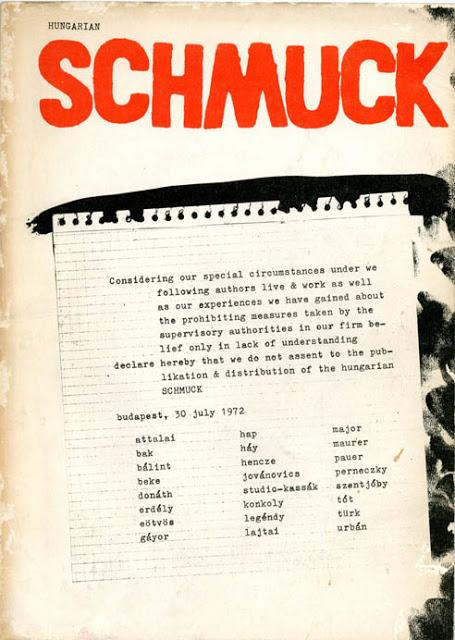

That was when I met Tibor (Tibor Gáyor; this is where part one ended – the editor). At first, we only wanted to live together in Vienna, but then it turned out this was only possible if we got married. And, for that, first you had to come home and wait for one year until all the documents were issued by the authorities. We chose a different path: I stayed in Vienna and, after a month or two, I received a new Hungarian passport... In terms of how Vienna influenced me: when I came home, Tibor’s freshness and interests were giving me new momentum. While I was living in Hungary, I didn’t believe anything could change for the better; I kept my distance from everything and everyone, only maintaining a friendship with Major. For instance, although I had received an invitation, I didn’t go to the Batu Khan lunch [refers to the first happening in Hungary] either; I figured nothing would happen there. Then I finally began to take a look around and realized that there were a lot of interesting things around me that I could engage in. And Vienna was a closed world, one that didn’t let me in. As soon as you are no longer a guest and a foreigner, as soon as you belong there even a little bit, they instantly shut you out. There was a gallery that showed some interest in me – I had an exhibition there – but its milieu prompted feelings of inferiority in me, which was not at all constructive. I only developed a good relationship with the Viennese, when, later on, as a member of the Béla Balázs Studio, I participated in an Austrian film festival there by showing one of my works. Afterwards, someone came up to me from the Austrian group and asked me if I was indeed me, and if I wanted to go along with them. It was Marc Adrian (1930–2008 Austrian visual artist and filmmaker – the ed.) and his circle. After that, Vienna became a friendlier world to me. In ’75, at a different event in Vienna, Peter Weibel was showing videos and, standing in front of the playback equipment, tried to establish a connection with people in the audience. I went up to him and asked: you are Herr Weibel, aren’t you? I immediately invited him to Budapest. This was of interest because, by then, in Hungary, I had been a participant of the otherwise fizzling-out avantgarde movement. Just as Erdély, Beke and a few others, I also maintained a general avantgarde mentality. I originally invited Weibel to have a video presentation at the Ganz-MÁVAG [Ganz Works]. It was our second year there, but it all ended when we were banned from the premises. So the first Hungarian video festival took place in Nap Street, at the Józsefváros Gallery. Peter Weibel had brought with him an approximately 40 cm screen television set and a ton of tapes – so he presented a lot of material, accompanied with explanations. There were at least 150 people in the audience. There was a large lecture hall at the Austrian Cultural Institute where Weibel showed a VALIE EXPORT film and gave a presentation on Eastern European avantgarde in the twenties. But then he tired of always being the one I invited and recommended someone else in his place. Things at home were beginning to pick up; there was an Austrian film screening at the Budapest Gallery and I also organized a British experimental film event at the National Gallery. It became very important to me to introduce these materials in Hungary. If you ask me why this was, my practical answer would be that, around ‘73, I realized no one wanted me – abroad or here – nor were there any events happening that was of real interest to me. This led me to conclude that I had to organize things that were interesting to me. Before, when we were talking off camera, you remarked on how I have always built my own environment. This is why. So I began to organize things, for instance, with Beke’s help. The first event like this was an exhibition in Balatonboglár entitled Szövegek/Texts, which presented an amalgam of concept and visual poetry – actually, this one I actually organized with Gábor Tóth. It was an international exhibition to which Klaus Groh, who was editor of the book Aktuelle Kunst in Osteuropa, sent material as well. He sent