A bourgeois from the Austro-Hungarian Empire for the culture

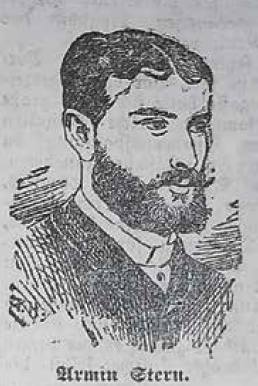

Armin Stern collector and composer

From now on if you walk along the Grand Boulevard of Budapest, you will know about the passions of some householders. How did the owner spend the rents of the apartments of 23 and 19 Teréz Boulevard?

At the turn of the 19-20 centuries in Budapest, the middle class played a very important role in aiding the national culture with their financial sources. One of their representatives was Dr. Armin Stern (1862 – 1922), who was well-known as a collector and a composer in the Hungarian capital. His collection was dominated by Netherlandisch masters and he donated some important paintings to The Old Masters’ Gallery of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest opened in 1906. Armin Stern’s interest toward the art of the ambitious bourgeoisie, the Netherlandisch paintings joined with his commitment to the bourgeois ideal.

The place and the significance of Armin Stern in the history of Hungarian private collections are summarized by Orsolya Radványi: “Althogh the paintings of Armin Stern weren’t sensational, but these were valuable additions of the Dutch collection. His donation could be appreciated as a gesture and this is the reason why his typical Budapest-bourgeois personality is memorable. His donations were followed by other representatives of the middle class.” Armin Stern, Frigyes Glück and Lukács Enyedi considered the importance of the wide publicity of art after famous collectors from the grande bourgeoisie class like Marcell Nemes, Ferenc Hatvany, Mór Lipót Herzog, Gusztáv Gerhardt and Adolf Pick. (1)

Armin Stern was a componist famous for one piece: his ballet entitled Zuleika was premiered in 1900 at the Hungarian State Opera House. His master was Anton Bruckner in Vienna and – according to the contemporary reviews – his ballet is under the influence of the French ballet, too. (2) As a typical bourgeois in the Austro-Hungarian Empire Armin Stern representatives a conservative taste, also as a specificity of his generation (his lifetime coincided with the existence of the Empire). This taste couldn’t appreciate the Secession and the Expressionism in the field of fine art and the twelve-tone technique (Second Viennese School) in the field of music…

Unknown Dutch painter, 1650s / Circle of Pieter de Hooch: Portrait of a Family – oil, canvas, 85,5 x 107,5 , Museum of Fine Arts Budapest (Inventory Number: 3928.) – Ⓒ Museum of Fine Arts Budapest - Hungarian National Gallery

A promising start

Dr. Armin Stern (he used his first name in its German version as Hermann (3) ) was born in Budapest on 2 March 1862 as a child of Friedrich and Fanny Stern. He studied at one of the most notable schools of Hungary, the Lutheran Secondary School. Then he studied law: he graduated at the Faculty of Law of the Budapest University of Science (now ELTE) in 1883. He worked at the royal country-court of Budapest’s District IV and he became an attorney. (4)

The turning point in his life was his marriage. When he was 25 years old – in spite of the opposition of his parents (5) – he got married to Cornelia Tafler (Budapest, 26 June 1866 – Budapest, 7 May 1937), daughter of the business magnate Koloman Tafler. Armin Stern’s brother Gyula Stern got married to Malvin Tafler, sister of Cornelia. His father-in-law, Koloman Tafler was one of the richest people of Budapest, when he began his political career. In the first two decades of 20th century as the greatest taxpayer of Budapest he became a virilist in the general assembly of Budapest. He was also a well-known owner of real property: he held and he ordered to build many palaces, mansions and apartment blocks not only in Budapest’s Grand Boulevard and its area, but in Vienna, too. (6)

Also Armin Stern measurably aided the build of the Hungarian capital: he was among the first persons who ordered to build mansions in the Grand Boulevard of Budapest, “although the construction was a very risky investment at that time”. (7) He ordered to build 23 Teréz Boulevard (1888-89, designed by Sándor and Gyula Wellisch), 41 Ferenc Boulevard (1892) and – with his father-in-law – 31/b József Boulevard (1893-95). (8) The Sterrn-Tafler couple held 75 mansions altogether in Budapest and in Vienna. (9) At the beginning of 1910s he lived in the representative palace of 19 Teréz Boulevard at Oktogon in Budapest (10) and 14 Hörlgasse at District 9 in Vienna. (11) His financial safety was ensured by his activity in various banks until his death. He participated in the establishment of the Hungarian General Confidential Bank, where he was a member of the Board of Directors, the same as at the Hungarian General Saving Bank. (12) Social sensitivity played an important part in his life: he led a lawyer’s office in 5 Akadémia Street (13) , where he solely dealt with family cases and protection of poor people… (14)

Armin Stern, the composer

Dr. Armin Stern had a keen interest in two fields of art: in music and – as a collector – in fine arts. He was an active and successful composer: his ballet entitled Zuleika was premiered on 18 April 1900 at the Hungarian Royal Opera House (now Hungarian State Opera House). His first master was the German composer Albert Dietrich, who was a member of the circle of Johannes Brahms. (15) Then he studied at the Vienna Conservatory as the pupil of the famous Austrian Romantic and Wagnerian composer, Anton Bruckner, who developed Richard Wagner’s musical style toward symphonic direction. At the beginning of his musical career, Armin Stern was known mainly for his piano pieces. (16) His artistic ambition was enthusiastically encouraged by his wife, who was the performer of his songs at that time…

Armin Stern collector and composer, donator of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest – Source: Politisches Volksblatt

