Conversation with Ilona Keserü

The Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest and its Paintings: A Place in Memory

It was in 1995 that I read for the first time the interview Ernst H. Gombrich and Neil MacGregor made with Bridget Riley, discussing the collections of the National Gallery in London. At that time, I was already working at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest and I was curious to find out how some of the most significant Hungarian artists who began their carrier in the 1950s and 1960s would remember the – often determining – experiences they gathered in the collections of the museum.

In the beginning of the 1980s, for a period of two years, I spent hours in the museum on Friday afternoons with artist Miklós Erdély and the members of the Indigo Group. Erdély himself incited me to accomplish this task. I have known the participants to this new series of interviews for decades, and I have already heard a few of their recollections. Lacking any possibility to travel abroad and visit international exhibitions, deprived of new art books and albums, they went to the Museum of Fine Arts to study.

On February 17, 2013, the day the Cézanne and the Past exhibition closed its doors, I decided to start this series of interviews. The personal recollections of these artists constitute an important part of the historiography of the Museum of Fine Arts. I first started with the painters who participated to the series of cabinet exhibitions organised by the Department of Art after 1800 in the past few years (Keserü, Jovánovics, Lakner). Many other discussions will follow.

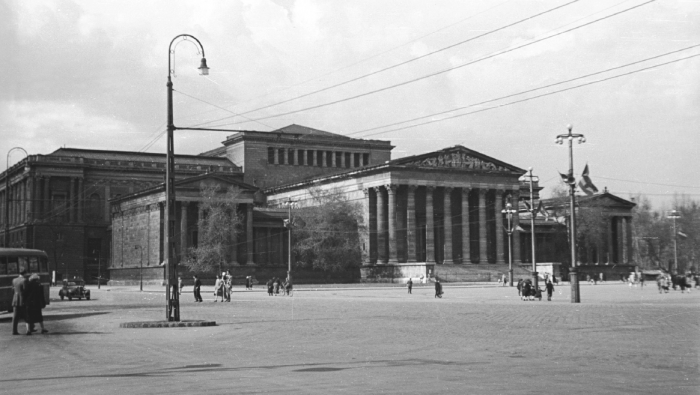

The Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest in 1953 © FORTEPAN © Gyula Nagy

Judit Geskó © photo: Dénes Józsa

Geskó Judit: How did you start your artistic studies?

Ilona Keserü Ilona: I moved to Budapest at the age of 17 and entered the vocational school for the arts, that was called earlier Lyceum of Fine Arts, and later became the High School for Art and Applied Arts. I completed the two last years of the program after having passed an equivalency exam. Before that, from 1945, I went to high school in Pécs, and in addition to secondary school I became the pupil of the painter Ferenc Martyn.

A woman, who was also a friend of my parents, brought Martyn with her on one of her visits. Aunt Bella had already seen my drawings, and she knew that I was making drawings all the time, that my need for sketchbooks could never be satisfied, and that I even drew on toilet paper before we used it. (I have other anecdotes of the kind: in 1944, by the end of the war, we were in Rábatamási, in the house of my grandparents (the Jászais). As the frontline was approaching, German troops fled and left their supplies behind them, which were stored in the village shop. With other children and villagers, we invaded the shop that was right in front of our house across the main street. I seized several kilograms of white A4 size glossy cardboard and a box of pencils. To be honest, the paper (one part of it was covered with columns, the other was completely white) was so glossy and so slippery that I could hardly draw anything on it. But still, it remained valuable loot). In short, for as long as anybody can remember, I was always drawing.

Our common work with Martyn started in Pécs at the turn of 1945/46, after he had a look at my drawings. Although they dealt with imaginary, mainly undefined themes, they were for the most part large compositions representing several figures, covering the whole surface of the sheet of paper. He took me as a pupil and told me that he would give me drawing exercises and that I should show him the results once every two weeks. He lived in the so-called “Deutsch” house, facing the synagogue opposite the square; there was a statue of Kossuth in front of it. At that time, his studio was set up in one of the rooms on the first floor of the house, but after a while it was moved next to the courtyard of the building, in a place that used to be the workshop of an artisan. It had huge mullioned windows. Later, when his wife Klára (a survivor of concentration camp) came back, they moved together in an apartment in Toldi Street, so afterwards I brought my drawings there. Klára was a pianist and piano teacher.

Ferenc Martyn also advised me to enter the Free Artistic High School of Pécs that he founded with a few colleagues. Today, this would be called an evening school or a free school. It was set up on the top floor of a house at 2, Perczel Street in Pécs. In the attic, there was a classical, Parisian-like photo studio covered by an inclined glass roof. It was probably nationalised in 1947 and it became a free school afterwards, shortly before I enrolled. We went there in the afternoon, after school or working hours. This meant that the place was heated, that there were models, artistic supervision, and Martyn also made corrections to our work. This school was mostly frequented by young people from different backgrounds who came there to draw, paint, and sculpt. There were railwaymen and foundry workers as well as housewives and students like me. Some of our works were selected to be shown at an art and craft exhibition for young artists held at the National Salon in Budapest. Thus, still a high school student, I exhibited a drawing entitled Landscape at the National Salon in June 1950. Afterwards, the organisers invited me to enroll for an equivalency exam that would allow me to join the Vocational High School for the Arts in Török Pál Street in Budapest. Viktor Kalló, a locksmith apprentice, was also invited to register for an exam to enter the College of Fine Arts. Gyula Buvári, who emigrated to Sweden in 1956 was also invited to join the vocational school. So, during the summer I passed an entrance examination for the two last years of high school in Pest. All of this was part of a nationwide campaign, searching for new talents.

Ilona Keserü © photo: Szesztay Csanád

And where did you live?

On the days of the exam, I lived with the friends of my parents in Reáltanoda Street. Having succeeded in the equivalency exam, I entered high school and, considering that I was not from Budapest, I was also granted a place at the school’s dormitory in Vendel Street. Later, after 1952, I lived at the dormitory of the College of Fine Arts Art on Herman Ottó Road, then on Stefánia Road and in different flats I rented.