not only his own work, but others’ as well. Today, Gábor Tóth is a well-known figure, but, back then, he was still a young boy – though he was interested in Tamkó Sirató’s dimensionism, for example, which I hadn’t heard of before, and Kassák as well. We had further plans; we wanted to present our own rendition of Kurt Schwitters’ Ursonate. I also participated in putting together the periodical Szétfolyóirat [Spreadiodical], organized by Béla Hap – I actually edited an issue. (Unfortunately, all seven copies were lost.) It contained Viennese actionism, concrete poetry, eat art, and my own ideas and plans. I typed on sheets of copy paper – for each theme there was a different colour paper: light green, pink, and white. These were all lost. I gave one to Tamás Vekerdy, who passed it on to Miklós Gábor, who then swallowed it. Their task would have been to copy a part from it and add to it two-thirds’ worth of new material. But this never happened, the whole thing just kind of petered out. One thing brought on another. When, in ‘72, the Aktuelle Kunst in Osteuropa anthology was published by DuMont, Tibor and I happened to be in Cologne. We were delighted to be receiving an author’s copy and we went to the studio to pick it up. There we were told to find Klaus Groh, who lived in Oldenburg, a good distance away from Cologne. We were travelling around a lot anyway, so we didn’t mind so much; we went to Oldenburg. At Groh’s, we met David Mayor, a young man from London who was one of the organizers of Fluxus West. Fluxus West was a little different from the original flux, and – how should I say – its participants were primarily amateurs and individuals who were not as well known. Ken Friedman, a young man from California, was another central figure; he came to Budapest and exhibited at the Young Artists’ Club. Endre Tót was the person he was in contact with in Budapest, whom he sent a box full of his own discarded clothes to be exhibited. Tót was swearing because he had to pay customs duty on it. In Utrecht, we visited concept artist Gerrit Jan de Rook, who wanted to have a concept art show featuring the works of Hungarian artists. Many took part in the exhibition, including Szentjóby, Miki Erdély, and Attila Csáji as well. Gerrit Jan, together with two museum people, later organized a Hungarian constructive touring exhibition, which also stopped in other Dutch museums. So there were quite a few exhibitions organized abroad, which were mediated by Tibor and I, and there were also instances when we transported the material. So it was a lively world. In the meantime, the community of Hungarian avantgarde artists was still around but has somehow lost hope and faith. These exhibitions also served to mobilize them a little bit. Beke was always my partner in this; I sought him out on a number of occasions and he was always absolutely open to collaboration. In fact, he was the well-spring of ideas, the person who was in touch with everyone. For example, David Mayor convinced me to put together an issue of Schmuck, which I could do only with Beke’s help. Schmuck was an English language publication series with national issues; including Japanese and Slovak – that is to say Czechoslovak – issues. Hungarian Schmuck, as Mayor put it, turned out to be a rather ambitious issue. It had a funny cover: there were ominous black fingerprints on it with a paper pasted across them with a statement from the participating artists asserting that they had no knowledge of the publication. This was a precaution as the issue was not approved for publication in Hungary. Tibor and I, when we went to Vienna, we mostly travelled during the night and sometimes all our belongings were searched at the border, even our wallets. On one such occasion. the customs officer told us that he couldn’t ascertain whether our sketches were works of art or not, and works of art could not be transported across the border without the appropriate papers. We tried to explain to him that these were visual thoughts. So, there we were, in the middle of the night, arguing whether it was possible to transport thoughts across the border – or even to think at the border. Such were the absurdities.