A secondary and university schoolmate of Armin Stern, who used the pseudonym “Orior”, wrote a personal characterization in the newspaper Pesti Hírlap apropos of the premiere of Zuleika: „The composer is my dear old friend. We studied in the same secondary school and we graduated at the same Faculty of Law. He is elder but he finished his studies before me. I always liked him, who was the ideal of the diligence and the duty for me at all times. … We lived in the same house. Our windows opened into the court, we always were vis-à-vis. When I got into bed, the lamp was always switched, sometimes he read over the night. His passions were the learning and the music. He shared his time between the books and the piano. Later as lawyer he worked like other jobholders. Then he got married and he moved to Vienna for his wife’s sake. By this time he entirely committed himself to the music. His wife was his muse and his first critic. This cultured, nice lady is a singer, too. She was the first who performed her husband’s first songs in public. After minor works Armin Stern composed some more serious pieces: a sonata, a suite, even a string quartet, too. … The blond, phlegmatic Stern is a placid and a steady personality. He contemplates life with a certain philosophic serenity and he lives only for his family and the music.” (17)

The masterwork of Armin Stern is Zuleika, a ballet in three parts, which is laid in in the exotic Orient, in Istanbul. The story is written by the Austrian playwright and librettist, Eugen Brüll, who was the brother of the composer Ignaz Brüll (belonged to the Brahms circle) and a distant relative of Léda /Adél Diósy-Brüll/, lover of the famous Hungarian poet Endre Ady. (18)

Zuleika is sold into a pasha’s harem at a slave market. The Circassian Samil falls in love with Zuleika, but he doesn’t have enough money to liberate her. So he organizes the abduction from the harem, but the guards shoot him. After Samil’s death, Zuleika commits suicide with her lover’s knife. Finally, the couple find each other in the seventh heaven of Muhammad. The high level of the premiere was guaranteed by recognized artists led by the choreographer Cesare Smeraldi and the conductor Adolf Szikla, who was a composer, too. According to the reviews, it was a successful production. The first major composition of Armin Stern was criticized because of some minor faults, but on the whole, the composer was praised as a promising talent. (19)

Among the reviews, the most professional is written by a composer, who was also a music critic, Andor Merkler (1861 – 1920) in the newspaper Magyarország (Hungary) after the dress rehearsal, on the premiere’s day. Merkler composed numerous works for violin, piano, orchestra and a one-act comic opera entitled The lover of Fanchon, which was premiered in 1890 at the Hungarian State Opera House. He analysed both the faults and the values of Armin Stern’s ballet, emphasizing the influences of Léo Delibes (one of the most significant masters of the French Romantic ballet) and Anton Bruckner:

„The Zuleika’s music shows an unambiguous talent, such a talent, which could reach more significant results. It has such minor, formal faults, which precede the absolute artistic perfection in the most cases. On the other hand, the composer has a great sense of melody. His melodies are gracious, catchy and elegant, although sometimes inauthentic. Especially his dance music shows a very strong sense of rhythm beside its melodic character. It’s real, genuine ballet music. The waltzes are especially excellent. Zuleika’s Valse lento would have been honourable even for Léo Delibes. It’s so sweet and charming. The knowledge of Armin Stern isn’t ordinary. It shows the excellent school of Bruckner. So polyphonic elaboration, which manifests itself in some parts would be preceded by only profound, serious studies. He could acquire such preparedness which shows itself in the ornate harmonization and the correct forms of the modulations. In general, Zuleika shows a serious work which is unusual among the ballets. Especially it evidences mainly at the representation of feelings and characters. / … Zuleika has a lovely valse. It’s the Veil Dance... Armin Stern is proved a worthy follover of Delibes in this dance. … The final gallop is banal a bit, but very suitable for dancing.” (20)

The Zuleika was performed 17 times the Hungarian State Opera House between 18 April 1900 and 23 November 1901. (21) Thereafter Armin Stern’s ballet has been forgotten and the composer had never written any other work for the audience…

Armin Stern and the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest

Dr. Armin Stern could have a significant collection before the premiere of his ballet. Unfortunately, the birth of the collection couldn’t be reconstructed because of the incomplete documentation. There are only sparse documents.

Firstly the well-known collector of the Netherlandisch paintings introduced himself to the Hungarian publicity with a Hungarian painting. The opening of the Budapest Hall of Art (Kunsthalle) was one of the most important events of the Hungarian Millennium in 1896. The National Hungarian Fine Arts Society organized a representative exhibition, which demonstrated the Hungarian art in the spirit of contemporary academic style. Armin Stern lent Gusztáv Magyar Mannheimer’s painting entitled Pergola, Capri, which was presented at the exhibition with No. 816 in the catalog. (22) The connection of Dr. Armin Stern and the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest covers only three years, from 1910 to 1912. He donated nine Netherlandisch paintings for The Old Masters’ Gallery and two since then lost paintings for the Modern Gallery (now the Department of Art after 1800). He deposited five paintings at The Old Masters’ Gallery, too.

Dr. Armin Stern related to the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest by the director of the Old Masters’ Gallery, Dr. Gabriel von Térey, who was his close friend, too. (23) Térey, an internationally recognized art historian, who started his scientific career in Germany, considered the primary importance of the close friendship with the Maecenases from the grande bourgeoisie and the middle class. Marcell Nemes, Ferenc Hatvany, Mór Lipót Herzog, Gusztáv Gerhardt, Adolf Pick (among from the grande bourgeoisie), Armin Stern, Frigyes Glück and Lukács Enyedi (among from the middle class) altruistically donated paintings for the Old Masters’ Gallery in the spirit of that principle that the artworks – as public properties – must serve the common cultural development, not leaving them in the palaces of the propertied collectors. (24)

Armin Stern chose the paintings from his collection for the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest in common with Gabriel von Térey. He revealed his motivation of the donation in his letter to written to the director of the the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest, Dr. Ernst Kammerer on 12 April 1910. (25) His writing shows that he had a sincere idealism like his generation, which participated in the modernization of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Hungary: “I think I serve my deep sense of patriotic duty when I offer some paintings from my collection to the Museum of Fine Arts, an institute aiming to promote culture, even if I give only a few works. By this, I could contribute to the developement of our gallery and the public sense for the appreciation of fine arts.” Armin Stern has gained the title of court councilor by his donation. Ernst Kammerer acted on Stern’s behalf with a memorandum to Count János Zichy, the minister of religion and education, on 16 April 1910. The collector got the assignment two month later, on 12 June 1910 by the Emperor Franz Joseph I and the Hungarian Prime Minister Count Karl Khuen-Héderváry. (26)

Unknown Dutch painter, 1650s / Circle of Pieter de Hooch:

Portrait of a Family – oil, canvas, 85,5 x 107,5 (Inventory Number: 3928.)

