“What you see is what you get, reality doesn’t pretend to be anything else than what it is.”

Interview with Hans van der Meer

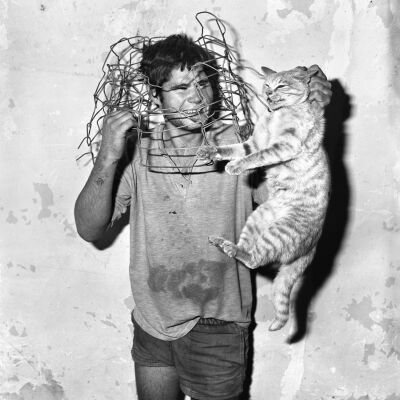

Hans van der Meer was born in 1955 in the Netherlands and is considered the most distinctive Dutch documentary photographer of his generation. On the occasion of his exhibition titled Minor mysteries on view until 23 december at the Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Center in Budapest we were also able to meet him – so we talked about the pictures he took in Budapest in the 1980s and the time he spent in Hungary, the relationship between photographs and words, his archive, and a tiny bit about football too.

What interested you in the Eastern bloc when you first came to Hungary in the eighties? As far as I know, you didn’t stay in Budapest, you left for Lake Balaton quite early.

We were curious to see how people lived here, that was the first reason why we came to Hungary in 1982. Me and my girlfriend at the time took the train to Vienna and then came by boat on the Danube. It was a very hot week in September so we stayed in Budapest for only a couple of days, then went to Balaton. I took a few photographs there – in Keszthely and Sopron – and when I saw them later in the darkroom I thought that the light was very striking. The images showed a different reality.

After having finished my technical studies in photography I worked for a couple of years – and occasionally worked for free. But then I thought: is this what I want to do? So then I made up my mind: in 1983 I applied to study at the Rijksakademie, where I was admitted in August 1983 to experiment and deepen my visual language. I was inspired by certain street photographers, but I felt I needed to find my language in photography.

Who inspired you?

The obvious generation before me: Henri Cartier-Bresson, André Kertész and Robert Doisneau. Cartier-Bresson went to Russia during the Cold War and showed the life of ordinary people. His images were published in Time magazine in 1955 – the same year when I was born. At that time it was quite radical.

You kept coming back to Hungary. Why?

In the early eighties there were huge demonstrations in The Netherlands against the nuclear rat race. In the second year of my studies at the Rijksakademie I phoned the Ministry of Culture to ask them: “What do I need to do if I want to work as a photographer in Hungary?” It turned out that there was a cultural exchange program and a short visit would be possible, courtesy of the Hungarian Ministry of Culture.

In May 1984 I was a guest of the Ministry of Hungary for two weeks being part of a cultural exchange program. But then I didn’t know if I could stay here longer – until they told me to feel free to stay and do what I wanted to do. Being here I never had the experience that they – meaning the government – were keeping an eye on me. Maybe they did. You never know. But I made some friends in Hungary.

The first reason for being in the country was to find out what I wanted to do with photography. I was attracted to the visuality of reality here. What you see is what you get, reality doesn’t pretend to be anything else than what it is. Soon I understood that what I saw was a part of Hungary’s history. But I have to tell you: I didn’t come here to leave my comment on the political situation or anything like that. I came here to study and I was mainly focusing on people’s body language in different situations. That experience became very decisive for my later work. But I can only see this looking back, I didn’t know it back then. We often see a lot of things, but we know nothing about the stories behind the visible. That is why for me photography is good to be able to raise questions.

What exactly inspired you about Eastern European culture?

I was influenced by the cinema and the writers but internationally also by people like Buster Keaton or Jacques Tati, in how they explored visual comedy. Also, films from the Czech Jiři Menzel and books from writer Bohumil Hrabal. I was also impressed by the sense of humor and what we call black humor. The way how people in the Eastern part of Europe were dealing with life inspired me. Life here was quite harsh at the time, people were stressed. A lot of young people wanted to leave the country, so there was a certain restless atmosphere amongst people.

First I came for two weeks, then I came for three months and then I kept coming back. I realized that if I want to make a decent job here I need more time. I needed to learn more about the country and learn the language a little bit. I had to make friends to understand the reality here and what I was looking at.

While in Hungary you experienced the period of the system change. What was your experience, and what changed?