It was through Beke that we met Czech artist and art historian Jiří Valoch and Pospíšilova, who mapped out Eastern European art for themselves (they had meant to visit us once before but we were not in Budapest at the time). This acquaintance led to a number of shared projects, which were interrupted by Charter 77, but were then continued. We still maintain a relationship with them today. Indeed, I had built an environment – a kind of milieu – for myself, of which I was at the centre. And others began to ask me if I would include them in the exhibitions. This signified a kind of power, which I didn’t abuse, but I still have guilty feelings about: in effect, I come up with an idea and then drag other people into it. But they are usually happy about it.

Film

Yes, there was always film, even in the midst of my frenzied Thomas Mann-reading periods – based on his stories or my own experiences. For instance, someone in the building I lived in piqued my interest because he reminded me of Little Herr Friedemann and the whole dwarf scenario. Of course, the real situation was entirely different: he had a family, a child. I wanted to shoot a music film with close up shots of musicians as they play their instruments – the saliva as it accidently dribbles from the corner of the a wind instrument player’s mouth, things like that. The kind of thing I wanted to portray was, for example, a man, who falls to the fringes of society because he has a handicap – let’s say he has a hunched back. And he is utterly preoccupied by this handicap and also looks for physical handicaps in others, so he can feel better about himself and tell himself that he is not the only one struggling with such a problem. Of course, nothing came of it; it had remained a dream. Then, around ‘67, I began to think once again about how these film projects could be realized. By then, I was thinking in terms of animation – in terms of moving forms that had been created by etching. And this fit with the question of formation and constant metamorphosis, for which a nonstop animation – or an animation that would return to itself and then change – would have been a good solution. This followed naturally from the etching series that I had already mentioned in connection to my travels abroad. These were at first, while my curiosity still lasted, filled with incredibly strong doses of emotional and cultural charge – in a way, operating as cultural conglomerates. But once my curiosity let up and I was standing there, all emptied out, I began to actively seek out experiences. I turned my attention primarily toward visible movement, like the flow of the Danube, cyclical movements, and shifting movements: what happens if I push an object, causing it to change its place? Then I might as well keep pushing it; dislocation becomes a potentially endless process. And then I figured, I have a material: the etched plate, which, in effect, is created through a cumbersome and slow technique. But one can also think of these copper plates as material that suffers certain movements, which either began and then end somewhere or begin to then never end. So this is where everything originates, from the very meticulous activities of etching, intaglio printing and pressing. By the way, once I went to Rómaifürdő to visit the Peterdis. In front of the public bath, there was a large field that had some paths leading across it. The soil was very supple, obviously wet and clayey. I became interested in the path itself. The path is connected to the mark-making activities of the human being; thus, etching is a possibility for mark-making, for constant change, a process of becoming, etc. Different events that leave marks... Here, of course, photography also entered the picture. I didn’t have a camera, so I used Tibor’s. After that I don’t think he ever had the chance to lay his hands on it again. So, anyway, it all began organically, as a self-evident thing. It was around that time that I wrote the book on etching for the Műhelytitkok [Workshop Secrets] series. Rembrandt’s Three Crosses was a good example for the ruined, used-up plates, which have been used to create one too many prints, causing them to lose their “voice”. This, too is a condition, a state of existence: when they are completely worn down and faded, they signify something utterly different. So all of these things together began to take shape in my mind, and it was from these that I abstracted the concept of displacement. Displacement is a phenomenon that can be traced in a multitude of different ways, in different aspects of life from everyday existence to politics. The best example for this is Poland and how its borders have been pushed back and forth – which is, of course, a horrible thing. So, around ‘69–70, it all came together as a kind of inventory in my mind; how art and life can be drawn together. There is constant displacement in music too, for instance, as we place various notes next to one another; they are almost the same but not quite, thereby creating dissonance and tension, which I am immensely attracted to because, to me, this is what signifies life and movement. But, of course, I simultaneously work with various themes which are sometimes in sharp contrast with one another. I work on one, then the other, or sometimes I “squeeze them into one”. I can also connect this to the fact, which is of course complete silliness, that I’m a Gemini. I know that this is relevant for you, that’s why I brought it up. (laughing)