Éva Hárs, who wrote a monograph on Martyn didn’t know about the studio in Deutsch house on the marketplace, maybe he used it only for a short time. But this studio is very important for me, as it was the place where I first discovered some spheres of art and of the human spirit that were unknown to me earlier, and where some essential conversations about my own work took place. The works Martyn made at that time went beyond the spatial and temporal limits of memory.

One day, I made a drawing of the square from the window of the studio. Another time, Martyn was still busy when I arrived and he told me to make a drawing until he was ready. He had a big seashell, one of a kind I had never seen before, he put it for me on a stool on the gallery opening to the courtyard and told me to draw it. This is very important as many believe that Ferenc Martyn, an abstract painter who had just come back from Paris, would teach me and his other young pupils how to make abstract paintings, but this is a childish thought. Martyn taught us how a painter or draughtsman can, through thorough observation and detailed drawing, get in touch, almost become one with a small part of the world. This is essential, today many artists cannot even imagine how important it is to learn all this.

I was struck by the viewpoint you mentioned: a fragment of reality grasped within the frame of a window. Many artists represented this experience in the 19th and 20th century. Was it an instinctive choice?

I don’t remember. But I still have the drawing. He probably pushed me in that direction, but maybe it was my own decision. One of the possible, great, traditional goals for an artist is to draw what he sees. He creates a vision, using his eyes, the skill of his hand and other aspects of his knowledge, activating the connections between the eye, the hand, and the brain. My drawing was still childlike and it showed that I obviously didn’t master perspective yet, but I went through a thorough artistic education in high school and college, where perspective was a course in itself. There, we also analysed perspective as a discipline, and wondered about the new role the artist confronted with the grasp of space could endorse.

It is very important that Martyn completely considered me as a colleague, an equal. Although he didn’t have children, and therefore couldn’t follow the path of a young being getting in touch with the world, he knew, he anticipated everything that was ahead of me. This was fantastic, at the age of 15 or 16 I wrote in a diary I don’t have anymore that I looked at and dealt with everything all the time as an artist. I already knew that about myself. Obviously, I had some reference points. Aside from my “civilian” classmates, I had around 30-40 cousins that I used to meet, with whom I spent the summer and holidays. I drew many of them. I still have these drawing and it’s interesting to see how the faces change over the years.

The discussions on my drawing were very far reaching. The fact that I was not yet able to see this or that masterpiece in different points, museums of the world was not an obstacle. He spoke about things just the way he thought about them. Once, I realised that he had set time bombs in my future, that would come to my mind and explode 15 or 30 years later, for example like the first time I saw a sculpture by Francesco Laurana in Florence. He talked about Francesco Laurana and made a small sketch, or he spoke about Pedro Sánchez, whom I soon discovered in one of the small cabinets of the Museum of Fine Arts, when I started frequenting the collections.

György Kovásznai, Ilona Keserü and János Neufeld (Major) on May 1st, 1952. Photograph taken by Irén Kresz (fellow student from the photography class)

Sorry, I am very curious to know how he showed you Laurana’s sculpture. It was a key-motif for Cézanne too, that is why I find it so interesting.

I thought about it a lot later, because I can’t see any connection between Francesco Laurana and modern times.

Yet there are connections, as his sculptures are constructed with basic geometrical forms. Two or three years ago, I visited an exhibition of Renaissance busts in Berlin, where several works by Laurana were on display. When I entered the room where his works were exhibited, and then went on, the difference between his vision and that of his contemporaries was palpable. He is a key-figure for modernity, not only for Cézanne. Even if this connection seems rather loose, Ferenc Martyn has some links with late 19th century, early 20th century French art, so I understand why he passed this on to you. If he mentioned him as one of the most important artists, we can be sure that he saw what isolated Laurana from his contemporaries.

I probably considered that, among other Renaissance artists, he liked Laurana very much for some reason. When I finally saw original works by Laurana, I noticed that he used very simple forms, very soft forms. He lacks all formal overstatement for me. This connection was later confirmed by the fact that it is mostly in Martyn’s drawings of heads that I see the subtle formal transitions that are also present in Francesco Laurana’s sculptures. There must have been a reason for me to see it that way.

Ferenc Martyn: Spatial Construction, 1946, painted wood, 60 cm. Pécs, JPM Modern Hungarian Gallery © photo: István Füzi

If you consider it soft – let’s use this word again – then Brancusi’s heads are soft, too. The surface of the marble seems to be covered in silk, but works by both Laurana and Brancusi are bursting of tension from the inside. In my opinion, this softness appears only on the surface. From this point of view, Laurana is a pictorial sculptor, therefore he could appeal to Martyn as a painter, and to Cézanne too.

Yes, but in my opinion this formal softness and the somewhat exaggerated beauty of the realisation correspond to a particular graphic style of Martyn. I had such a feeling as a teenager, but I never put it in words like this. Now that we talk about it: I felt that Martyn generalised things a little bit. So every drawing by Martyn is a Martyn drawing.

Of course.

And maybe that wasn’t very interesting to me. Probably because something was already decided at that time. That all of my work will not necessarily be executed under total conscious control.

You see, the net of small lines that he used in his drawings, covering whole surfaces, was always the same. This softness and the subtle formal transitions appear mostly in his drawings, but here I’m comparing specific portraits by Laurana with particular works by Martyn. Of course, he had other kinds of works. And I don’t think only about the series of drawings inspired by war entitled The Monsters of Fascism. He also made works, paintings and drawings that didn’t refer to a specific theme, but which were very strong, full of energy; there was some kind of universal quality about them.

Francesco Laurana: Female bust (Ideal Portrait of Laura?), circa 1490, marble, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna source: Wikimedia Commons

Did he show you any reproductions? Works by Laurana or Sánchez?

I don’t remember. Maybe he had a few…

But did you have an image of Sánchez’ work in your mind?

