“I don’t mean to impress”

Beatrix Szörényi talks to József Mélyi

Beatrix Szörényi graduated from the Intermedia Department of the Hungarian University of Fine Arts in 2006. The notion of straightforward pragmatism that brought her to Hungary—after living in Germany until she turned 20—is typical of her art as much of her attitude. Her art reaches back to a less complicated, less technological level, an approach that gives way to a more diverse set of feelings and meanings.

József Mélyi: Do you think in Hungarian or in German?

Beatrix Szörényi: When studying at the university, I couldn’t read or write in Hungarian. Now, I’ve been in Hungary for so long, I’ve lost track, so I don’t know, really. Furthermore, English is there, too; the language used by competitions and project descriptions. I’m constantly translating in several directions, which, occasionally, leaves me in a total linguistic chaos.

When did you arrive to Hungary?

Both my parents are from Hungary. My father left the country in 1956, my mother in the 1970s. They met in Germany, and I was born there, in Düsseldorf, in 1976. My father is an architect, my mother is a doctor. We had Hungarian friends to spend time with and we were speaking Hungarian at home as well; nevertheless, there were no serious expectations regarding the language toward me. In school I was using a mixed language, with Hungarian always present in the background, gradually becoming less alive. I spent two years at the university in Kassel, it was there where I came up with the idea of returning to Hungary, to gather my own authentic impression of the country.

You didn’t go to the University of Fine Arts straightaway.

No, first I applied to the video/animation program at the College of Arts and Craft. No matter how competent the technical education was—with teachers like János Szirtes, Géza M. Tóth, or Anita Sárosi—, after one year I realized that I want something else, that that was not my milieu. I wanted to be involved with fine art since the beginning; yet, you don’t apply to the University of Fine Arts at the age of 18, I thought. I was serious about that, and perhaps I was shy, too; even in Kassel, instead of studying at the Kunstakademie, I attended visual communication. But I was a museum guard during documenta X! That was the worst job, ever! Sitting was forbidden, and we were not allowed to talk to visitors, let we, naive little guards, said something stupid… Anyway, it was a defining experience to me; I got closer to contemporary art, and it played a significant role in my later decision. Nevertheless, after the first year at the College of Arts and Craft, I skipped the next, but didn’t do much; I attended Gabi Csoszó’s photo course for example, which was a further push toward fine arts. Back then, I saw two options ahead of me: studying graphic design at the academy in Vienna, or intermedia in Budapest. I was not accepted to Vienna, which was O.K., since I lacked the classical drawing skills, I recognized that in the meantime, too. This is how I ended up at the Intermedia Department of the Hungarian University of Fine Arts.

Still, most of your works are based on graphic art…

The lack of drawing skills was only a temporary problem, after a while I realized that it doesn’t matter, really. I’m entitled to do whatever I want and however I want to do it; if I face a difficulty, I can find a solution to it.

Does this easiness come from the Intermedia Department?

The Intermedia Department? I don’t think I know anybody who felt easy there. We had so much input—true, no one requested perfect drawings; the content, however, and presenting your work, were crucial. The bar was always higher than what you could reach at the moment.

Who made a big impression on you?

I’d be surprised if there was anyone who was not influenced by Tamás Szentjóby to a big extent; he was charismatic, he strongly identified with his ideals, it was impossible to ignore him. János Sugár is different in character, at first he is too much—he was often very hard on us. Yet, students were intrigued by both of them, by the sheer fact of meeting two authentic artists, with all their ambiguities.

Are there others who serve as points of measurement for you?

I was waiting for this question. I have a difficulty with specifying names—it constantly changes. Often someone doing something completely different than I am has the biggest impact on me, by doing something that makes me think.

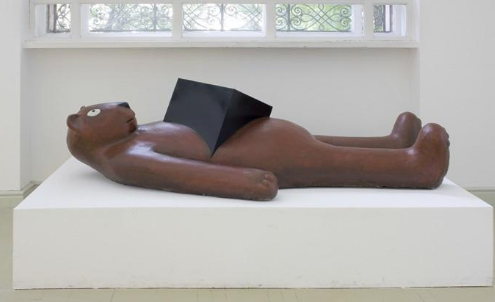

However, your works often have precedents from the history of art. Just to mention one, your huge Malevich object. Can this association be limited only to this very work?

There are recurring figures, indeed, returning from time to time; but because I’m always interested in them for a new reason. An exhibition in progress or I’m beginning to be involved with something new, and then, “suddenly,” I just face all those information and points of reference, like an album by Malevich or some text; and these just stack up. Eventually, they get closer and closer to each other, and by forming connections they compose something new, unexpected, a piece of art or an exhibition. People meditate on the same set of things all the time, but the way they exploit them changes according to how the situation varies.

What do you meditate on all the time?

It’s hard to escape clichés... I prefer to employ a sort of absurdity and irony in order to see and present things in a way that’s somewhat different from their original appearance. I’m highlighting and rotating things so that they can be seen from new perspectives. Recently I read Miklós Mészöly’s short story Jelentés öt egérről (A Report on Five Mice), in which I discovered a technique, an approach characteristic of my works as well. After an objective description of the mice’s behaviour, a couple of sentences infused with cynicism and criticism describe the way we relate toward them. I’m trying to show something similar: the absurdity of us being so confident in our judgments, our humaneness, our goodwill. It is this certainty that I want to challenge, I want to question its validity.

Instead of absurdity, perhaps, what initially comes to mind when looking at your works is that this challenging is always done to the same degree, its impact always remains to be minimal.

It could be; from this point of view my earlier works were like that, too. I think it was Sugár, who said the following, quite accurate comment about my works: when it comes to me, everything follows a human scale, not too big, not too small. Apart from a few exceptions, this does apply to all my works; to me, this seems to be the adequate dimension. I don’t mean to impress, usually...