The most valuable painting among the donations of Armin Stern is the Portrait of a Family, work of an unknown Dutch artist from the 1650s. The painter was probably was a member of the Delft School, possibly from the circle of Pieter de Hooch. The oil painting was donated as a work of Thomas de Keyser (c. 1596 – 1667), who was the most popular portrait painter in the Netherlands until the 1630s, when a decade younger Rembrandt (1606 – 1669) overshadowed him inspite of his artistic influence. The official valuation of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest defined the painting as a significant work of Keyser: “According to our valuation the worth of Thomas de Keyser’s work is 40.000 Krone, because it’s a very imposing painting of the excellent portrait painter of Amsterdam. In the painting there is a Dutch family of five members in a lit room.” (39)

Typical Flamish chandeliers in Emanuel de Witte's painting entitled Interior of the Oude Kerk (Old Church) in Amsterdam – Ⓒ Museum of Fine Arts Budapest - Hungarian National Gallery

A picture-in-picture. A painting representing a boy with an owl as a symbol of vanitatum vanitas in the Portrait of a Family – Ⓒ Museum of Fine Arts Budapest - Hungarian National Gallery

Although the painting was never defined as Keyser’s work in the international scientific literature, Gabriel von Térey queried his authorship just under a decade later, in 1924. From that time Keyser’s name was with a question mark in the inventory. In the publications, the work was marked as “Style of Thomas de Keyser”. (40) The leader of The Old Masters’ Gallery, then the general director of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest, Andor Pigler was the first who wrote the catalog of The Old Masters’ Gallery, in which the painting is signed as “In the style of Thomas de Keyser”. According to Pigler’s hypothesis its master could be the same as the painter of an unkown artist’s painting in the Bode Museum in Berlin (Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum at that time) with inventory number 750, which was destroyed under the World War II. (41)

In his study Notices sur quelques portraits néerlandais in the Bulletin du Musée Hongrois des Beaux-Arts Andor Pigler emphasizes that the painting in the style of Thomas de Keyser shows a practice of Renaissance and Baroque etiquette: in the common picture area the husband is heraldicly on the right and the wife is heraldicly on the left. (42) The painting represents the social situation of the genders and the generations in a Netherlandish bourgeoisie family. (The main figures are the married couple, an elder girl-child, a younger boy-child and a baby.) As the former director of the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie in Den Haag, Rudi Ekkart empasizes that the well-known book of the contemporary moralist literature, Jacob Cats’s book entitled Marriage /Houwelick/ (1625) is opened on the knee of the woman. In the background there is a painting (a picture-in-picture): a boy with an owl (43), in which the bird is a symbol of vanitatum vanitas. The sythetic catalog of The Old Masters’ Gallery published in 2000 defines the painting as a work of an unkown Dutch painter from the 1650s, without mentioning any school. (44)

The catalog of The Old Masters’ Gallery published in 2011, Rudi Ekkart’s Dutch and Flemish portraits 1600 – 1800 absolutely disapproves the Keyser’s style attribution and ascribes the painting to the Delft School of the third quarter of the 17 th century between 1655 and 1658, drawing the conclusion from the clothing styles. Rudi Ekkart discovered the influence of a prominent painter of the Delft School, a follower of Rembrandt, Pieter de Hooch (1629 – 1684) by the elaborations of the extremely slooping flagstone floor (the most eye-catching element of the painting), and the wife’s averted head. Ekkart emphasizes this theory is only a hypothesis… (45)

Emanuel de Witte: Interior of the Oude Kerk (Old Church) in Amsterdam

– oil, oak, 63,5 x 52 (Inventory Number: 3929.)

One of the popular subjects of the Netherlandisch painting is the church interiors drawn with architectural precision. One of the most significant masters of this style is the Duth painter Emanuel de Witte (1617–1692). After his studies in Delft he worked in Amsterdam. Beside the protestant churches he painted the Synagogue of Amsterdam, too. In his paintings he practiced the extreme contrast of the bright and dark lights and he realistically presented the church attendants (often with dogs). He often painted the eldest church of Amsterdam, the Oude Kerk (Old Church), which was consecrated in 1306 and became Calvinist in 1578. The pendants of the painting donated by Armin Stern are at the National Gallery in London, at the National Gallery of Art in Washington and at the Kramer Collection in Amsterdam. (46) In the catalogs of The Old Masters’ Gallery, Andor Pigler mentions the variations at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg, at the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister Kassel and at a prive collection in Enschede bought at D. A. Hoogendijk & Co. in Amsterdam in 1930. Armin Stern bought his Witte’s painting at Frederik Muller & Co. in Amsterdam, at the auction of the Viennese Ladislaus Bloch’s collection, including largely Netherlandisch paintings, on 14 November 1905. (47) The picture was listed with No. 77 in the catalog of the auction. (48) Armin Stern decided the eventual emplacement of Witte’s painting at the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest in conjunction with Gabriel von Térey. The official valuation of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest is the following: „We got an outstanding, church interior painting using warm colors of Emmanuel de Witte, who was missed from our gallery up to the present time. According to our valuation the painting’s worth is 20.000 Krone. In the newspaper Művészet (Art) Zoltán Takács described the work “as one of the best among church interiors of Emanuel de Witte. (50)

Emanuel de Witte: Interior of the Oude Kerk (Old Church) in Amsterdam – oil, oak, 63,5 x 52 , Museum of Fine Arts Budapest (Inventory Number: 3929.) – Ⓒ Museum of Fine Arts Budapest - Hungarian National Gallery

Unknown painter, South German School, end of 15th century: The Descent from the Cross

– oil, oak, 153,5 x167,5 (Inventory Number: 3930.)