The cover of the Hungarian Schmuck, 1972 (Din A4)

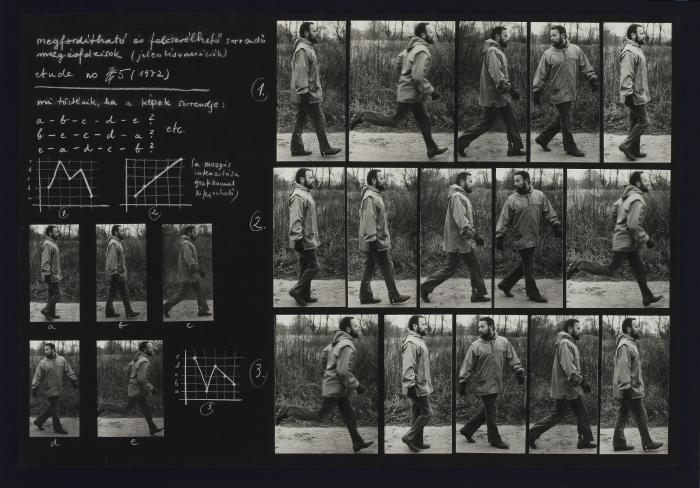

Reversible and interchangeable movement phases, etűd no 5, 1972, photos on wood, white pencil, 100 x 100 cm, performer Gáyor Tibor © Dóra Maurer

Developing her own method

There was a time in the early ‘70s when I also had an “intent of self-expression” but it never bore fruit, at least not directly, since that is not really how self-expression works: when you experience something, you are in it whether you want to be or not. The visceral imprint of this condition will be strong – sad or weak, or funny, or entertaining, or some other thing. So these things should not be bound to intention, because that can only lead to something contrived and artificial; it will not lead to the desired result. It was actually just this morning that I picked up one of my sketchbooks (which I use to jot down things that I find stimulating), where I read something that Anton Webern, whom I am very fond of, said: art should be protected and safeguarded from voluntarism – in other words, from intentionality and wilfulness. To return to my works: my affinity for geometry already showed itself prior to ’56, when I picked up a then current Kassák publication: in addition to some poems (that I didn’t read because I don’t like poetry), it also contained some of his picture architecture drawings, in which, behind one form, another one is visible, and it goes on and on like that. What I do is similar to this, but while I systematize through displacement, he instinctively shifted these shapes back and forth. During theoretical lectures at the Academy, I drew these patterns on the desk. But I knew that these would never turn into art, because I would not make it that far, maybe by the time I turned 60; I was definitely not at that level at the time. I regarded myself as a naturalist and, with reference to that point in time, I was right.

