“I’ve always tried to think in terms of community, in terms of the whole of my profession”

A conversation with Imre Bak

The entire Artmagazin editorial board travelled to the city of Paks when its Gallery showcased a retrospective of Imre Bak’s works, curated by Dávid Fehér. The artist himself took us on a tour of the exhibition. This interview is an edited version of our conversation there, touching upon the topics of predecessors, experiences abroad, Béla Hamvas, the art of a lifetime, divisions between art historical eras, the illusion of space, and the relation of art and profession. (See the video version of the interview on Artmagazin Online!)

Imre Bak: My “oeuvre” now spans over 50 active years. I graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in ’63, and what I consider to be my art started to take shape in the mid-’60s. This was only a few years after the revolution of 1956 in Hungary. The art scenes of the neighbouring countries – Czechoslovakia, Poland, Yugoslavia (Slovenia, Serbia) were much more vibrant and energetic at the time, so, besides modern Hungarian art, they served as one of our main sources of inspiration. Thankfully, the masters of the European School (1) were still among us, and we had the chance to meet Dezső Korniss, Endre Bálint, Tihamér Gyarmathy, Tamás Lossonczy, and even Lajos Kassák. On the one hand, they told us the story of how Hungarian modern art emerged and evolved, on the other, they were in touch with artists abroad and could pass on information about 20th-century European art as well.

Artmagazin: Did you also meet them informally? Were you allowed to visit them at their homes? How did all this unfold?

They all lived under rather absurd conditions, confined to their tiny apartments, and were extremely cagey because of their precarious situation. But then they slowly realised that we are the new generation, and we intend to continue what they had started. Eventually, we became more than just colleagues, we were friends. My familiarity with Hungarian masters, combined with my travels in the Eastern Bloc, were my reference points when I first received a passport to Western Europe in ’64. Still, what I experienced there was a huge shock for me, because our Hungarian masters didn’t have much knowledge about the radical changes that took place in the international art world and in the on-going art historical processes. In ’64 in London, for example, I saw a very important exhibition (54-64 Painting & Sculpture of a Decade, Tate Gallery, London, 22 April–28 July 1964 – ed.) that showcased the art of the fifties and sixties; what the French call “Tachisme”, the Germans “Informel” and the Americans “Abstract Expressionism”. In other words, what started in the ’40s and ’50s, was to turn into the art of the ’60s, into pop art, minimal art and many other things. Seeing this exhibition made me understand this transition. This inspired the works I painted at the time.

Shape II, 1969, enamel on fibreboard, 117 x 240 cm | Gábor Kovács collection, Szekszárd

What else, apart from your travels to Western Europe, inspired you at the time?

It was in 1965 that I came into contact with a very progressive German gallery in Stuttgart that exhibited, alongside the German artists, artists such as Frank Stella, Morris Louis, Ellsworth Kelly, Kenneth Noland and others. My striped paintings that I painted afterwards show their influence. But if one’s seen a real Frank Stella, and then compares it to my painting, s/he can detect some very important differences – this was conscious on our part: we tried to follow international trends, but we didn’t want to simply copy the practices of others. We added personal and local factors, giving real meaning and stake to what we were doing.

What made you decide, in some cases, to use an unconventional canvas format?

In the 1960s, as we know, both international and Hungarian art history had already been through a lot. It became evident that the rectangle format of traditional painting is not necessarily a given. It was important for me to step out into space, in other words, to show that the image’s space can stretch beyond the frame, creating a closer relationship with the surroundings, and between the wall and the image. I had always wanted to create 3D painting. There was not much chance for this in Hungary, mostly due to the financial limitations, the bad condition of the studios, the issue of storage and other such difficulties, so I was content with creating illusions.