No, I didn’t. I only knew that he was an early Spanish painter. My task was to look for it. I found this small Sánchez painting in one of the cabinets of the Gallery when I was still a high school student and I was very pleased by it. The Old Masters’ Gallery of the Museum of Fine Arts was amazing! The early painting by Velázquez… The Peasants’ Lunch.

That bodegón, that still life.

Interestingly, we knew that this museum was the centre of the world, even though we didn’t know the others. The masterpieces that were kept there connected us with the rest of the world. Going to the museum was a deadly serious thing for us. I mean that we were very determined, and that it was in our blood. I refer here to some colleagues, some of my classmates studying painting at the art school, the most talented ones, with whom we founded a club. György Kovásznai, János Major (Neufeld) and I were the members of that club, but József Bartl from the painting class also belonged to it. Outstanding ambition and talent already showed when we were 17 or 18 years old, on sketches and drafts for the paintings we made at school. (I even won the school’s drawing contest the year of the final exam). This is a wonderful period in life anyway! But let’s get back to our main subject: among the museums in Budapest, the Municipal Gallery was also very important to me.

Pedro Sánchez de Castro: The Entombment, second half of the 15th century, tempera on wood, 82 × 90 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest source: Wikimedia Commons

The collection is now kept at the Kiscelli Museum.

At that time, in the 1950s, it was exhibited in the Károlyi Palace, which was close to our school in Török Pál Street, and it was there that I saw for the first time a large painting by Munkácsy, a version of Christ before Pilate that gave me a tremendous shock. It’s important for me to emphasize this, because by that time what had become natural and familiar to me in the realm of painting was the world, the wonderful, lively experience of abstract painting embodied by Martyn. But it was there that I saw for the first time such an enormous canvas in a museum: a dramatic, realist and classical, so-to-speak Grand Guignol composition. In any case, the huge painting seemed extremely complex and complicated to me, both in terms of genre and technique. It was completely different from the illustrative altarpieces and frescoes that I had seen hanging up on the walls of the cathedral and churches of Pécs, for example.

It was there, among the paintings, that we agreed with my friends and colleagues that the best would be to enter the class of László Bencze in college, because some of the peasant women he painted recently in the village of Dudar were also exhibited there. They reminded us of Van Gogh, although we knew his work only from books, but the library of the Museum of Fine Arts was already a very important place to us. It was a little bit later, in the following one or two years that we spent more time at the library, because we couldn’t have access to books on modern art anywhere else. And they didn’t teach us art history in a way that would let us discover these masters. All we knew was what we could see in the Museum, in the Old Masters’ Gallery and in the rooms of modern art. By “modern”, I mean the paintings of Manet, Monet, Gauguin, and Cézanne that we went to see as if we were coming on pilgrimage. I know that most of us remember the essential role of Cézanne’s Buffet among these early memories; they have mentioned it in interviews, in their own writings. But back then these were not memories; we were standing in front of the painting, wondering how he painted the top of the biscuits, the hues and values used to paint the powder sugar dusted on the rounded surface, what colours he mixed. So we were looking for the deepest and most indecipherable secrets of the craft and we found them. This was worth a lot, the visits and that we spoke of all this between us, as friends and allies in art, and that we pointed at the details of the painting, while we knew what the others were doing when they were painting a still life in school. This added a complexity to the practical side of our studies that… I couldn’t wish for anything more perfect.

So you basically “dissected” the only Cézanne painting in Hungary. You wanted to learn everything you could from it. From this point of view, there is probably no difference between the young artist visiting a big exhibition today, connecting with the works, and your earlier experience. So it’s not sure whether a huge exhibition brings more to a student of our day than what you saw during your years in college in this place of pilgrimage, the small room where the Cézanne painting used to hang.

That’s interesting. Because I maintain that I got everything I needed in my youth. Or do you think that anything more is necessary?

Paul Cézanne: Buffet, 1877, oil on canvas, 65,5 × 81 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest photo: Csanád Szesztay

No.

On the other hand, I also claim that I have been free all my life. But the question is: what do you expect? In the end, for those who dedicate themselves to art, freedom is the starting point. Without it, it is just impossible… If someone gets in the way of your projects when you don’t know yet exactly what they are, when you are just feeling the urge and the energy, the will to start something that you cannot define yet. If someone interferes with that… I was incredibly lucky to be born a woman. At that time in the Hungarian art world, no one paid attention to women and their work. They just ignored them. I could do anything, and that’s what I did! I don’t know how this works nowadays.

Well, it is still not easy today, but I think that our way of seeing things changes every 25 years. Thus, in 2030 your works will be apprehended very differently than they are now, and they will be seen in another way in 2060. The great masters of the 19th century have been reevaluated at least three times since I have started studying them forty years ago. Their sources, their originality, their influence. This discussion is thought-provoking because you unfold some of the basic steps you took as a young artist, including the relationship you built with the museum, and this testimony resonates with other hidden elements of your oeuvre.

It’s interesting that, after these early years of school study, I have always prefered to spend my time in museums alone. In fact, even if I didn’t go there alone, I went my own separate way right after we entered the building. And we set up a meeting or, after a while, I went to find the people who came with me. On one hand, I didn’t want to waste my time, on the other hand, I was very annoyed to imagine the other person’s vision, what he was seeing. But I had a lot to do among the paintings, I looked at the works of masters with whom I had been familiar for a while from the perspective of my own work as a painter, or I found myself some new predecessors amidst stormy emotions. I have a very important memory. We went quite regularly to London with László Vidovsky from the eighties onwards, together and separately. In the course of these many years, even decades, the National Gallery became a very important and deeply intimate place for me as an artist. When our daughter was four or five years old, we went to Trafalgar Square together. But Emma did not want to come to the museum with us. So what we did is that one of us stayed outside with her, walking, looking at fountains, buses, birds, people, while the other went to visit the museum, then we switched. And everywhere in the world, museums became the most personal, the most intimate places for me.