I was here during the reburial of Imre Nagy in 1989. I was here when the first free election happened. There was an atmosphere of hope while a country needed to reinvent itself after huge problems. Outside Hungary, there was this capitalistic world and it made the already confusing times even more confusing for Hungary. People were confused, but they also had hope. But I only saw this from a distance so I can only give a general opinion about what happened.

Do you think this generally different aesthetics of Hungary has made it more liberating for you to create new photographs playfully? It influenced a lot of non-photographers in Hungary to take photos, too.

The Leletek a magyar fotográfia történetéből (Findings from the history of Hungarian photography) book created by Sándor Kardos and Gábor Szilágyi was published in 1983. In this book, there is no distinction between unknown photographers and known photographers. The authors selected a very powerful photography collection hence showing us what photography is good in. Photography is sometimes playful and sometimes images can turn out to be poor. But also, it's a very direct output from what people do with a camera. Even when they are not photographers. Kardos and Szilágyi showed us that the only thing art needs to do is to talk about the miraculous diversity of life, as Tolstoy said. And that the history of photography is not only written by artists and journalists, but by a lot more people.

While you were in Budapest you were wandering around town creating photographs. How did you spend a day when these photos were created? What was your method?

I would usually walk and take photographs for about four hours a day. I had a Leica camera, some rolls of 35 mm films in my pocket and just explored parts of the town. The Buda side was more difficult to take pictures of as there was a different atmosphere, so I do not have a lot of pictures from there. While being on the Pest side I found people in situations where I could isolate them a little bit from other people in the frame. I never really went to Váci street because it was too crowded to be able to do this. I liked the streets that were not empty but also not crowded. I needed that to be able to isolate the main focus of my picture in an almost theatrical way. It was quite an intuitive way of working, not always looking through the viewfinder. There were times when I just quickly released the shutter hoping that my camera would surprise me. Sometimes I had problems deciding which direction to walk when reaching a T-cross on the streets. I remember standing there thinking about what I could see and what I would miss if I went in the other direction.

Ten years later, when I started the amateur football series it was much easier to play with the unexpected, because I could shoot the game from a fixed spot and I knew it only lasted 90 minutes. The controlled part was the location that allowed me to frame a relevant backdrop. The out of control part were football situations in the foreground. But during the game, it was still somehow the same as in Budapest because unexpected things could happen.

During the days in Hungary, I was running towards something without being able to plan. And playing with photography meant that I pressed the button without even being aware of what it would generate for me. You can clearly see in my contact sheets how my method is trial and error. But there are a couple of dramatic photographs in my archive that I decided not to show because people are vulnerable when you photograph them in public without permission. It is my responsibility.