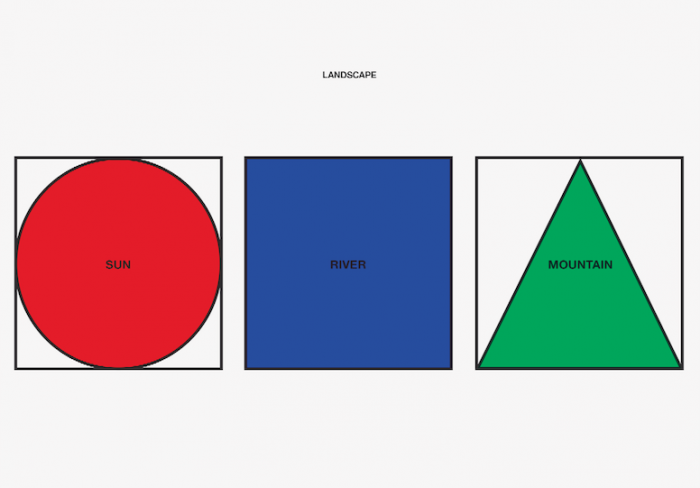

Landscape, 1972, tempera, letraset on paper, 510 × 690 mm | private collection, Budapest

Let us go back to influences and changes in style for a moment…

The next turning point was the series of IPARTERV exhibitions (2), about which we hear many legends, but not so much concrete information. Not so long ago, at Ludwig Museum’s pop art exhibition that showed mostly the art of the ’60s, about 70% of the IPARTERV works were on view. It was therefore possible to relive the atmosphere of the ’60s that was so open to international inspirations, experiences, and impressions, to see the artworks that such a milieu produced, and to view the way they were presented at the IPARTERV exhibitions of ’68 and ’69. 1968 is an important date also because the Documenta took place in Kassel that year, a Documenta that brought radical change to the artistic practices and the art world of the time. It was then that it became evident that American art has made a breakthrough in Europe. In other words, the long reign of Paris as the centre of the art world had come to an end, the new centre was New York, and this was obvious to anyone attending the Documenta of ’68. Figurative works, figurative versions of pop art, but also abstract, hard edge, colour-field… it was all there. The second IPARTERV exhibition also took place in ’68 in Budapest, showing figurative artists like Ludmil Siskov, György Jovánovics, Gyula Konkoly and László Lakner alongside abstract artists like Ilona Keserű, István Nádler and myself. I think the art historical significance of IPARTERV ’68 lies in the fact that when compared to Documenta ’68, it was evident that a whole generation of young artists had read the signs of the times. It was not only a single artist, like Csernus or Hantai in their time, but a whole group. This group had a circle of intellectuals around it, who then started rooting for us and supporting us. Of course all of this doesn’t make much sense without the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. The style, the hippies, the student revolution and all were integral parts of the milieu of the ’60s, it all formed a complex world view.

As the ’68 Documenta meant the end of an era internationally, the IPARTERV exhibitions also closed a period in the life of many Hungarian artists, myself included. In such cases, one always has the urge to move on. (At the age of 29, I experienced this feeling during the ’68 Documenta, where I saw the elaborateness of the works on display, and felt very much like a beginner in my profession.) This moving on, for the international art scene, happened the next year, in 1969, when the brilliant Harald Szeemann organised the exhibition When Attitudes Become Form in Bern, which then travelled on to the Stedelijk Museum and the Folkwang Museum in Essen. This again introduced some changes to the pop art-style of the 1960s.