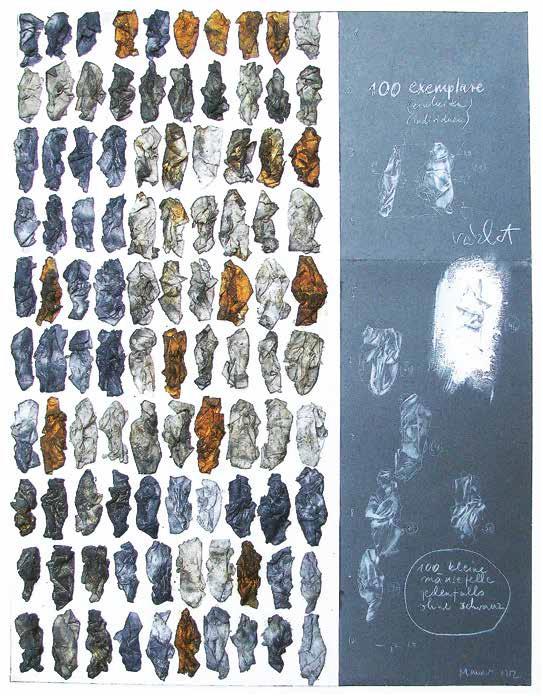

I had a series in which I coloured identically sized pieces of blotting paper with similar earthy colours, then crumpled them into small balls and placed them next to one another, lining them up as if they comprised part of a natural history collection. This was connected with my etching in which I covered a representation of female genitalia with rabbit fur. I didn’t want to directly show it, so I covered it up with rabbit fur. There was a wonderful fur shop in Vác, where I bought a bunch of rabbit and hamster fur. I thought it would be great to also possess a 100 pieces of mouse fur as well, but I couldn’t acquire any – nor did I really want to because I felt sorry for the mice. So I made 100 little paper pellets instead, which documented – or, rather, substituted for – the mouse fur. This brought on the counting, that we should take a10x10-es surface on which we can place things that are either the same or different. This is where the “magic square” idea came from. Which of course I came up with on my own rather than taking it from Dürer, his magic shape in Melancolia; mine had a ton of basic elements, about 500. These had to be positioned so that, added up, the final sum was identical in any direction. I put it together from small branches, shifting it back and forth for weeks. Parallelness, dissimilarity, artificial and natural, covered up and uncovered – these are the concepts that describe it. But the point is that these were not just concepts but also tactile matters. So it was from this that I abstracted the magic square; I drew rectangles with a ratio of 5:4 (I don’t like squares because they are identical in every direction), then shifted these above one another and I thought: this is not really art, this is just counting. It was better, because this way I felt no obligation, only freedom and playfulness. This, in effect, is how my very conscious work with displacement began. But I was also doing some etchings in the meantime: I punched the plate, showed it from the front, from the back, then folded it back, etc. Then there was dropping the plate and keeping a single print that resulted from the event – though this had come earlier. In fact, it wasn’t even using copper plates and mordant, but drypoint needle and aluminium instead, which is very malleable because it’s soft. So the whole process was moving in more of a sketch-oriented, structural direction. These drawings, which were not originally intended as art, led to painting (their later derivate); I distinguished between the individual elements by using coloured lines, which I then thickened and filled in with diagonal lines in order to indicate on the surface what was where. I also noticed that if I used purple last that calmed the whole process. It was in ‘77 that I tried acrylic for the first time, on chipboard cut out in random shapes. Later, I only considered the boundary lines; they determined the outer shape of the object, within which everything else was positioned. This, then, led to virtual space creation, which is how they used to paint objects; one object covered another behind it, creating the impression of three-dimensional space. This was how it happened in my work as well: although it was two-dimensional, it created an experience of space, which couldn’t be done away with. Then I read a pocket sized, illustrated book on psychedelic painting. They took some flats and covered entire parts of them with floating ornamentation which was supposedly a projection or evocation of psychedelic mental states. This gave me the idea that I could fill the walls of an entire room with a painting. Dieter Bogner had an exhibition idea: large-scale artworks. I lined the entire corner of a large room with 150x130 cm pieces of canvas. When he saw this he told me to pick a room in his castle in Lower Austria close to the Czech boarder, which he had inherited from his father and which had an entire wing where nothing was happening. There I discovered a 12th century belvedere with walls that were 1.5 metres thick, which seemed small enough to cover in paint. It took me an entire month – at first three weeks and then I went back to finish it. In the meantime, I was taking photos. In the process I had the realization that photography may be a very comfortable profession, but it cannot really capture the thing in its entirety. I bought a Super 8 camera which had all kinds of features. I filmed myself working and filmed the space as well, as one colour was painted on top of another. Because there were rules to this game, it was constructed according to certain rules. And it was here that I determined the thickness of the different bands and the area that would correspond to these dimensions off the top of my head, without any previously prepared calculations. And the outcome was precise. When you instinctively hit upon something and follow it, and do it well, then it must work. It can’t end up being irregular, or out of place. I still have the film, though I cut a certain part of it because it was boring and there were problems with the music as well; at first I wanted to use a Gregorian chant, which would have sounded a little too glorious – overly suggestive of my joy about this colourful space – so I asked Jeney to compose some music to go with the film, which ended up being so melancholy that, as soon as the film begins, I feel like my heart is breaking.