Diego Velázquez: Tavern Scene, c. 1618–19, oil on canvas, 96 × 112 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest photo: Csanád Szesztay

For you, is the Museum of Fine Arts primarily about the Old Masters’ Gallery, or do the huge exhibitions organised here in the last ten years also mean something to you? Or did you consider them as a kind of repetition of things you had already seen? Did you come out of respect for the great artists? Did you visit the Van Gogh, Cézanne, or Caravaggio exhibitions to verify something?

Judit, I was very proud that such huge exhibitions could be organised in Hungary; that is why I came.

So this was a social event for you?

No! I came deeply moved, proud, as a patriot!

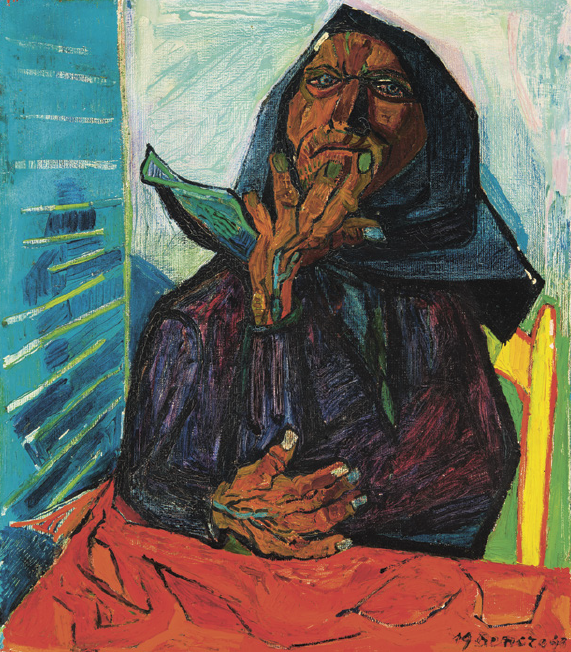

László Bencze: Old Woman, 1948, oil on canvas, 76,5 × 66 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest – Hungarian National Gallery photo: Gellért Áment

As a patriot, yes…

Because it was here, because it could be done. In a sense, I came out of respect for those who pushed through, who made all of this possible. And because you must celebrate the fact that the World is one and only Space. Because in our youth, aside from the museum, we missed the opportunity to see the world so much, we couldn’t travel in the 50s. It doesn’t matter now that we had access to books, albums published by Skira for example. I realised very soon that you can only relate to a work when you are in the same physical space, it is the only way you can actually see it. Only in such circumstances you are able to establish some kind of interaction with it. This way, the work can enter your mind and start operating in there.

It was in 1959 that I went abroad for the first time, to Poland. I was shocked to see that, in 1959, the galleries in the streets of Warsaw were exhibiting abstract and surrealist works; that it was possible to enter these galleries, and that museums also collected modern art. I still have a little book with paintings by Jarema, but I also saw a Kantor exhibition in Warsaw, while their northern gothic style of architecture also amazed me. The biggest, most incredible thing was that, on the way home, I had the opportunity to see original works by Braque and Picasso in Prague… In Prague! They had the same political system as ours. What did our leaders do here in Hungary? What did they do?

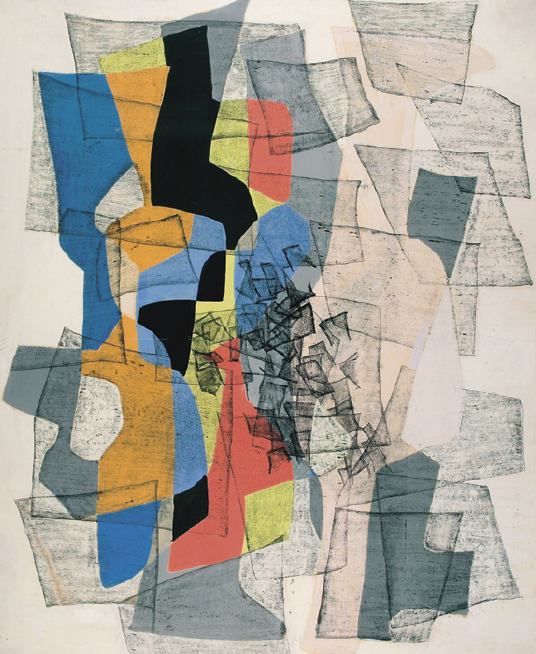

Maria Jarema: Breakthrough 6, 1956, tempera-monotype, cardboard, canvas, 105 × 85 cm

Those works were acquired by the Prague Museum before the World War.

But they showed them, exhibited them as if it were a natural gesture! And the younger ones followed this path. How many lies did we have to endure! They told us that it was impossible to do anything here, that we couldn’t invite anybody, that we couldn’t bring anything in. I blame them so much… but I cannot say names. Because I blame many of my colleagues among the older artists, who contributed to the closing of frontiers, of spiritual borders… Because of their own previous failures, of their misery, or who knows what reasons!

For younger generations, it’s an elemental freedom to come to the museum, to buy a ticket and to visit an exhibition that – to put it roughly – was made for them. I am younger than you, but in the 1970s, two exhibitions that I saw in the West, one Klee exhibition in Bern and one on Cézanne in Paris, had such a deep effect on me that I ran out of the show to catch some air. I could get back there only after half an hour or an hour, because I was stunned, shocked that I couldn’t see such things before.

That’s interesting because I was luckier than you, then. I knew about these things. I had small black and white reproductions of works by Klee, also a photograph of him, I don’t know how I got them. There were tacked on the wall of my flat, God knows where I found them.

Well, I knew about them, but I had not seen any original works before.