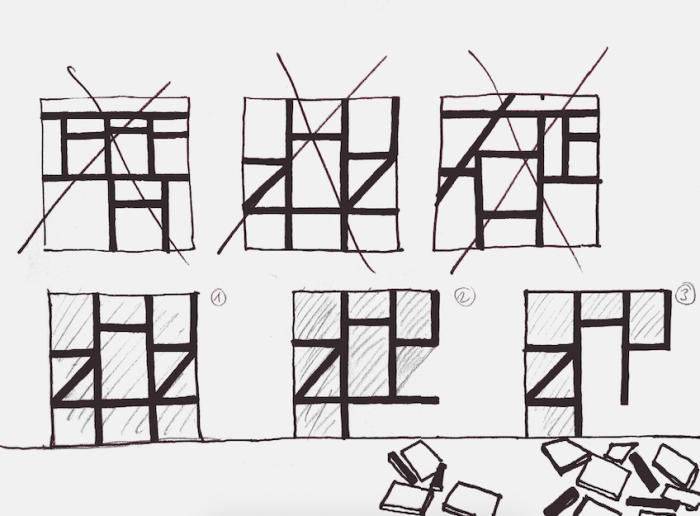

When, in 1971, my colleague Jovánovics and I had the chance to work in Essen’s Folkwang Museum, we were both intrigued by this turning point in art history. Having travelled under the pretext of tourism, we didn’t get an official permit to realise an exhibition, but we could utilise the museum’s workshop. It was the first time in my life that I had the chance to create objects, which would today be called “installations”. I found an interesting motif on a medieval, fachwerk-style house in Essen, which I then used in Fachwerk, one of the works I produced there. However, as it was an illegal exhibition, I couldn’t bring anything home, so the work unfortunately perished over the years. I was very interested in the relationship between the old and the new world during my travels in Germany, which is a country so modern and dynamic compared to Hungary, and where, with the exception of the bombed territories, the traditional old buildings had been very well preserved. The work I mentioned was very much missing from my ’70s oeuvre, so we decided to reconstruct it for the exhibition in Paks, with the same exact proportions, as I luckily still had the designs of the original.

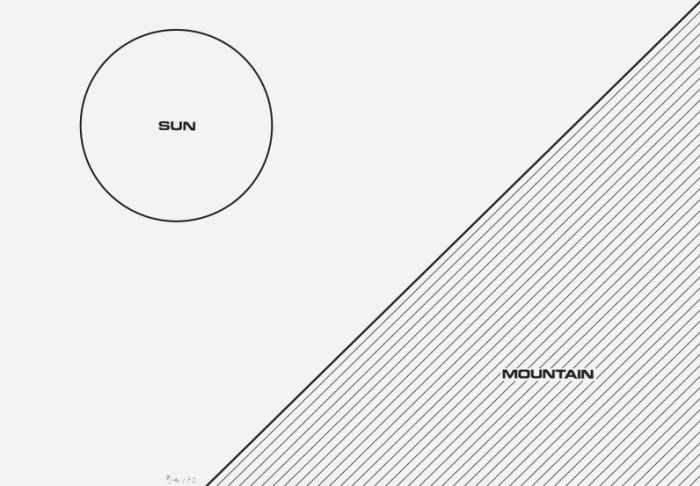

Sun-Mountain, 1972, ink, letraset on paper, 510 x 690 mm | private collection, Budapest

Did you bring the original designs home?

Yes, of course. The drawings and the sketchbooks as well. As the work is technically quite simple – a plastic foil fitted on plywood – I was able to recreate it myself, so it is an authentic reconstruction. But its most important feature is the one I’ve already mentioned: a new aspect of the image comes into play, and the customary rectangle form is left behind. To what extent is this still a conventional picture, to what extent is it still painting? These are the issues that the work deals with, but also the question of how the signs that evoke a bygone era work today, and how we read them in the present moment.

You also created some conceptual works in this era.