This oil painting entitled The Descent from the Cross registered as a work of Hans Pleydenwurff (c. 1420 – 1472) in the collection of Armin Stern, who bougt it at the Kunsthandlung Friedrich Schwarz in Wien. (51) The authority of Pleydenwurff was neglected by Gabriel von Térey under the sight on the premise. Hans Pleydenwurff was the lead painter of Nuremberg. After leaving his city of birth, Bamberg he represented a naturalistic style by under Netherlandisch influence instead of his youthful Gothic style.

Unknown painter, South German School, end of 15th century: The Descent from the Cross – oil, oak, 153,5 x167,5 , Museum of Fine Arts Budapest (Inventory Number: 3930.) – Ⓒ Museum of Fine Arts Budapest - Hungarian National Gallery

The author was designated as unknown German painter in the valuation of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest: “Finally the The Descent from the Cross is a highly desired supplement of the gallery. The donator regarded the painting as a work of /Hans/ Pleydenwurff, but it was done by an excellent German painter around 1500. The eventful composition of the painting, the scene of the action is as worthy as the superb landscape. The worth of the painting is 15.000 Krone...” (52)

In the newspaper Művészet (Art) Zoltán Takács defined the work as “a painting from the beginning of 16th century” and empasized “principally the characteristics of the Swabian painting”. (53) According to Andor Pigler in the catalogs of The Old Masters’ Gallery the painting was done at the beginning of 16th century at the Lake Contance (Bodensee). (54) The most comprehensive anlysis of the painting is written by Hugo Kenczler in 1910 in the Archaelogiai Értesítő (Archaeological Bulletin). In his basic thesis, Kenczler queried the Netherlandisch art’s hegemonic influence to the German art and he localized the starting-place at the Lake Contance. His argument is the painting donated by Armin Stern: the art history “interpreted the development of the German painting as the result of the Netherlandisch influence. … It seems that the way of the development and the mode of the artistic expansion are connected with the trade between the cities. The development of the art went along with trade routes. The presumedly centre could be at the Lake Contance, in Reichenau, in Konstanz, in Basel, in this old trade and cultural centers… This painting is an interesting, beautiful and very late artwork of this school…”

Hugo Kenczler dated the work by the representation of the figures between 1475 and 1780, „when the individual representation of the psyche already has started, but hasn’t developed; when the representations of the body and the movements were very primitive.” He disagreed with the valuation of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest, which heightened both the figures and the background. Kenczler emphasized that the significance of the painting is in the elaboration of the background and the details. On the other hand he praised the enthralling colour harmony what he regarded as the proof of the attribution from the Lake Contance: in the background the nature and the town buildings “create a complexity. … Manifesting itself in these details, the involuntary pure perception of the aerial perspective’s nature is an artistic speciality of the Lake Contance region – drawing conclusions from the records – from the beginning of 15th century. In this period there weren’t such artistic tendencies in other regions of Germany. The other speciality of the painting is the purposively used unique colour harmony, which also a speciality of the Lake Contance region.” (55)

Gillis Mostaert: Scene in a Brothel

– oil, oak, 40 x 35,5 (Inventory Number: 4067.)

From Marten van Cleve’s The Holy Family to Gillis Mostaert’s Scene in a Brothel - this is the one of those few paintings, which title has been changed so much after numerous modifications that now it has a totally antithetical meaning.

A chicken and a cock in Gillis Mostaert's painting entitled Scene in a Brothel – Ⓒ Museum of Fine Arts Budapest - Hungarian National Gallery

Armin Stern could bought the painting at the Kunsthandlung Friedrich Schwarz in Wien, where it was for sale in 1900 as a work of Marten van Cleve (1527 – 1581), who painted peasant genre scenes and landscapes under the influence of Peter Bruegel the Elder and Hieronymus Bosch. (56) Stern donated the work to the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest as Cleve’s painting, too. In his letter to Gabriel von Térey written on 10 April 1911 he empasized the extraordinarily profane representation of the sacred subject (the sacrality of the painting was undisputed at the time): “I donate a painting of the Flamish Marten van Cleve representing The Holy Family in a profane conception to the Museum of Fine Arts... The offered work could represent the Flamish shcool of the 16th century beside the paintings of Pieter Aertsen and Joachim Beuckelaer...”

Gabriel von Térey didn’t query the authority of Cleve in his official valuation on 14 April 1911: “The donated painting is a very typical work of Cleve, a Flamish painter from the first half of the 16th century, who isn’t a well-known artist in Hungary. It fits very well into our Flamish department.” The value of the painting was 2000 Krone according to the valuation. (57) The Inventory Book of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest emphasizes the actualization and the contemporary setting of the subject: “The Holy Family. It’s represented in an interieur of a Dutch flat. … On the right, there is a woman, who is leaning on the door and talking with a craftsman, who stands oppositely her. In the background, a young boy carries bedclothes in a ladder to a young woman, who is waiting in a balcony and looking back...” The summary lists the animals (dog, cat, chicken and cock) in the painting, too. (58)

The authority of Cleve was queried for the first time by Sander Pierron in his book entitled Les Mostaert in 1912. He regarded the well-known Bosch-imitator, the Flamish genre amd landscape painter Gillis Mostaert (1528 – 1598) as the author and he entitled the work as The Holy Family at Peasants. (59) Mostaert was a close relationship with Clive: he painted figures in landscapes of other painters in Antwerp like Clive… The painting was lent to Utrecht in 1913 to the exhibition of the early Netherlandish painting and sculpture. The work was “attributed to Gillis Mostaert” with the note “perhaps from the circle of Marten van Cleve” in the catalog. The adequate of the subject was also queried for the first time: beside the title The Refugee Holy Family Resting (?) the name of Mary and the Christ Child were with question marks in the description of the catalog. (60)

Gillis Mostaert: Scene in a Brothel – oil, oak, 40 x 35,5 , Museum of Fine Arts Budapest (Inventory Number: 4067.) – Ⓒ Museum of Fine Arts Budapest - Hungarian National Gallery