I have a similar story with Frank Stella. I went to Western Europe for the first time in 1970 (I don’t count Italy here, where I spent one year in 1962-1963). In Amsterdam, there was a Frank Stella exhibition. I entered, happy and unsuspecting, and I immediately saw on the left a very colourful composition of a surface of 8 or 10 square meters… and I just sat down on the ground. I was leaning against a wall and I fell. I couldn’t stand on my feet. To put it differently, I collapsed, but I had something to support me. Because of the dimensions, and because of the overwhelming forces conveyed by these dimensions, of the incredible shock induced by colours that you talked about. I mentioned Munkácsy earlier. This is a totally different thing, but huge dimensions can have a tremendous effect on people, not only spiritually, but physically, too. Here, I think about a complex reaction, human perception itself, that starts from one’s skin and gets into the brain, and even deeper, through the optic nerve. The first painting that provoked such a strong physical reaction in me was Munkácsy’s Christ before Pilate, the second one was Frank Stella’s painting and the third was the Danae kept in Saint Petersburg, which I saw in 1973. That time, I cried. But it was not the impact of the size. My tears were dropping, slowly.

I got so frustrated when I went to Philadelphia in June. In front of the new building of the Barnes Foundation, there is a wonderful sculpture by Ellsworth Kelly, about six-eight meters high, and I wondered why we cannot have such pure, simple public statues in Budapest. Why do we have to look at obsolete statues on the main squares of Budapest, from the 19th century, from the interwar period, from the 60s, 70s, 80s (like you, I prefer not to mention any names), instead of having relevant works by available European artists, works that elevate people.

We too, are available. Judit, I dare say quite egotistically that I have several completed plans for monumental, colourful spatial constructions that were prepared decades ago for different architectural environments in Budapest and Pécs. I have shown them to many architects and art historians, but nothing happened.

Yes. Let’s make that public now.

Actually Gábor Gulyás exhibited one of them, the Large Colour-Shifting Tangle made of painted titanium alloy at the What is Hungarian? exhibition organised by the Kunsthalle in Budapest. This work was also on display in Debrecen during my exhibition Forest of Images, it was suspended in the glass tower of the MODEM, so that everyone could see it from outside.

Ilona Keserü Ilona: Mandarin Square, 1990, oil, enamel, canvas, 150 × 150 cm

It’s such a non-sense that the Hungarian art world came out against the wonderful statue project made by János Megyik in connection with the extension of the Museum of Fine Arts, planned on a corner of Heroes Square, and attacked so hardly the idea of the “profanation” of Heroes Square and its surroundings with such a modern form.

Probably, there are similar debates in other places of the world. On the other hand, in other countries, decision makers do not care about them. Besides, the ones who protested probably only needed to express an instinctive response, to cry out their opinion. Maybe after a good decision, even on the next day, they would have been happy about the fact that what they wanted didn’t happen, that they didn’t manage to impede the realisation of something unusual, perhaps even of something phenomenal. Here in Hungary, the greatest problem is that people have been totally repressed from free, original thinking in the last 50 or 60 years, and that for this reason many of the changes in the urban environment that have already taken place in the western world couldn’t happen. Elsewhere, this process was completed in the public space 40-50 years ago, and just goes on today.

For this reason, I would like to compliment our general public that learned how to see in only ten years. It’s unbelievable to see how much they learned, following their own determination since 2003. Here, I’m not talking about older, cultured generations that had already followed this path, but about younger ones, to whom I listen to when I am walking around. One question: do young collectors buy your paintings?

No. Very young people don’t buy them. My new collectors are over 50 years old.

They don’t have the opportunity, I suppose.

No, younger generations are not interested in what I do; they have their own culture that honestly doesn’t give a damn about what we achieved. With my generation, something will end in art. Maybe all generations say that, and to a certain extent, it is true for all generations, but this is something global. Nevertheless, young children love my paintings, they can use their imagination to appreciate, to “use” my paintings, so to speak. To get back to the Museum of Fine Arts, I just want to say that The Ladies in the Dining Room by Toulouse-Lautrec, with its pinks and purples, was as important from the point of view of my experimentations with combinations of colour as… I don’t know…

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: The Ladies in the Dining Room, 1893–95, oil on cardboard, 60,2 × 80,7 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

The painting by Cézanne we examined earlier?

Yes, both were equally important.

But not only for the pinks!

Not only for the pinks, but for my generation, people born around 1933-1934, this painting was known under its Russian title, O jetyi dami, from the bilingual labels that were used in the museum in the 50s. We studied Russian for eight years, but couldn’t actually learn the language. I regret that now, nevertheless this Russian phrase didn’t correspond to anything that was visible on the painting.