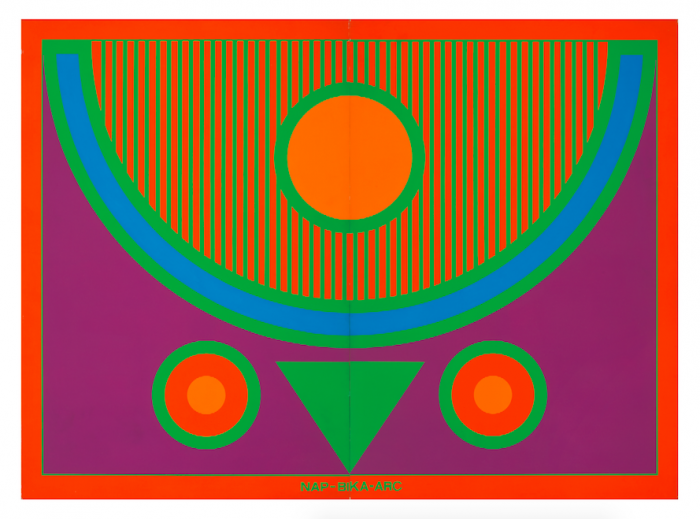

Yes, I made such works from ’71 until ’72, ’73 or maybe ’76. The aim was to reconsider what art is, what its function is, and how it makes me reflect on the big questions of life and the usage of signs. I was very interested in the combination of verbal and visual signs. A schematic landscape, a hillside, or a circle, which is a geometric form, but at the same time, it symbolically also stands for the sun, light, life, or man. At the time, I was fascinated by the complex working of signs. Let me allude here to Béla Hamvas, from whom, already during college years, I learnt a lot about how an artist constantly strives to explore the invisible layers of reality, existence, and even everyday life.

We usually chat too much about things – maybe this is what’s happening now as well (laughs). I was interested in the extent to which meanings could be condensed, the value they can be reduced to, but in a way that they’d still have a relation to their surroundings. What makes abstraction so difficult is precisely the fact that although we create something non-representational, there is still that umbilical cord, and you have to be able to link what is seen to some kind of reference point. This reductivity of the concept played a role in my later work as well. I also worked with photographs at the time, which again refers to the duality that I mentioned in the case of Fachwerk: the beautiful old manor houses and farmer’s houses in Germany are beginning to be surrounded by increasingly dense motorway structures. Are we destroying the past? Or is the modern world projected onto it? These are the issues I was interested in.

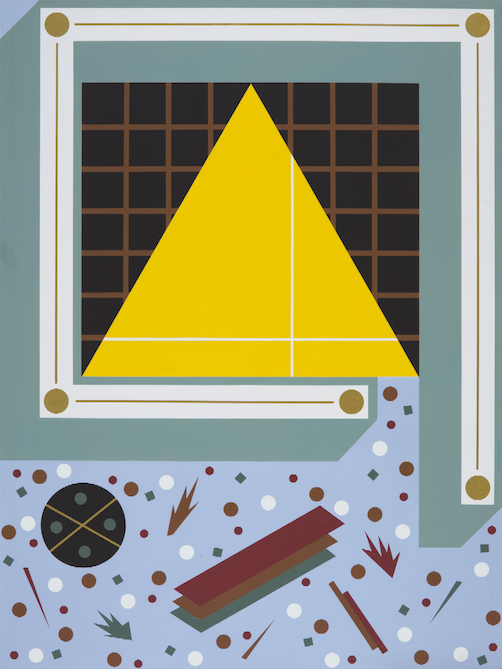

Bauhaus II, 1986, acrylic on canvas, 200 × 150 cm | property of the artist

How old were you at the time?

32, if I remember correctly.

Do these issues also include some personal dilemmas then? The questions of how one relates to the past and what one does in the present are very relevant at a certain age. So this must have been a pivotal period for you, and not only in terms of art.

Well, that is hard to say, but one thing is for sure: when we look for inspirations behind the works, we always have to look at the bigger picture of the situation in Hungary at the time. There was a huge difference between the rather desolate circumstances at home and the dynamically changing, Western European milieu. To what extent I was able to build up my own self-esteem is a question of personality. All my life – even today – I’ve been struggling with an inferiority complex; no matter what I’d achieved, I always made myself face more doubts, self-analysis, new tasks, and further work.

C. de Portzamparc, 1999, acrylic on canvas, 140 x 210 cm, | property of the artist

This is a rather unhealthy, self-reflexive state, isn’t it?

I think everyone should practise this. I have some colleagues and good friends whose temperament is rather enviable: they create a piece of work and it makes them extremely happy; they are very satisfied with themselves thinking a new masterpiece has been born. I’ve never been able to experience this. Not even in the case of Fachwerk, even though I quickly received some praise for it from some experts in the field in Germany. But this really is a matter of temperament.