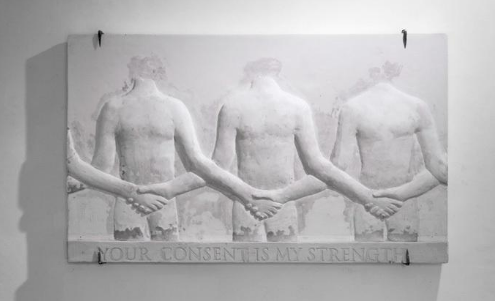

Your consent is my strength, 2008

Unlike István…

[István Csákány, partner of Beatrix Szörényi] Don’t say that, or he’ll be mad at me for undermining his practice… Obviously, the two of us are very different in several aspects. There are interesting overlaps, even in the issues we address, but not in the scale we use—resulting in numerous debates. István insists that I should work in a bigger scale, recruit assistants, build a team to help me with huge drawings. Which, I think, is completely unnecessary.

Do you wrestle a lot?

We do; we help each other a lot, but we wrestle and debate, too, that’s inevitable. Which can come in handy after a point, having the first critical viewer within reach. Unlike him, I’m flexible regarding the progress from the first idea to the final outcome, being adaptable is important to me. Others often work according to a strict conception or vision, I, on the other hand, am unsure if the artistic process can be thoroughly controlled. I’m deliberately trying to integrate the unexpected, I’m creating unclosed situations that allow factors either unintentional or seemingly difficult to place.

Do you remember how you imagined your future when you completed your studies?

Of course I do. It was around 2005 when the Studio (Studio of Young Artists’ Association) became our headquarters; István had his studio there, so did Tamás Kaszás, Miklós Mécs, and we were joined by Anikó Loránt, Miklós Surányi, and Judit Fischer. We all were friends, the work—and our life—was very intensive. We entered competitions together, we worked, partied, and exhibited together. This was how we made it through this awfully demanding period, full of questions like “Does anyone care about what we do?” or “How do we begin?,” and “How does this life work?” Looking back, this was a very intense period, with no clear future; and then everyone started travelling, there were fights, we became extremely busy, bringing an end to our community. Which is O.K., I guess, but it’s a pity.

Anti-Diva series, 2008-2009

To what extent would you call this an intellectual cooperation?

Most of the time we admired the same artists. And, for example, all of us kept an eye on VVORK (vvork.com), asking each other whom and what they liked. We discussed art, criticized each other, too, but most of the time we acknowledged everything. We were into the same things, the same issues—the link between us was quite strong.

With whom have you created collective works so far?

Recently I had an exhibition with Katarina Šević, which included a publication as well. I worked with Tamás Kaszás and with István several times, in Bercsényi Gallery, to mention one, or in Trafó Gallery, in the exhibition Dear Painter. With István we displayed works together in Budapest Gallery as well. Way back, between 2000 and 2002, I ran the exhibition space Kirakat together with Anita Sárosi in Hattyú Street 10.

How significant do you consider Kirakat now, looking back?

It had two phases, actually. The first year was a series of one-month long exhibitions, mostly installation art. I used to be unable to see how this affected me; lately, however, I’m discovering more and more ties with my later works. The second year, we granted an exhibition space; anyone, mostly our classmates and friends, could apply with anything. We all needed to experience this freedom; I do consider it an important project.

Publicity, it seems, has been crucial to you, with the relation to public space always present in the background. This left several marks on your latest exhibition in Trapéz Gallery, as well as on earlier works, when statues were in the center of your attention. Your works are not monumental, yet they tend to be suitable for public spaces.

I’m glad to hear that; I often fear that my works might seem rigid to others. I want them to be open to conversation outside the art world. I’m not against extending my art to the public space, I have the ambition to reach out toward as many directions as possible. For example, I have always been fascinated by sculpture as well, although I never managed to acquire the art of it. Knowing all those techniques and the features of the materials would be great, but I’d move on anyway. I’d exploit its know-how, I’d accomplish one thing and another, before looking for something new; heterogeneity, mixing things is way too alluring.

Consultation with Malevich, 2008

Are there any works of yours that you consider to be sculptures?

I prefer to call them objects, due to my lack of technical competence, perhaps. They are so diverse, some are prepared objects; describing them with one label seemed to be the most beneficial. The term “object” can be applied to a wide range of things, unlike “sculpture,” which is classical, loaded. I enjoy the easiness of the word “object.”

The manipulation of everyday objects serves as a point of departure for your drawings, too, which remains to bear the possibility of monumentality.

True; as far as size is concerned, an object is much alike an everyday tool. I like ambiguity.

Referential object series, Watering pot, 2012

Aid device, 2013

Who is your ideal audience?

You have the professional crowd, which includes friends as well as colleagues, whose opinion is very relevant to me; and you have the other crowd, which is just as valuable. My father is a good example of the latter; as an architect he has the visual sensitivity and the curiosity toward art, you can tell when he appreciates—or disapproves—something. If something happens with him, he takes it in and processes it by himself. The ideal audience needs no directions as he/she can create his/her own narratives.

Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

I don’t usually enter such predictions, still, it would be a good thing, I guess, if I remained to be involved with art even 10 years from now. If my life was more stable, if people were interested in my art, if I had the opportunity to exhibit. Actually, I can’t even imagine it to be differently. I do ask myself from time to time, why is this good for me, with all its challenges? Maybe because of the charm the process of creating art means to me; when things become a whole and—hopefully—everything finds its place. It has its ups and downs, nevertheless, if the result satisfies me, then it’s O.K. I’d accept that 10 years from now as well.