You told me once that Martyn gave you exercises when you were a teenager…

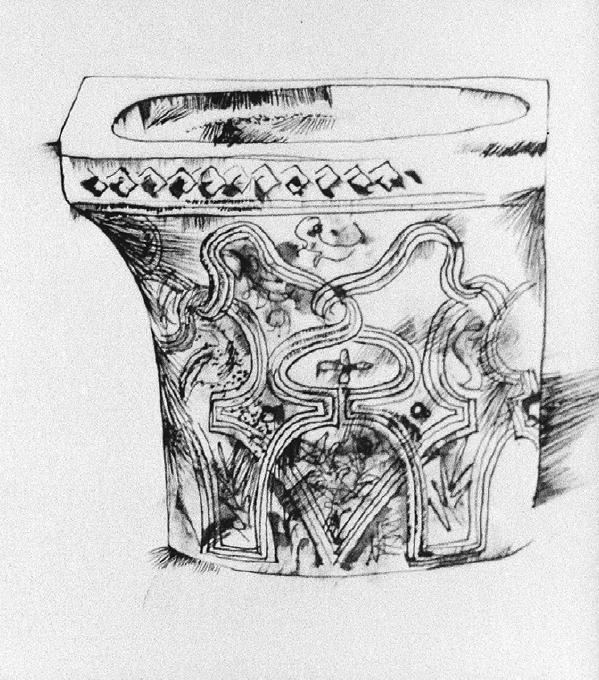

Yes, I had to find certain artists or works, for example among the old Italian and Spanish paintings of the Museum of Fine Arts. The other challenge was the Hopp Ferenc Museum of Asian Art, that I knew nothing of until he told me about it. He explained me where to find this museum with a funny name and told me to be sure to visit it when I spend more time in Pest. And I found a new world there. In Central Europe, what takes place beyond the Ural was considered, and is still often considered as if it were happening in another world. But I was keen on opening these closed doors, and later I always wanted to pass through such doors. Here I also speak about visits to the Musée de l’Homme and other Asiatic collections in Paris, to the temporary exhibitions of the Hopp Ferenc Museum or to their permanent displays, that were a bit less accessible. And I also include here my trip to Tokyo, where I was invited with other contemporary artists in 1985 for a “Hungarian week”. There, we visited museums, exhibitions, but we also had the opportunity to see Kabuki and No theatre. In 1988, together with a few Hungarian colleagues, I participated to the Artistic Olympics in Seoul where I exhibited my painting entitled Soft Movement. We spent a week there, the contemporary exhibition organised on this occasion, displayed in brand new, enormous buildings, was beyond imagination. One of the most surprising things I saw there is how their ancestral painting techniques could flourish in the works of young artists of the present day. These traditional india ink paintings are now made on paper sheets that have the dimensions of a wall. It’s amazing to see that they follow the path of their ancestors in such proportions, with such assurance. Back again to the Musée de l’Homme: there, I once drew, in fact I drew several times in my sketchbook a coloured square on black background, a Chinese embroidery the size of two palms. Throughout decades, each time I went there, I drew it again and again, I found it so interesting. Then in 1990, I made a painted, enlarged version of it, which measured 150×150 centimeters. I didn’t know what this embroidery was until I saw a similar piece at the Hopp Ferenc Museum in Budapest: originally, they were mandarin squares decorating the kimonos of Chinese officials. All this is part of my personal themes, and it started there, from these exercises and research I did in my youth. Today, they became an integral part of my artistic territory.

I have the feeling that subsequently Martyn also handed you over to Baudelaire and Manet. This means that the way of seeing that you just described in connection with the Musée de l’Homme and your trips to Asia clearly appeared when, in front or Baudelaire’s Mistress by Manet, you said that this museum and the tradition that you brought with you from Pécs made you understand very soon that what is important is the presence of a universal quality. What is important is what Thomas Mann, the great French poets, the greatest painters stood for. You can consider yourself lucky, because you always had a base that could elevate you, and this included the Museum of Fine Arts, that you discovered in your youth. Did I understand you correctly?

Yes, I had very strong supports. There is another thing I would like to say, although I’m not sure if I should point this out very often in my life, but there is a bloodline in our family that goes back to the famous Hungarian actress Mari Jászai. Her figure, her amazing talent as a tragedian, her career had a profound influence on me through the members of my family who had known her during her life. Thanks to her memory, which was kept very much alive, my parents accepted my wish to become a painter as if it were a natural thing, even when I was a little girl. It was already clear when I was ten. But no one was surprised, even though I was a girl, they saw it as a banal thing, like when someone wants to become a doctor or an engineer. I am sure that this is due to the fact that there had been, not so far back in time, a woman who became such a great, uncompromising female figure in the world of arts. (She was the sister of my grandfather, and died in Budapest in 1926). Especially when I was young, her memory, fondly preserved in my family, helped me a lot. So did the legends about her and the critical judgment that was of course also present in society: all this enhanced her greatness in my mind, and she became a model whose personal integrity, whose strength was irrefutable.

Édouard Manet: Lady with a Fan, 1862, oil on canvas, 89,5 × 113 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest photo: Csanád Szesztay

A modern role-model?

Maybe a possible range of what could be achieved. Only photographs remain of her stage apparitions, we will soon see the fragment of a film that was restored by a Dutch team, the only film left where she can be seen acting, moving in space. Maybe this is important because I wanted to be a model myself, to become a model in one way or another. This will only happen after the changes that are bound to occur in the near future, I mean when my work will become part of tradition. But the fact that such a model exists spares a lost of time and energy for people. Besides, these models remain valid, thus it is enough to point at them and many things become clear at that very moment: “Oh yes, there already was something like this, so the possibility exists, therefore it is feasible.”

She did the job for several generations to come. I feel the same way toward Simon Meller, Teréz Gerszi, János György Szilágyi, who achieved their work in the museum, and who made it so much easier for me. I knew who to think about when I was facing an unsolvable problem, I could wonder what they would do in my place. And one of them always helped me.

Thinking back of the time when I came to Budapest, it was such a huge change in itself that, aside from my studies (and of course, the discovery of museums was part of them), it took me years to learn to get around in Budapest as a metropolis, because this is what is was, undeniably. Whatever you think of the 1950s – we can speak about what happened in Budapest around 1950 – the old Budapest was still untouched from the point of view of culture, especially in the field of museums and even maybe the musical world. Despite the miserable dormitories, there were great possibilities for me in the city. I went to concerts, to the Opera, I went to listen to records four or five times a week. We completed our artistic studies according to our best knowledge, and besides this I kept my habit of drawing all the time. We went to Szentendre, taking the suburban train or a boat on the Danube, and there we fooled around, we looked at some wonderful works in museums, we had heated arguments, and we dismissed all the exhibits that we didn’t like.

I admired El Greco, Goya, Velázquez, Tintoretto, I found Pedro Sánchez in one of the cabinets. But at the same time, while I couldn’t find any work by Laurana here, I found something else. At the time, in the small cabinets, there were many paintings and many artists that I didn’t know about as a student, because they were not part of the official course. Moreover, besides the Museum of Fine Arts and the Christian Museum of Esztergom, there were no international artistic or historic collections in Hungary. We saw the private collection of modern art gathered by Iván Dévényi. Once, I was invited to the summer-house of an old wealthy family in Kisoroszi, where works by József Koszta, Adolf Fényes and other unattainable masters were hanging on the wall of the huge living room, which was on the first floor. I looked a lot at paintings by Károly Ferenczy, József Rippl-Rónai, Pál Szinyei Merse at the Municipal Gallery. And back again to the Museum of Fine Arts: I made drawings after the venetian pits in the great hall, I enjoyed very much Vilt’s self portrait that was exhibited for a while, and Meunier’s Docker. Slowly, intimate stories unfolded, I learned that Pietro Bembo had been portrayed both by Titian and Raphael. These wonderful, unchanging painted surfaces became family to me. Bellini, Breughel the Elder. I was in love with Sebastiano del Piombo’s Portrait of a Man.