Let’s focus a bit on the second half of the ’70s. Besides the Western European experiences, folk art was a local source of inspiration for you. How did this unfold in practice? Did you use some kind of a book, or did you spend a lot of time in an environment with such motifs, and then decided to transfer them to your studio?

At the end of the ’60s, this interest was rather instinctive, a matter of experimentation, and it became more concrete in the ’70s. As I mentioned before, I mixed in local characteristics with the Western European influences, and I found the embroidery patterns of Hungarian folk art instinctively – they provided me with a certain kind of geometry. This type of geometry was completely different from the one that characterised painterly practices in the neighbouring countries or England and America.

In 1974, being on the verge of starvation as it was impossible to make a living purely out of making art, I took a job at the Institute for People’s Education (Népművelési Intézet). That’s where I got the job of preparing various programs for the nationwide network of cultural centres, artists’ colonies and free schools, which were mostly frequented by art teachers. We thought of this whole project as if we were orchestrating training for art teachers. We managed to convince one of the cultural centres to paint a room white, and we needed good lighting as well to be able to put exhibitions on. There was a lovely atmosphere at the Institute between ’74 and ’79. This was the period of structuralism; some of the ethnographers were already moving on to cultural anthropology. They were publishing new analyses of folk art. We talked a lot about the example set by Bartók and Stravinsky, the way they used folk tradition to create contemporary music. In my own way, I was doing something similar at the time with art.

As for my works experimenting with reflections, they refer to Béla Hamvas in the sense that what is up there is the same as what is down here. This is an ancient fragment by Hermes Trismegistus, analysed by Béla Hamvas in a fascinating essay (Tabula Smaragdina – ed.) This book was my Bible for years.

Stories of Light V, 2014, acrylic on canvas, 210 x 600 cm | property of the artist

Who recommended Béla Hamvas to you?

It was during my studies that I met Sándor Molnár, who lived a few blocks away from Béla Hamvas on the Erzsébet királyné street. Sándor was the only one of us who had his own flat. There was a group of us at the time, from two different classes at the Academy, and we hung out a lot, went to workshops together and visited masters from the European School in their apartments; it was at such occasions that we had the chance to meet Béla Hamvas. His writings hadn’t been published yet, but Sándor asked for the manuscript, which we then copied and distributed among ourselves. Learning from Hamvas was a defining experience for me.

I have essays from this era that analyse the relationship between ancient Mexican stamp motifs and Siberian or Hungarian folk art motifs. It was an extremely inspiring atmosphere, we tried to analyse phenomena using techniques borrowed from structuralism or semiotics. A lot of work went into the pictures I created then: it took me a long time to figure out how to use the hard edge technique of the ’60s, while the agenda itself and the attitude were very far from what was relevant to me at the time. A more complicated world came into existence with the birth of concept art, a much more complicated structure of meanings, which I think was a precursor to the turn that took place in the ’80s, the one we call “postmodern”.

You explained the background to the Reflections series in terms of cultural history and visual culture. But let us look at them from another perspective: I remember seeing them for the first time, the way the halves met and formed a coherent whole: it was a similar feeling to finding the one you’d spend the rest of your life with. What was happening in your personal life parallel to the creation of these works?

In ’69, my son was born, and we had quite a few conflicts with my wife as she also had professional ambitions. Instead of being able to help, we were just waiting on each other to provide support. Obviously, tensions in my private life cannot simply be shunned when I’m painting, and this is also evident in my newest works. But it doesn’t appear too directly, and I’m trying to have a more esoteric stance on my life anyway. Let me refer to Béla Hamvas once again. When I was a student, I read one of his texts where he says you should build your life like a work of art. Now, when we, as young artists, dreamt of building our life’s work, our oeuvre, what we meant by that was creating this oeuvre out of series and fantastic pieces of art. And then there is Hamvas, who claims that it is your life itself that becomes the work. It took me a very long time to really understand what this sentence means, and to this day still, I try to live by it. For me, it means that one thinks of a picture as a mirror of self-development, an aspect of where one is at that given moment. It is extremely helpful to have a profession that always makes me realise where I’m at, and it also helps me keep steady in the flood of information that is life today. And there are so many exciting things happening in art. But in order not to get lost, one has to be able to relate everything to oneself. It is difficult to understand that I come first, and making art out of any given experience is only the second step. And also that the task is not simply to illustrate self-development. Millions of things have been done before me, and millions of things are being done simultaneously with my work. I have to acknowledge the art historical processes that I’m a part of. The important thing is to find myself at the points of intersection within this coordinate system. Where are my own, unique opportunities? To what extent does my mental state come into play; at which state of self-development am I at the moment? It is also important to understand the effect of everyday kerfuffle, difficulties, family relations, financial difficulties. I worked various jobs for 25 years in order to create the necessary conditions for my real work. I chose this over making a compromise. Art is a complex and difficult profession.