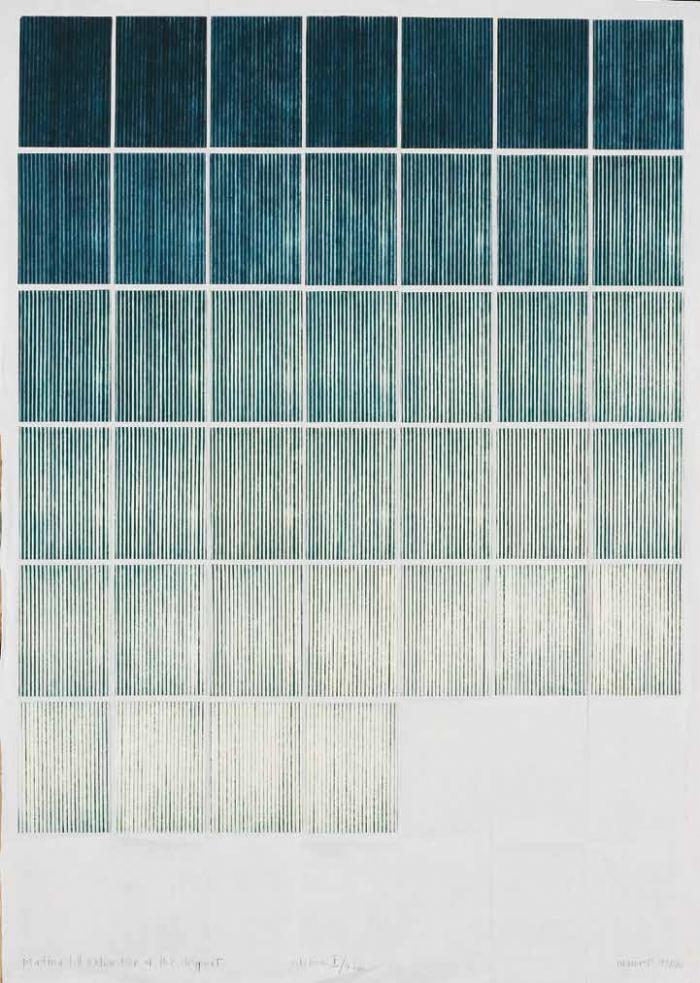

Nyomtatás kimerülésig (Print to exhaustion), line spacing 5 mm, 1979, cold needle etching, 100 x 70 cm, glued on canvas © Dóra Maurer