After this exhibition the art history accepted the authorship of Gillis Mostaert, like in Paul Wescher’s writing in the Thieme-Becker Lexikon (Volume XXV.) in 1931. (61) Only Friedrich Winkler stated that the painting is much better than other works of Mostaert in his book entitled Die altniederlandische Malerei (1924). (62) In the catalogs of the The Old Masters’ Gallery Andor Pigler, unambiguously regarded Mostaert as author, gave the title Netherlandish household, but he suggested the possibility of another biblical subject with the title Paul and Silas at the Jailer’s Home, too. (63) The title of the painting is Flemish household in Orsolya Radványi’s book entitled Gabriel von Térey 1864-1927. A Conservative Reformer in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. (2006) (64)

The exhibition of the Manierist collection of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest entitled Sturz in die Welt. Die Kunst des Manierismus in Europa. at Bucerius Kunst Forum in Hamburg in 2008-2009 opened up the interpretive possibilities: the painting was exhibited with the title In a Brothel or The Flight into Egypt. (65) Now in the register of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest the work’s title is Scene in a Brothel. (66)

The interpretation of the painting has a very wide interval: the changes of the title signs the different conceptions. The title shows the changing of the moral sense in diverse historical periods, too. That is why there are totally different and contradictious interpretations in its own age, at the beginning of the 20th century and now. Beside the approach of the reception aesthetics, decisively determined by the public moralty, the recent scientific researches of the art history help us to reveal the circumstances of the creation and – it’s particularly prevalent in the case of the Netherlandish painting – the symbolics, which seems understandable nowadays. In this way, we can scientifically ascertain the authorial intentions. The recipients of the beginning of the 20th century saw “the Holy Family in a profane conception” (like Armin Stern wrote in his letter) in a Dutch milieu of bourgeoisie and craftsmen, emphasizing the contrast of the moral perfection of the Holy Family and the fallibility of human nature. The woman, the child and the elder, bearded man sitting further aren’t identifiable unambiguously as the Holy Family. The titles of Flemish household or Scene in a Brothel are more reasonable because of the setting. The latter title could be unambiguous because of the woman leaning on the door, her admirer (the craftsman), the woman in the balcony, her boyfriend carrying bedclothes and the animal symbolics of the painting. The correlation of the cat, the feminity, the fertility and the concupiscence is a widespread idea nowadays, too. According to the contemporary Netherlandish public opinion the dog was a symbol of the immorality and the obscenity. (67) The poultries were erotic symbols, too. (68) These symbols are integral parts of the Netherlandish iconography.

A broken life

The last decade of Dr. Armin Stern’s life was overshadowed by tragedies and crises both in his personal life and his career. His political career began in 1909 when he was elected as a representative of the District VI to the general assembly of Budapest. His official curriculum vitae, written at his assignment as court councillor, emphasizes that Armin Stern was a liberal democrat and “he participates with exemplary sedulity at the sessions of the general assembly”. His political ideas were very similar to the Vilmos Vázsonyi, but he thought that Vázsonyi’s significant liberal National Democratic Civil Party wasn’t efficient enough at country level. This could be the reason why Armin Stern joined in the National Party of Work established by Count István Tisza in February 1910. Stern was totally marginalized in the party from the very beginning. Stern was an applicant of District VI at the parliamentary elections. Tisza launched him against the popular and impressive Vázsonyi, who was finally elected by the citizans. Stern was well-known as composer and collector, but as a political novice – even if in a great party – he didn’t have confidence. (69) The scene of Stern’s political activity was reduced to the general assembly of Budapest, where he participated in the sessions to 6 December 1916. (70)

In the last decade of Armin Stern’s life, he lived through many personal tragedies. His only child, Rudolf had mental illness. Apropos of the inheritance process after his death the newspaper Pesti Napló wrote the followings about him: “This ill-fated young man … spent the greatest part of his life in psychiatries. As a youngster he was a deviant, uncommunicative and nervous person, but as a talent, he would have been successful. … Rudolf died in January 1930. In the last 14 years of his life he lived in the Schwarczer Sanatorium /in Budapest/. (71)

After a great marriage crisis Armin Stern divorced in 1916. Cornelia Tafler lived an aristocratic lifestyle and her second husband became the 17 years younger, well-known Austrian conductor, Rudolf Nilius (Bécs, 1883 – Bad Ischl, 1962). Before his death, Armin Stern also had a second marriage, but his wife remained incognito in the lamelight of publicity. As the final stage of his life, Armin Stern died at Christmas in 1922. His father-in-law, Koloman Tafler died few months later, in April 1923. After the death of his son Rudolf, there was a very long inheritance battle in the first part of 1930s between the two wives and the Gyula Stern – Malvin Tafler couple. His valuable collection has been dispersed. He handed down only his donations for the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest… (72)

The paintings are the following, with inventory numbers, the donation’s date and contemporary worth (in Austro-Hungarian krone):

I. Donations for The Old Masters’ Gallery:

1. Unknown Dutch painter, 1650s / Circle of Pieter de Hooch (donated as a painting of Thomas de Keyser): Portrait of a Family – oil, canvas, 85,5 x 107,5 – Inventory Number: 3928. – 12 April 1910 – 40.000 K

2. Emanuel de Witte: Interior of the Oude Kerk (Old Church) in Amsterdam – oil, oak, 63,5 x 52 – Inventory Number: 3929. – 12 April 1910 – 20.000 K

3. Unknown painter, South German School, end of 15th century (registered as a painting of Hans Pleydenwurff in Armin Stern’s collection; Gabriel von Térey established the unkown painter under the sight on the premise): The Descent from the Cross – oil, oak, 153,5 x167,5 – Inventory Number: 3930. – 12 April 1910 – 15.000 K

4. Ascribed to Jan Davidsz. de Heem: Still Life with Roemer, Silver Flagon, Bread and Oysters – oil, oak, 95,7 × 77,3 – Inventory Number: 3931. – 12 April 1910 – 10.000 K

5. Joos van Craesbeeck: Company Having a Chat – oil, oak, 72 x 50,5 – Inventory Number: 3932. – 12 April 1910 – 8000 K (27)