Sun-Bull-Face, 1976, acrylic on canvas, 120 × 150 cm | private collection, Budapest

You mentioned that during this period, in the intellectual atmosphere of the Institute for People’s Education and also your own praxis, the first signs of postmodern could already be detected. What direction did your work take in the eighties?

In ’79, I left the Institute for People’s Education. This wasn’t really my decision. I think the works I made at the time aren’t really related to modernism anymore; they show signs of something new. No one spoke about postmodern in Hungary back then. In Western literature, the concept of postmodernism probably already came up in the ’60s, in architecture, in the mid-’70s, and in fine art, it happened rather late, at the beginning of the ’80s, and I was in big trouble because of it. The artistic trends of the ’80s were partly figurative, partly expressive; this is the era of transavantgarde in Italy, Sandro Chia, Enzo Cucchi and the others, in Germany, Heftige Malerei, Neue Wilde (the postmodern version of early German expressionism), Fetting and many others… I felt that this wasn’t my cup of tea and I panicked. I was lucky because back at the Academy, I had a professor, Frigyes Pogány (the only master, apart from Barcsay, that I have fond memories of), who taught architectural history and who had such a big influence on me that I’m still interested in what is happening in architecture. Because the postmodern turn happened earlier in architecture, theoretical works like Charles Jenks’ classic book (The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, 1977 – ed.) were already available, and they helped me understand that postmodernism is a general cultural paradigm shift and not simply a matter of style. So it was architecture, architectural theory and design theory (the work of Memphis and Alchimia design groups and their theoretical discussions) that helped me understand the gist of postmodern thinking. What all this means in the Hungarian context has never really been thought through, especially not within fine art. In any case, as I mentioned before, it already became evident at the Institute for People’s Education that this layeredness and complexity of meaning, this new eclecticism, foreshadows a new paradigm.

Sign-materials of all kinds are mixed into my images from the eighties. In order to understand how this complexity can be handled, we have to once again investigate who I am, the figure behind the work. This vast art historical material, the result of analyses, can actually be treated like a ready-made. It’s not novelty and invention that take centre stage, but combinations, quotes, and references. When compared to earlier analytical works, this results in a densification of the layers of meaning.

Your works from this era (’80s and ’90s) are characterised by a colour scheme different from your earlier paintings: you started using pastel colours.

It is only natural that a period in an artist’s oeuvre is closely linked to every other artistic phenomena of the time. This changes maybe every five or ten years, I’m not sure. It is not easy to answer the question of how these changes express the zeitgeist. With geometry, people also have this misunderstanding that it’s some kind of a technical thing, you calculate everything ahead, add up the results and that’s it… but it actually involves a lot of emotion. A form has a certain size because that’s how it works well. It’s the same with colours, you have this feeling of “that’s how it’s meant to be”, and the standards of this are defined by the spirit of the age.

Pages from a sketchbook, 1971, fibre-tip pen on paper, 201 × 298 mm (per piece) | property of the artist

Who were your predecessors, what are the components of the sign-material that you worked with in the ’90s?