Sebastiano del Piombo: Portrait of a Man, 1512–14, oil on wood, 115 × 94 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

So this is how it started. This is interesting.

And it felt natural to immediately discover these wonderful works for myself… Oh my God, it’s impossible to get used to this!

Now, Ilona sat down silently for a moment, because right in front of us one of her paintings is exhibited next to the paintings of Pissarro and Gauguin, and that made her say: “Oh my God, it’s impossible to get used to this!” To what? The good feeling, the surprise, the astonishment or maybe to the honour?

This is happiness!

Happiness?

Yes. Some kind of prideful, but simple, fulfilling feeling that I am at the right place. Several times in the last few years, I came to the conclusion that now I have become one with my paintings, even physically in some mysterious way.

Ilona Keserü Ilona: Venetian Fountain, 1964 oil, leaf-silver, India ink on canvas, 60 × 40 cm

I understand that. For a while I have felt, quite arrogantly, that “le musée, c’est moi”.

My painting is a part of me, a projection of my own self, a stage.

One of the shortcomings of the studies on Hungarian Neo-avant-garde of the 60s is that almost all of the monographs dealing with the artists of the movement do not mention the essential role the Museum of Fine Arts played in your lives. I became friends with the six or eight artists that I consider to be the most important of your generation, and I found out that, for all of you, the Museum of Arts became home in one way or another. That is why I decided that – starting with you – I would try to measure the place the Museum of Fine Arts holds in your memory and in the memory of the Neo-avant-garde. If the new buildings of the museum district are built, the permanent exhibition in the original building designed by Schickedanz will change drastically. Therefore, it’s a double task, a double duty, from your point of view also, to write down what this place brought to some of our greatest artists, what did the Old Masters’ Gallery and the Modern Gallery look like on the first floor of the Schickedanz building, which may change forever. So I would like to ask if you used to come here together.

We generally didn’t come here together in huge groups, but even later in college, it often happened that a few of us talked about it and we came together, in diversely composed groups. It is not a secret that our deepest admiration went to Cézanne’s Buffet. You said that this is rarely mentioned in monographs. But it is often discussed in interviews. I remember Sándor Juhász, who spoke about this in his last interview: the values he used in the painting, how he could paint with pure hues. This is how we grew up, with Cézanne.

Ilona Keserü Ilona: Stone Well, 1964, India ink on paper, 192 × 160 mm

And what do you think now that a hundred works by Cézanne are hanging on the walls of the Museum of Fine Arts? Is there an artist that has the same strength, the same relevance, who is bound to have the same importance for the future career of the students of today’s Budapest University of Fine Arts, as Cézanne did for you?

I don’t know exactly. I have the feeling that the students of today are more dispersed, and therefore they can’t concentrate on things as a whole. For us, each masterwork was incredibly interesting. The paintings of El Greco or that early work by Velázquez became part of me for life. For example, 15 years ago, I saw the latter at a Velázquez exhibition in Rome, together with another breakfast scene from Saint Petersburg that hung next to it on another wall. Well, I was so happy that I didn’t know what to do. It was mine, because I knew it so well from my visits here. This is what connects people. Within one generation of artists, and to all art lovers in history. This is why, when I became a professor at the University of Pécs, I told so many times to my students that art is an immense, ever-moving stream, a living club to which you can belong to as an artist if you are lucky enough. You can build a relationship freely with the other members, whether they are alive or not. Because the works are alive!

Yes. This is why it matters so much to me that some of my old friends, former members of the Indigo group said the following about the Cézanne exhibition: that they feel as if they were members of a club.

Of course! Young people who wish to become an artist should be incited to look at everything, and should not be discouraged when they find a path that promises to lead them to something great and hidden. Now that I’m here, all the same paintings are here in another arrangement, works by Bonnard and Maurice Denis… Afterwards, we were able to go to Paris, but that came a bit later in time. In the meanwhile, Paris, Rome and Florence came right here to us.

Ilona Keserü Ilona: Space per digitum, 2009, oil on canvas, 63 × 80 cm © photo: Gábor Horváth S.

In these rooms. Of course this happened because those who collected these 19th century works around 1900 and in the years that followed were real citizen of the world, who developed their taste in the best European collections from Rome to Paris, and who knew the Esterházy collection of drawings, paintings, and prints. They (not only the Museum of Fine Arts, but also the great private collections that were later dispersed) built this permanent collection of 19th century art knowing all the interrogations and paths that could be pursued, with the Collection of Old Masters as a starting point. Much later, my generation learned all this from the collaborators of the Department of Antiquities. In the 70s, János György Szilágyi, talking about the still ostracised modern, avant-garde art, showed us every day the connections between artefacts made three or four thousand years ago and contemporary or 20th century art. He showed us how archaic sculptures or vases and sarcophagi painted in geometric style were linked to the art of the 1910s and some currents of the 50s. That there are links between the drawing style of some ancient lekythoi and the art Toulouse-Lautrec (and Picasso).

This is very interesting, because for me there was something similar in the way Martyn taught me things, which made it so difficult for me to succeed at the College of Fine Arts in the 50s, when it advocated the doctrines of socialist realism, exclusively. I also would like to mention that in the 80s, when I taught drawing and painting at the art faculty at the University of Pécs, my students had to work on abstract compositions and on studies after nature almost at the same time, sometimes on the same day. So this is not some kind of linear mental development, a series of exercises that are built up on each other chronologically, but rather… How could I express this precisely?

Ars una – There is only one art.