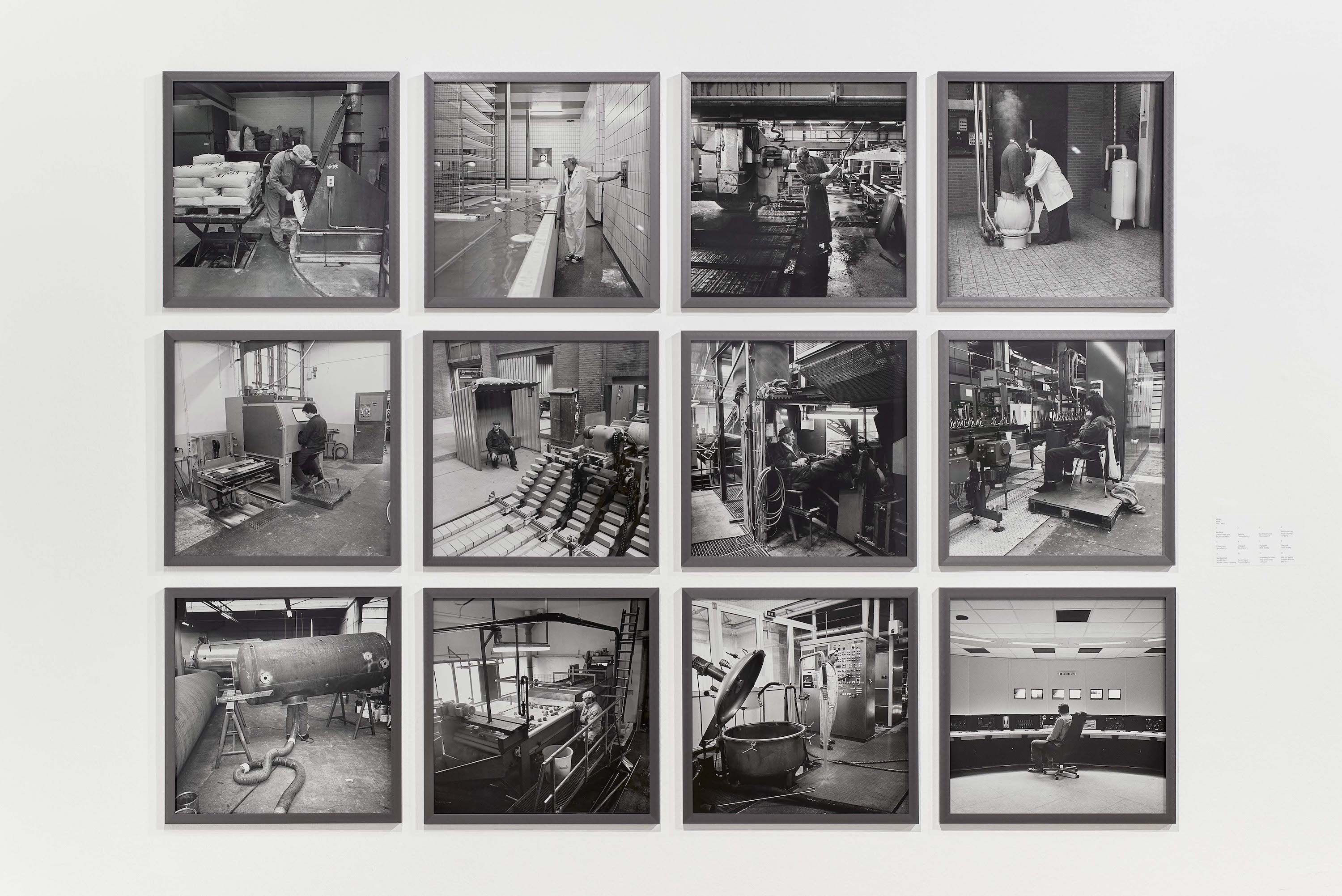

For the series titled Work, you were able to get the permission of the people who became subjects of your photographs. Was this experience entirely different?

The nature of the work had changed, labor became less physical. In factories due to automation more and more people are just sitting there in front of or next to the machines monitoring the process in a relaxed position on a chair. The machine is doing the work and they are there to act only if something goes bad.

When you come in with a camera they have the idea that they should express the fact that they are working. So they sit straight up. But their work is to control a situation. The machine is doing the work and they are there to act only if something goes bad. It was funny when these people realized I would take a picture of them working, but the picture will tell they are not working because they are sitting comfortably in their chairs. I had to convince them that the theme of my project was about that change, and had to ask them if they could lean backwards and sit comfortably again for the picture.

There is a certain dynamism and narrativity in every one of your images.