So it was this movement into space, this painting in space and, especially, the recording that made me realize that it is not only light conditions – or brightness – that are subject to change, but the colours themselves. This was one of the fundamental experiences that prompted me to work more consciously and vigorously with colours. The other one had to do with approaching the whole thing as if I were unfolding a shoebox; I painted the individual elements on the walls, where they belonged. Of course I could have also chosen to project a coherent figure into the space, which would have produced strong distortions on the walls – this, in essence, would have resulted in a kind of anamorphosis. And it was at this point that the intentional realization of a single vantage point perspective emerged as a possibility. I was mainly interested in distortion. Later I even did a series with photographic solutions in which I illuminated the photo paper through a photo magnifier, which I then tilted, folded, creased and turned this way and that. It was around ‘80 that, with a final series, I left etching behind completely. I took small plates and drew densely repeating parallel lines, one next to the other, with a drypoint needle. The distance between the lines followed the beginning of the Fibonacci sequence: 1 mm, then 2, 3, 5 and 8 – the golden ratio, but that is just a formal aspect here. The point is that if the drypoint lines scratched into the surface are densely arranged, catching the paint, they will retain their freshness with repetitive printing a lot longer, they will not flatten out. If they are further apart, they will flatten much quicker. I made many prints with these small plates, waiting to see how long it would take for the plate to “expire”. So this was a process-series. This was the last one, it is entitled Printing till Exhaustion. I have already spoken about the conscious – or, if you will, not constructivist-like – use of perspective, but we now are entering the ‘90s when this spatiality became increasingly dominant in my works. I painted the perspectival forms and the forms originating from shifting the rasters of my own invention – and also made sure that these forms were shown not in plane perspective, but tilted in an irregular manner. This is where the arches come from, which I later laid out on a sphere and systematized; this was another one of those regulatory procedures. In essence, this is where these bi-, tri- and quadricinia that can be seen on the wall here come from. I am beginning to this type of work as shape-athletics, because I come up with one based on the other and I try to create what is still missing. Sometimes I feel doubtful, other times I don’t. But I always connect them to music. I just heard Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21 in C major, which is very close to my heart – it is incredibly beautiful, I just sit there listening in delight. To take sounds and weave them together into something that does not exist in nature… Because the song of a thrush is beautiful too, but this is unparalleled – this combination of sounds requires the human brain. Not emotions as much as the brain, and the whole character of that person. When you create artificial forms, this is what it all comes down to. In effect, this is also a criticism of the socially conscious art we have now, which is so avidly advocated for by many all over the world. Because that is not what it’s about – it is about generating joy. If something works well in the form of joy, then that amounts to a whole lot more than expressing one’s personal view about politics – that never leads to anything, you just get all worked up. I am not saying I’m not a political person, I get myself worked up over everything too, but when I am working, then my head is elsewhere. Or when you hear that someone has suffered a great tragedy and they use their art as an outlet to work through it. When I suffer a great tragedy, I don’t do anything, I experience the tragedy and that’s that. Then, when I manage to get myself together, I start to work again.

100 units (instead of mice fur), 1971, paper collage, ink, white pencil on cardboard, 65 x 50 cm © Dóra Maurer

Mennyiségtábla 4. mágikus négyzet (Quantity table 4th magic square), 1972, oil, wood, 90,5 x 62 cm © Dóra Maurer