6. Jacob Gillig: Still Life of Fish by a River – oil, canvas, 67,5 x 88,5 – Inventory Number: 4066. – 31 January 1911 – 5000 K (28)

7. Gillis Mostaert: Scene in a Brothel (donated as Marten van Cleve’s The Holy Family) – oil, oak, 40 x 35,5 – Inventory Number: 4067. – 10 April 1911 – 2000 K (29)

8. Nicolas de Vree: Menagerie (donated with the title At the Zoo of Asterdam) – oil, oak, 28,5 x 36,7 – Inventory Number: 4372. – 25 May 1912 – 2000 K

9. Nicolas de Vree (donated as the painting of Abraham Storck, but it was inventorized as a work of Nicolas de Vree): Menagerie (donated with the title At the Zoo of Asterdam) – oil, oak, 29x37 – Inventory Number: 4373. – 25 May 1912 – 2000 K (30)

Among these donations for The Old Masters’ Gallery, the provenience of five paintings can be traced back further. Armin Stern bought the paintings of Joos van Craesbeeck (31) , Jacob Gillig (32) , Gillis Mostaert (33) and an unknown South German master (34) at the Kunsthandlung Friedrich Schwarz in Wien (I. Nibelungengasse 1.). The work of Emanuel de Witte was bought at the auction of Frederik Muller & Co. in Amsterdam (Doolenstraat 10). (35)

II. Deposited paintings for a short time at The Old Masters’ Gallery from 24 February 1912:

Carel Fabritius: Portrait of a Reading Man

Jan Pynas: The Preaching of St. John the Baptist

Gillis van Tilborch (Tilborgh): Company of Peasants in front of a Tavern

Willem de Poorter: Scene in the Temple of Diana

Pieter Lastman: Pastoral Idyll (36)

III. Lost donations for the Modern Gallery (now the Department of Art after 1800):

1. Otto Heinrich Engel: Girls of Friedland – oil, canvas, 62,4 x 83 – Inventory Number: 3952 – 15 September 1910 – 2000 K (later deposition in the Ministry of Religion and Education, where it was lost during the Revolution of 1956; it was listed among the missing paintings in the inventorial revision in 1957) (37)

2. Ary Scheffer: Maria with a Female Saint – oil, canvas, 73x59 – Inventory Number: 4070 – 29 April 1911 – 2500 K (during the Second World War it was destroyed as the deposit at the General Accounting Office) (38)

(1) Orsolya Radványi: Térey Gábor 1864-1927. Egy konzervatív újító a Szépművészeti Múzeumban. Budapest, 2006, Szépművészeti Múzeum. p. 87-88. (citation), 80. and 134.; Orsolya Radványi: Térey Gábor múzeumszervező és tudományos tevékenysége a Régi Képtár élén (1896 – 1926). Ph.D. Dissertation. Budapest, 2008, ELTE Művészettörténeti Intézet Doktori Iskola. p. 99-100. (citation), 87. and 145.

(2) The Opera House Commemorative Collection of the Hungarian State Opera- Review Collection

(3) Annamária Gosztola: A flamand barokk életképfestészet tematikai és interpretációs kérdéseinek összefüggései a holland realista festészet tükrében. – Ph.D. Dissertation. Budapest, 2007, ELTE Művészettörténeti Intézet Doktori Iskola. p. 129. The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 647/1910

(4) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 647/1910

(5) József Vajda – Mrs. Stern: A méltóságos muzsikus ügye – a másik oldalról. In: Pesti Napló, 3 July 1932, p. 36.

(6) Károly Vörös: Budapest legnagyobb adófizetői 1903—1917 In: Tanulmányok Budapest Múltjából, Volume 17., 1966. p. 145-196.

(7) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 647/1910

(8) http://budapest100.hu/ – Százéves házak Budapesten,; Károly Vörös: Budapest legnagyobb adófizetői 1903—1917 In: Tanulmányok Budapest Múltjából, Volume 17., 1966. p. 145-196.

(9) Békebeli milliomosok válása – halottgyalázási perrel súlyosbítva. In: Pesti Napló, 22 March 1932, p. 4.

(10) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 250/1911, 720/1911, 856/1911, 418/1912

(11) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 771/1910

(12) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 647/1910

(13) József Vajda – Mrs. Stern: A méltóságos muzsikus ügye – a másik oldalról. In: Pesti Napló, 3 July 1932, p. 36.

(14) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 647/1910

(15) Zuleika. In: Magyarország, 18 April 1900., p. 7-8.

(16) (k.i.): Zuleika. In: Pesti Napló, 19 April 1900, p. 3.; Operaszínház. In: Vasárnapi Újság. 22 April 1900, p. 255. – The Opera House Commemorative Collection of the Hungarian State Opera - Review Collection

(17) Orior: Zuleika – és szerzői. In: Pesti Hírlap, 19 April 1900, p. 6. – The Opera House Commemorative Collection of the Hungarian State Opera - Review Collection

(18) Ady Endre levelei (The Letters of Endre Ady). Edited by György Belia. Budapest, 1983, Szépirodalmi Könyvkiadó. p. 83. – 146. Ady Endre – Bíró Lajosnak. (Nizza, 10 October 1904.)

(19) The Opera House Commemorative Collection of the Hungarian State Opera - Review Collection

(20) Merkler Andor: A „Zuleika” zenéjéről. In: Magyarország, 19 April 1900, p. 8-9. – The Opera House Commemorative Collection of the Hungarian State Opera - Review Collection

(21) The Opera House Commemorative Collection of the Hungarian State Opera

(22) 1896. ezredéves országos kiállítás Budapesten. Az Országos Magyar Képzőművészeti Társulat által a városligeti új Műcsarnokban rendezett kiállítás ideiglenes tárgymutatója. Az új Műcsarnok alaprajzával. Budapest, 1896, Franklin Társulat Nyomdája, p. 48.; Ezredéves országos kiállítás 1896. A képzőművészeti csoport képes tárgymutatója. Az új Műcsarnok alaprajzával. Budapest, 1896, Országos Magyar Képzőművészeti Társulat, p. 103.