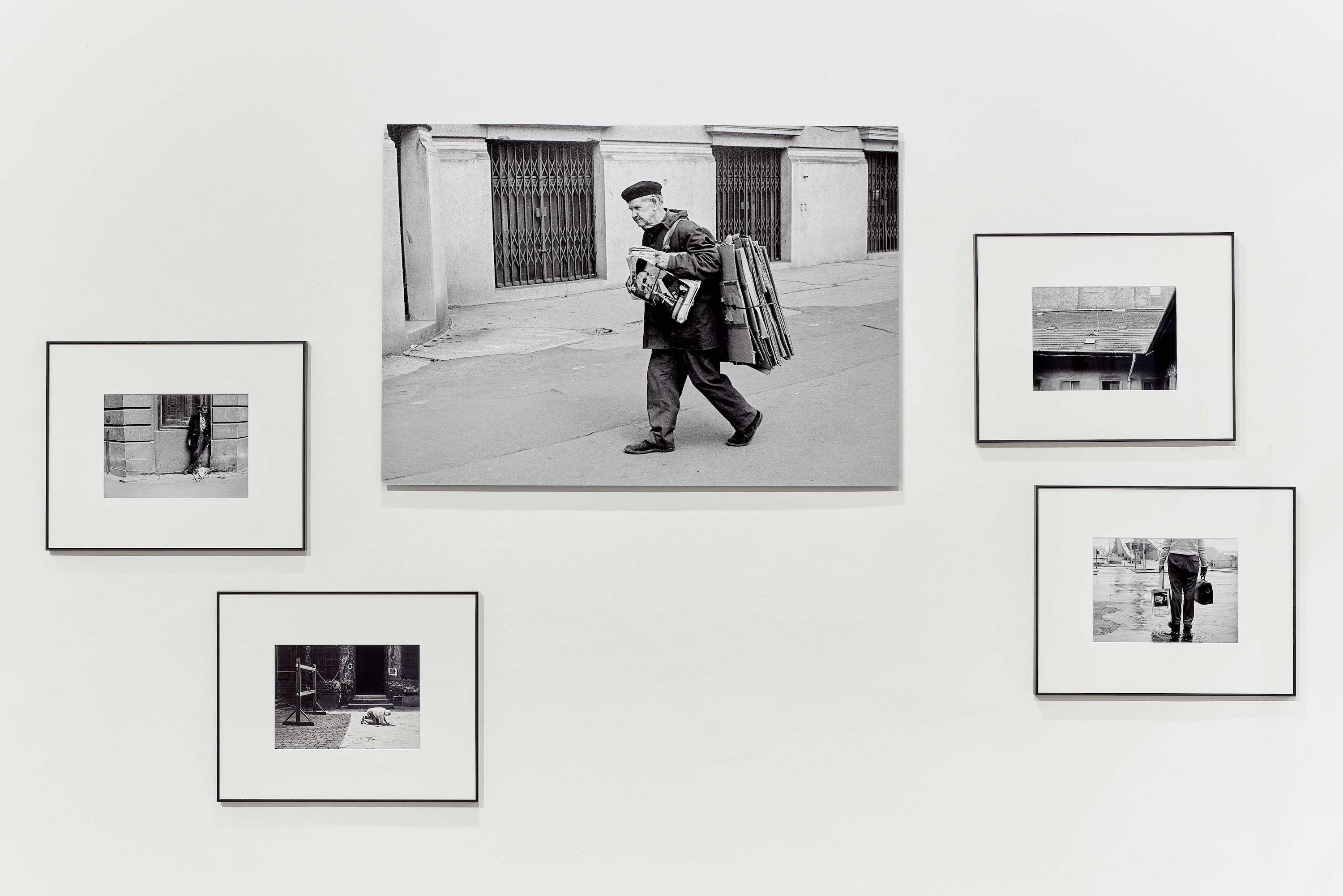

But that is the big question: what is the story? The photograph I took of an elderly person dragging some cartons behind them. Those were the kind of photographs that made me think: these people are not doing this for fun and in this sense, it was not easy to take these pictures. They are part of a bigger story, these people had to live on a small pension from the government and had to collect cartons to take them somewhere to get more money. The situation wasn’t funny, I could take photographs of it, but it was my responsibility to do it in a way not to make fun of them. I had to learn that. I had to put myself in a position of what I would feel if I was photographed in a situation like that – but without dramatizing it. It was a situation where there was a bigger story involved.

In the end my subject was not only the people but also the world around them. Budapest looked worn out in those days. Photography often describes in the unintended details in the backdrop how things have changed or disappeared.

You left your Budapest images enigmatic, no text guides the visitors. But later on, you started to give little clues in your texts – how did it evolve from no texts to using texts to help the visitors?

For the Work series, I wrote a foreword and I generally liked writing – I even wrote a lot of letters while I was in Hungary. Then in 2004, I got a call from NRC Handelsblad, a Dutch newspaper asking if I wanted to create a column on the back of their paper for one month. They asked me to go around in the countryside and produce a photograph and a text every day, for a month.

I found the tone quite easily because I already had the idea that the duo of picture and text should be a bit puzzling. In this series for the magazine – published later that year as a book called Achterland (Hinterland) – I looked at my own culture and the layout of the country for the first time and my question was: why does it look the way it does? I started to take photographs of things that raised questions about the story behind. When you isolate something from reality and put it in a museum or on a piece of paper it becomes a ready-made thing. Because it suddenly has a different context. Playing with the option of using text and images in that sense suited me so well because I was already on the track of doing things like that.