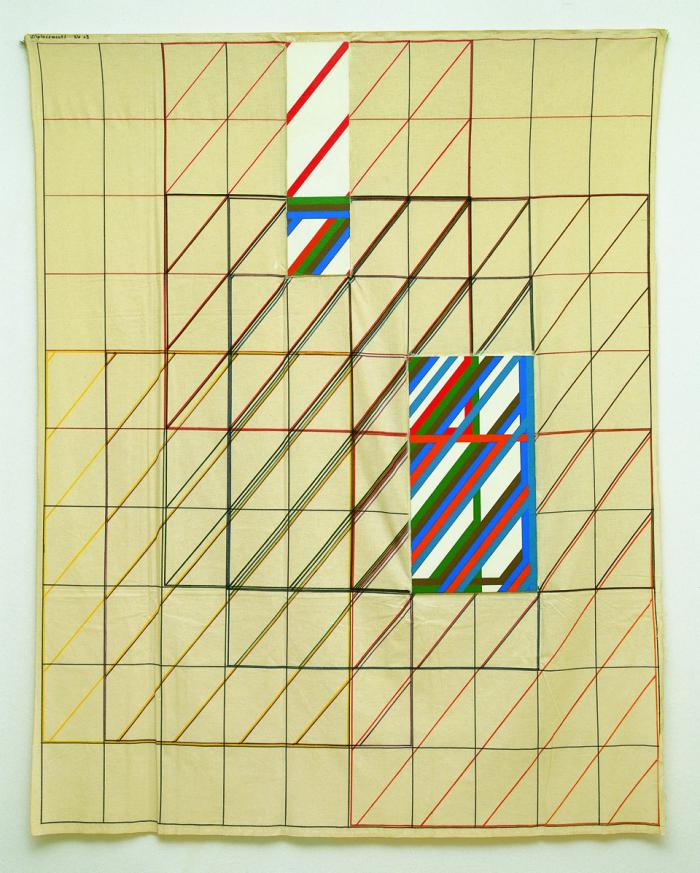

Displacements, 18. lépés két véletlen Quasi-képpel (Displacements, 18th step with two random Quasi images), 1976, cavnas, wood, acrylic, 200 x 160 cm © Dóra Maurer

Quasi-image 2, 1977, plywood, acrylic, 200 x 132 cm © Dóra Maurer

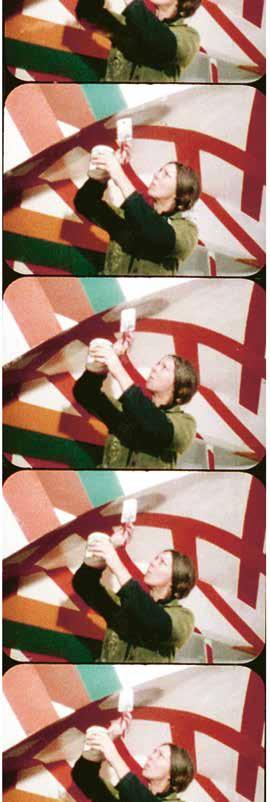

Images from the movie titled Térfestés, Buchberg projekt, 1982, S8 camera Maurer D., 16 mm film, BBS and Exakte Tendenzen Wien/ Buchberg Prod. © Maurer Dóra

Photo: Sulyok Miklós

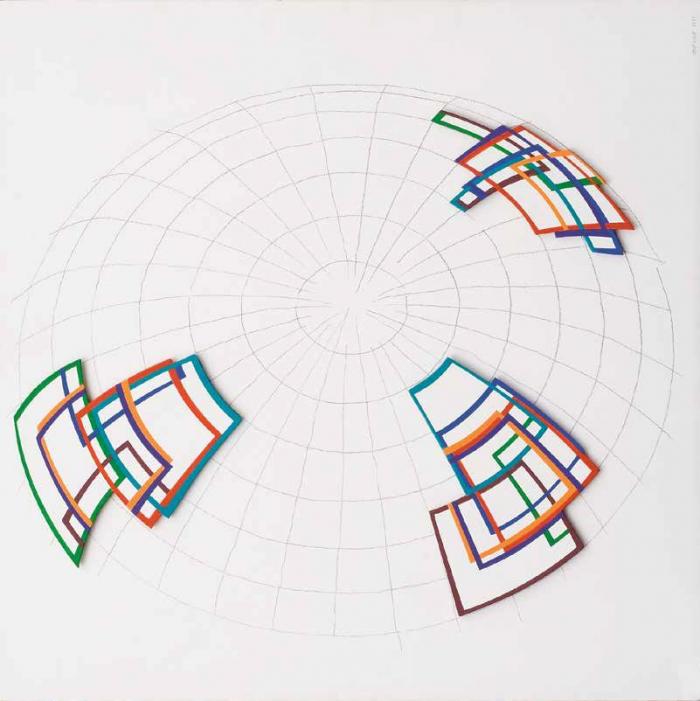

Hemiszferikus hármasikrek (Hemispheric triplets), 1999– 2001, installation with mural, wood, canvas, acrylic, charcoal, 330 x 400 cm © Maurer Dóra

Photo: Sulyok Miklós

Translated by Zsófia Rudnay