And that you can turn to everything that was realized in art, anytime and anyway you want. I would like to mention another example that I wish to analyse more in depth sometime. During the last few years, I became more and more interested in the fact that some aspects of abstract, gestural painting already appear in late renaissance paintings, maybe even earlier. In many places they appear on the same pictorial surface with more traditional painting techniques. They used it for some details, for example to represent the veins of the marble. If you look at it closely, you see that painting is totally free, just like in Art Informel.

Judit Geskó, Ilona Keserü Ilona and Anna Zsófia Kovács photo: Csanád Szesztay

Also on architectural representations.

I noticed that for the first time not so long ago, it was astonishing. I saw a renaissance exhibition in Rome in 2001, which was meant to be a travelling show. It was exhibited on Via Nazionale and then travelled around the world, the next venue was Tokyo. There were some amazing paintings; many of them were unknown to me. Completely astonished, I stood before a 16th century painting showing the interior of a room, where the marble on the floor was rendered with free, “informel” stains. This appears in many places in several large altarpieces kept in the Old Masters’ Gallery, in architectural backgrounds, representations of walls and stairs. The interesting thing is that it brings these old paintings closer to the viewer of today, because they know this technique, this brushwork from the works of contemporary painters. Turning back again to the college years, the library of the Museum of Fine Arts was a real refuge. We frequented it often, especially in winter, because it was warm inside. I remember the large and heavy tables; maybe they are still here somewhere…

The library moved from the main building, but I brought one of these huge and heavy tables to the deposit of the Department of Art after 1800, and the chair you sat on earlier in my office also came from there, and belonged to the table.

Thank you. You know, we went to that desk to ask for huge albums and books where we studied and looked at things that were prohibited from the official courses of art history. I believe that Manet was the last painter that we were allowed to talk about in the 50s when I came to Budapest. Two years later, I passed my final exam in high school, then went to the Budapest College of Fine Arts, where we didn’t even get to Manet. We were not allowed to talk about anything that came later. I don’t know how our professors could swallow that, but somehow they did.

Were the collections of the Gallery the most important for you, being a great colourist? Did sculptures also grab your attention? What about the collections of Graeco-Roman or Egyptian antiquities?

For me as a future colourist, the picture Gallery was the most important. But during the 50s I used almost exclusively dirt colours. We had a look at everything, but I was not yet aware of the connections between distant eras. Maybe it became clearer when I was able to visit Pompei or Greece, but this came much later. It became obvious when I had the opportunity to share the same air as the statues. I can’t do anything with a reproduction, and that was already clear when I spent my days here among the paintings. You need to be in the same physical space as the work, it is the only there that you can actually see something.

Around 1950–52, it was above all in the picture gallery that you could get the best experience of how great artworks can go hand in hand with each other, for example an important piece of the Spanish collection and Baudelaire’s Mistress by Manet. Or Dutch landscapes and landscapes from Barbizon. Did this kind of continuity appeal to you? Considering that you are not an art historian, did you rather put aside the examination of these connections and concentrate on one work at a time?

I was rather attracted by works individually. I developed great intimate relationships with some of the paintings. I liked Baudelaire very much. I started learning French very early, when I was still in high school in Pécs, so I was able to read his poems in their original version. (I started studying Latin at the age of 10, and began French there, too. Latin was the base; I still remember the pages of the grammar book written by Birkás. If you used that book to study Latin, it was much easier to learn French or Italian.) In the 50s, you could buy French novels and poetry books in old second-hand bookshops in Budapest for almost nothing. I read Maupassant a lot, and I found translations of French poetry by the best Hungarian poets: Rimbaud, Verlaine – but Baudelaire… He was the darkest, the most mysterious of all. I looked up many things in their original language, and I know these poems in French, too. Somewhere in my head, I hear and murmur one of these phrases as if it were music, for example when I look at the Manet, Bonnard or Monet paintings. Pictorial language and poetic language are capable to connect with each other, even to merge. I had very personal relationships with some works; there were certain paintings I always went to see. With Jovánovich, we share an inclination for Sasseta. Sassetta’s small panel means a lot to me. I didn’t know that it was the case for him, too.

Yes, and it also the case for Megyik. We will get to Sassetta in a minute, but here, in front of the Manet, let’s speak about the structure of the skirt, the changing nuances of the whites and the Russian avant-garde of the 1910s. Of course, you didn’t know any original works by Malevitch around 1950–52, but did you hear about the White on white or about the Black Square?

I did not hear about them at the time, but, considering that Ferenc Martyn was a member of the Parisian Abstraction-Création group until 1939, his new masterworks made in Pécs around 1946 were among the best of the kind. I wouldn’t say that they were made before my eyes, because he never painted when someone else was around. But I saw these works in the making. Nevertheless, at the same time, he had a reproduction of the Miracle of Saint Mark next to his desk.

Let’s go to see the Sassetta. Here, was it the composition or the colours that had the greater effect on you?

I couldn’t tell. Now, I tend to make confusions between the period before my trip to Italy and the times that came later when I had already been there, and when this vision came to my mind when I was actually visiting a building in Italy. To me, it was a huge thing to travel to Italy for the first time in 1962–63 and to see a lot of places with some wonderful architecture. In retrospect, the pits of the past seem endless, there are of the deepest depth, so to speak. You see, there is something of Thomas Mann in this… Because you could read his books in the 50s. The fact that I discovered Proust at a very young age, that I had this intuition, is due to chance and I bought all the volumes of the first edition and got lost in it, but Thomas Mann was much more accessible. To return to Baudelaire’s mistress, it was an exciting thing in itself that you were allowed to say the word and that it refered to a well-known situation, to a woman, a vision, a social status. It showed something about the world, an attitude; it provided an insight into something that wasn’t familiar in Hungary at the time.

You see, that is what my question refered to, when we left my office and my tape recorder wasn’t turned on yet: was the Museum of Fine Arts only a source of aesthetic discovery, or was there a sociological, social aspect to your visits? It seems to me like there was.

Everything was here. I met with all sorts of interrogations here. There was a painting that used to be called