In the case of the painting Portzamparc 1999, for example I’d mention two components. French architect Christian de Portzamparc was one: he created a weird pink building in Paris, I think it was for the Opera house. The pink surface in the picture is an element borrowed from colour-field painting. It is painted with four layers. As the canvas soaks the paint in, I paint more and more layers, the first one almost disappears, but the surface retains its slightly flickering feel, which results in an illusion of three-dimensionality. In other words, I don’t seal the surface with this pink, it becomes penetrable, I’m able to walk into it. (This is not my own invention, but Mark Rothko’s and Barnett Newman’s from the ’60s.) On the bottom of the image, there are shapes laid over each other, much like in the works of Kassák, or in constructivism. I use two different techniques for creating the illusion of space: the Newmanian practice of colour-fields and the technique borrowed from constructivism. This is what postmodern thinking is like.

One might say that in the following years, the 2000s, the entire scale of your canvases changed. You mentioned before that at the sight of a 6-meter-long painting, the question might arise: “why does an almost 80-year-old artist need to work with such sizes?”

Naturally, as this is very tough physical work and on top of it all, I paint my pictures horizontally. To be bent double for 50 years… it does take its toll on one’s spine, so I should be more careful. But I’ve always been fascinated by size, which is related to the experience of first seeing a Pollock or Newman’s Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue. So what’s the point of that? It’s all about space. The bigger quantity you have of a certain colour, the more convincing its three-dimensionality, the stronger and fuller the illusion of space. It’s not some sort of obsession to paint large pictures; I simply want to make it possible for the viewer to step into the image space. You stand in front of it, and it surrounds you, like with Pollock’s paintings. This is a different experience, it’s not like the classics, where you look into another world through a “window”. You are surrounded by the space of the image.

Reflection I, 1976, acrylic on canvas, 220 x 180 cm | Nudelman collection, Budapest

What makes space and the illusion of space important?

Space is a very peculiar concept. I look up at the sky, it is concrete but abstract, because it is infinite. The strange thing about art is that I use very concrete materials: canvas, wood, paint, etc. Yet, in the meantime, during the whole process, I strive to dematerialise all this, to make it disappear by the time the work is finished. And so that elusive something comes to life, something that can only be created during the process of painting. This is why I stick to this medium, and not film, for example, because I can only create this kind of magic through painting, where the material slowly starts to disappear and another substance appears in its place. I think this is also a symbol of our own existence: there is this flesh and blood figure. who looks a certain way, yet I’d like to think that this isn’t my essence. But rather that elusive something on which one works throughout his/her whole life. So this is why space and the illusion of space are important for me. If such a huge picture manages to draw the viewer into its space, then maybe it’s easier to experience the simultaneity of tangible and intangible than it would be in the case of a small picture.

When you speak of Jovánovics, you say “my colleague”. I assume people think some professions (like that of a doctor, for example) are “real” professions, while art is more like a form of self-expression, and can only be interpreted in terms of individual oeuvres. By speaking of colleagues, you go against this widely accepted view of art.

I’m not sure if you’ve noticed, but I always speak of art as a profession. Maybe once I said “my art”, but I’m very ashamed of that. Because it’s not my job to judge whether one is good enough at what they do to deserve the label of “art”. Our profession is full of great craftsmen, whose work is very important. To be sure, there is a certain understanding of art as something very individualistic, narcissistic. But I’ve always tried to think in terms of community, in terms of the whole of my profession, and place my own praxis within that. I don’t think I would’ve been able to realise all these works had I not had friends and colleagues in Hungary and beyond.

The video interview has been edited by Emese Mucsi and Tünde Topor.

Thanks to our interns, Katarína Bódiová and Réka Dankó for transcribing the interview.

Translated by Júlia Laki

(1) A Hungarian artists’ group, founded in 1945, whose aim was to cultivate avant-garde art and artistic exchanges between Hungary and Central and Western Europe. – trans.

(2) IPARTERV, named after their two legendary exhibitions at the Institute of Industrial Planning (IPARTERV) in downtown Budapest, was an artists’ group who were the first to experiment with neo-avant-garde art in Hungary, defining the work of a whole generation. – trans.