(23) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 771/1910, 250/1911, 720/1911, 856/1911

(24) Orsolya Radványi: Térey Gábor 1864-1927. Egy konzervatív újító a Szépművészeti Múzeumban. Budapest, 2006, Szépművészéti Múzeum p. 80. and 134..; Orsolya Radványi: Térey Gábor múzeumszervező és tudományos tevékenysége a Régi Képtár élén (1896 – 1926). Ph.D. Dissertation. Budapest, 2008, ELTE Művészettörténeti Intézet Doktori Iskola. p. 87. and 145.

(25) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 647/1910

(26) Hivatalos Közlöny 1910. No. 14., p. 209.: Személyi hírek / Címadományozások

(27) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 647/1910, 771/1910, 1110/1910; Annamária Gosztola: A flamand barokk életképfestészet tematikai és interpretációs kérdéseinek összefüggései a holland realista festészet tükrében. – Ph.D. Dissertation. Budapest, 2007, ELTE Művészettörténeti Intézet Doktori Iskola. p. 126-129.

(28) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 250/1911, 429/1911, 839/1911

(29) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 720/1911, 1547/1911

(30) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 1142/1912, 1547/1912

(31) Andor Pigler: Országos Szépművészeti Múzeum. A Régi Képtár katalógusa. Budapest, 1954, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 130.; Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister. Museum der Bildenden Künste Szépművészeti Múzeum Budapest. Bearbeitet von Andor Pigler. Budapest, 1967, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 161.

(32) Andor Pigler: Országos Szépművészeti Múzeum. A Régi Képtár katalógusa. Budapest, 1954, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 228.; Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister. Museum der Bildenden Künste Szépművészeti Múzeum Budapest. Bearbeitet von Andor Pigler. Budapest, 1967, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 262.

(33) Andor Pigler: Országos Szépművészeti Múzeum. A Régi Képtár katalógusa. Budapest, 1954, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 376. ; Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister. Museum der Bildenden Künste Szépművészeti Múzeum Budapest. Bearbeitet von Andor Pigler. Budapest, 1967, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 468.

(34) Andor Pigler: Országos Szépművészeti Múzeum. A Régi Képtár katalógusa. Budapest, 1954, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 148.; Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister. Museum der Bildenden Künste Szépművészeti Múzeum Budapest. Bearbeitet von Andor Pigler. Budapest, 1967, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 675.

(35) Andor Pigler: Országos Szépművészeti Múzeum. A Régi Képtár katalógusa. Budapest, 1954, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 633.; Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister. Museum der Bildenden Künste Szépművészeti Múzeum Budapest. Bearbeitet von Andor Pigler. Budapest, 1967, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 775-776.

(36) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 418/1912

(37) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 910/1910, 1822/1910, 863-05-1/1958

(38) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 856/1911, 1547/1911; Háborús műtárgyveszteségjegyzékek. I. füzet. Az Országos Szépművészeti Múzeum háborús veszteségeinek jegyzéke. Compiled by dr. Sándor Jeszenszky Sándor. (Manuscript) Bp., 1952, Múzeumok és Műemlékek Országos Központja. p. 63. (Item No. 563.)

(39) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 647/1910

(40) Rudi Ekkart: Old Masters Gallery Catalogs. Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest. Volume 1. Dutch and Flemish portraits 1600 – 1800. / A Régi Képtár katalógusai. Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest. 1 kötet. Holland és flamand 17 - 18. századi arcképek. Leiden, Primavera Press & Budapest, Szépművészeti Múzeum, 2011. p. 107-110.

(41) Andor Pigler: Országos Szépművészeti Múzeum. A Régi Képtár katalógusa. Budapest, 1954, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 297.; Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister. Museum der Bildenden Künste Szépművészeti Múzeum Budapest. Bearbeitet von Andor Pigler. Budapest, 1967, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 353.

(42) Pigler Andor: Notices sur quelques portraits néerlandais / Megjegyzések németalföldi képmásokhoz. In: Bulletin du Musée Hongrois des Beaux-Arts 21. 1962. p. 55-74., 132-140. /p. 135./

(43) Rudi Ekkart: Old Masters Gallery Catalogs. Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest. Volume 1. Dutch and Flemish portraits 1600 – 1800. / A Régi Képtár katalógusai. Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest. 1 kötet. Holland és flamand 17 - 18. századi arcképek. Leiden, Primavera Press & Budapest, Szépművészeti Múzeum, 2011. p. 107-110.

(44) Museum of Fine Arts Budapest. Old Masters’ Gallery. Summary catalog . Volume 2. Early Netherlandish, Dutch and Flemish Paintings. Edited by Ildikó Ember and Zsuzsa Urbach. Authors: Ildikó Ember, Annamária Gosztola, Zsuzsa Urbach. Budapest, 2000, Szépművészeti Múzeum. p. 49.

(45) Rudi Ekkart: Old Masters Gallery Catalogs. Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest. Volume 1. Dutch and Flemish portraits 1600 – 1800. / A Régi Képtár katalógusai. Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest. 1 kötet. Holland és flamand 17 - 18. századi arcképek. Leiden, Primavera Press & Budapest, Szépművészeti Múzeum, 2011. p. 107-110.

(46) https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/emanuel-de-witte-the-interior-of-the-oude-kerk-amsterdam – London, National Gallery – oil, canvas, 51,1 x 56,2 , Inventory Number: NG1053

(47) http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/Collection/art-object-page.130808.html – Washington, National Gallery of Art – oil, canvas, 80.5 x 100 cm, Inventory Number: 2004.127.1

(48) http://www.thekremercollection.com/emanuel-de-witte/ – Amszterdam, Kramer Collection – oil, canvas, 80.5 x 69.5 cm

(49) Andor Pigler: Országos Szépművészeti Múzeum. A Régi Képtár katalógusa. Budapest, 1954, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 633.; Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister. Museum der Bildenden Künste Szépművészeti Múzeum Budapest. Bearbeitet von Andor Pigler. Budapest, 1967, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 775-776.