Were you ever afraid of the fact that writing short texts to your photographs can change those photographs into illustrations of that particular text?

This is a good question because in newspapers it's exactly how photography is used. Picture editors working for magazines and newspapers often ask: “look, this is the subject, search for some images for me”. For me, it’s the other way around. I would like to start with an image. When I was doing the project for NRC Handelsblad I chose the image first and it had to be strong. What I tried to reach was a fifty-fifty balance between the image and the text – so the image was just as important as the text.

I was wondering how you organize your archive.

The Budapest-based material’s archive is quite randomly done because it's a very random project in that sense. During that time, my private life and my photography were literally one field. And just after Budapest, I started new projects. I bought a six-by-six camera for the Work series, so at this point, I used a different camera for my work than I used in my private life. This means you do not see much of my private life in my archive afterwards.

But back in those Budapest days, I fell in love with a girl and I dated her for a while and we lived together. In these films, you see a lot of my private life. I didn't archive things well, because I would develop a lot of film per day and sometimes wouldn’t write dates on the developed materials. I never wrote down where the photographs had been taken. Sometimes you know it because you remember where it was. But quite often I have no idea where I was in Budapest while taking the pictures. My father was a bookkeeper and I am an administrative type of person, but I was not at that time.

Do you miss some of this data now?

It would be nice to have them. But it’s a bonus now that people can guess where the pictures could have been taken. Almost all the pictures from the Minor Mysteries series in Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Center are from Budapest except some. There are at least two from Miskolc. There is one from Szolnok because I did visit other towns sometimes. I visited Székesfehérvár, Békéscsaba and Debrecen too.

You mentioned that you made friends here.

I met Tibi who was working for Mafilm and television. Lajos was also a cameraman for television. Csaba is a good friend, he is in one of the pictures in this exhibition – he was the guy who picked me up from the airport when I arrived the first time. We had a small group of friends and they were into jazz music. We would go to the house of Baricz Katalin and hang out together. When I came to Hungary they organized meetings for me with Péter Korniss and with young photographers. And that was the first circle of people that I got to know here. And it was okay. I was in a small group of friends and it felt good.

It felt also familiar, people were reading the same books and listened to the same music. I had a vague idea about the life of people here, it is hard to imagine these days how that iron curtain divided Europe into two worlds. But I came to realize that I had a lot of similarities with the people I met here.

We have already touched on the topic of body language. Regarding the photographs taken in Budapest, you were interested in the streets that weren’t too crowded so you could focus on one figure or a group of people. Is it for the same reason why later on you decided to take photographs during amateur soccer games?

Well, it was a subject that was very generous to me. I started to do it because I know it very well. I am an amateur football player. Besides me liking the game it was also about the landscape, about the environment around me and the players. And then there was this acting of adult men when they are in pain on the field, which is so funny. It brought the element of body language into the project again. So it had a couple of things that gave me a lot of energy to explore the topic. And it felt so good to do something with a subject that is so familiar to many people all around the globe. When I showed the images to a few people I have to say not everybody understood them in the beginning. They thought my pictures of amateur football were amateur photographs. But shortly after the book Dutch Fields was published in 1998, it was picked up by the art world.

Later on, when I was working on the European fields series, the images became much more conceptual in terms of viewpoint and framing. Talking about football, you don't know what's happening in these pictures, but it triggers your imagination about what could have happened. And that is exactly why football is such a visual sport, but to understand these promising moments you need to show the space. And not only two players through a telephoto lens what sports photographers do.

Have you taken any photographs in Budapest this year?

I had been thinking about taking new pictures a couple of years ago, but I let it go. The city has changed and perhaps I could find similar situations, but I don’t want to.

When I went back to Amsterdam in 1986 I continued this kind of street photography for a while. But the result was so disappointing compared to my photos from Budapest. So I decided that I didn't want to continue with that kind of street photography. In later projects – like Amsterdam Traffic (1995) and The Netherlands – off the Shelf (2012) – I worked in a very different way. But my experience in Hungary, the questioning style and making use of body language has always been with me since then.

Edited by Róza Tekla Szilágyi

Hans van der Meer: Minor Mysteries

September 15, 2022 – December 23, 2022

Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Center, Budapest