(50) Collection Ladislaus Bloch de Vienne. Tableaux aciens. Vente le 14 Novembre 1905 chez Frederik Muller & Cie. /Catalog des tableaux anciens formant la collection de Monsieur L. Bloch à Vienne; la vente aura lieu à Amsterdam le 14 novembre 1905 ... sous la direction de M. M. Frederik Muller & Cie, Doolenstraat 10, Amsterdam./

(51) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 647/1910

(52) Hazai Krónika. Zoltán Takács:„AZ ORSZÁGOS MAGYAR SZÉPMŰVÉSZETI MÚZEUM…” In: Művészet. Edited by Károly Lyka. 1910. p. 268.

(53) Andor Pigler: Országos Szépművészeti Múzeum. A Régi Képtár katalógusa. Budapest, 1954, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 148.; Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister. Museum der Bildenden Künste Szépművészeti Múzeum Budapest. Bearbeitet von Andor Pigler. Budapest, 1967, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 675.

(54) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 647/1910

(55) Hazai Krónika. Zoltán Takács:„AZ ORSZÁGOS MAGYAR SZÉPMŰVÉSZETI MÚZEUM…” In: Művészet. Edited by Károly Lyka. 1910. p. 268.

(56) Andor Pigler: Országos Szépművészeti Múzeum. A Régi Képtár katalógusa. Budapest, 1954, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 148.; Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister. Museum der Bildenden Künste Szépművészeti Múzeum Budapest. Bearbeitet von Andor Pigler. Budapest, 1967, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 675.

(57) Hugó Kenczler: Emlékek és leletek. Krisztus levétele a keresztről. Festmény a Szépművészeti Múzeumban. In: Archaelogiai Értesítő. 1910. Volume XXX., p. 385-392.

(58) Andor Pigler: Országos Szépművészeti Múzeum. A Régi Képtár katalógusa. Budapest, 1954, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 376. ; Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister. Museum der Bildenden Künste Szépművészeti Múzeum Budapest. Bearbeitet von Andor Pigler. Budapest, 1967, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 468.

(59) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest 720/1911

(60) The Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest – Inventory Book - Inventory Number: 4067.

(61) Sander Pierron: Les Mostaert. Jean Mostaert die le Maitre d’Oultremont. Gilles et Francois Mostaert. Michel Mostaert, Brussels, 1912, G. van Oest. p. 116., 132., 152.

(62) Katalog. Ausstellung von Nordniederländischer Malerei und Plastik vor 1575. Utrecht, Gebouw voor Kunsten en Wetenschappen am Mariaplaats, 3 Sept. – 3 Oct. 1913. Utrecht, 1913, L.E. Bosch. p. 110-111. (105. tételszámmal); Andor Pigler: Országos Szépművészeti Múzeum. A Régi Képtár katalógusa. Budapest, 1954, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 376.; Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister. Museum der Bildenden Künste Szépművészeti Múzeum Budapest. Bearbeitet von Andor Pigler. Budapest, 1967, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 468.

(63) Ulrich Thieme – Felix Becker: Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart: unter Mitwirkung von 300 Fachgelehrten des In- und Auslandes. XXV. Leipzig, 1931, E. A. Seemann. p. 189.

(64) Friedrich Winkler: Die altniederlandische Malerei. Die Malerei in Belgien und Holland von 1400-1600. Berlin, 1924, Propyläen-Verlag. p. 386.

(65) Andor Pigler: Országos Szépművészeti Múzeum. A Régi Képtár katalógusa. Budapest, 1954, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 376.; Katalog der Galerie Alter Meister. Museum der Bildenden Künste Szépművészeti Múzeum Budapest. Bearbeitet von Andor Pigler. Budapest, 1967, Akadémiai Kiadó, p. 468.

(66) Orsolya Radványi: Térey Gábor 1864-1927. Egy konzervatív újító a Szépművészeti Múzeumban. Budapest, 2006, Szépművészéti Múzeum. p. 422.

(67) Annamária Gosztola: Gillis Mostaert: Im Bordell oder Ruhe auf der Flucht nach Ägypten. In: Sturz in die Welt. Die Kunst des Manierismus in Europa. Hamburg, Bucerius Kunst Forum. 15. November 2008 - 11. Januar 2009. München, 2008, Hirmer Verlag. 15.

(68) The Register of the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest

(69) Annamária Gosztola: A flamand barokk életképfestészet tematikai és interpretációs kérdéseinek összefüggései a holland realista festészet tükrében. – Ph.D. Dissertation. Budapest, 2007, ELTE Művészettörténeti Intézet Doktori Iskola. p. 72 and 127.

(70) Annamária Gosztola: A flamand barokk életképfestészet tematikai és interpretációs kérdéseinek összefüggései a holland realista festészet tükrében. – Ph.D. Dissertation. Budapest, 2007, ELTE Művészettörténeti Intézet Doktori Iskola. p. 108. and 143.

(71) Sturm-féle Országgyűlési Almanach 1910-1915. Edited by Ferenc Végváry and Ferenc Zimmer. Budapest, 1910, Pázmáneum Nyomda és Irodalmi Vállalat. p. 472.

(72) http://archivportal.arcanum.hu/szkj/opt/a100322.htm?v=pdf&a=start – Budapest Municipal Assembly 1873-1949 (Database)

(73) József Vajda: A „méltóságos” muzsikus, a „Zuleika” szerzőjének háromszoros hozománya. In: Pesti Napló, 26 June 1932, p. 11-12.

(74) Békebeli milliomosok válása – halottgyalázási perrel súlyosbítva. In: Pesti Napló, 22 March 1932, p. 4.; József Vajda: A „méltóságos” muzsikus, a „Zuleika” szerzőjének háromszoros hozománya. In: Pesti Napló, 26 June 1932, p. 11-12.; József Vajda – Mrs. Stern: A méltóságos muzsikus ügye – a másik oldalról. In: Pesti Napló, 3 July 1932, p. 36.