'I’m a late developer'

Interview with Kamilla Szíj, fine and graphic artist

Interview with Kamilla Szíj, fine and graphic artist

Kriszta Dékei: You were born and went to school in Budapest, but took your degree at the University of Art and Design in Offenbach am Main. Why?

Kamilla Szíj: After leaving secondary school, I studied window dressing and worked as a window dresser for four years. Then in 1981/82 I applied to the Graphics Department at the Academy of Fine Arts. I wasn’t accepted and realised that many people applied year after year trying to get a place. This put me off, so I decided not to get involved with it. In 1983 I went to Germany intending to study. In those days this was defecting, but I was in an easy situation as I was granted German nationality because of my family.

What was studying there like?

Looking back, I’m really pleased I studied there and not in Hungary because the Hochschule für Gestaltung was a very free art school. There was no pressure to specialize and everyone had to try their hand at everything in the first two years. I made videos and photos, painted and learnt typography, which I wouldn’t have done otherwise. Having completed that, you were free to concentrate on the area you liked best.

And that’s how you came to graphics?

I worked in the graphics studio in the basement. That was the place that appealed to me most, the calmest place. It was so calm that the teacher didn’t speak to me for six months. Of course, that was because – although I’m usually very prompt – I was late for the first lesson. My teacher told me off, and I, out of spite, didn’t ask anything for half a year.

© Photo by Christina Hartl-Prager

Is that why you began experimenting?

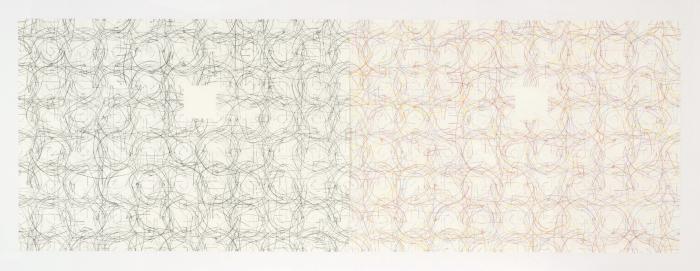

No. I didn’t like the point of reproductive graphics – that several copies are made of the same picture. There are so many images in the world, why make more of the same one? What excited me was how I could use drypoint technique yet make it different. At first I drew on the prints but I soon realised that this was a stupid way of doing it. Next I drew on four plates at the same time and created the drawing by turning the plates repeatedly and continuing the same lines. This had the effect of making the drawing denser. I made the images by printing different arrangements of the plates every time, thus I always produced a different image from the same cliché. I made many different variations, sixteen or so, and from these I compiled the final large picture. There are two things in this that are important to me.

Which are?

One is that the pressure to compose can be eliminated because the image composes itself. As I pick up the lines, continuing them on another sheet, a rhythmic structure is created. The other thing is that these are large images. The reason why the large size is important is not because it looks good or is exciting, but because this structure only becomes apparent when I put several variations side by side.

Even in your early works it is evident that you broke with the format imposed by the constraints of exhibiting in a confined space. These prints and drawings step out into space. You have displayed a double-sided work hanging away from the wall and you have also created a ten metre long cylinder that you lay on the ground, not to mention your corner pictures or your work that you presented slightly leaning. What is the reason behind this?

Maybe it was because at university I did a course called 3D Modelling, where we made installations. I really enjoyed the course and it went really well. It had a lasting effect on me in displaying large drawings and also in not framing them. Last year I had a solo exhibition, No More No Less, at the Óbudai Társaskör Gallery. There, for instance, because I deal with line and broken line, I drew a single line in space, nothing else, but in a way that its shadow was a broken line. I wanted to make an installation and a spatial drawing at the same time.

You once said that you were most interested in drawing.

I’ve always drawn in sketchbooks but I’ve never shown them to anyone because I think of them as my private business. There are drawings in these that I would never use in full or on a large scale but there are elements that I’ve been able to develop later. One such element is the hatching-like network of lines in the background which came increasingly into the foreground until it acquired its own life and became a component in my drawings on large surfaces.

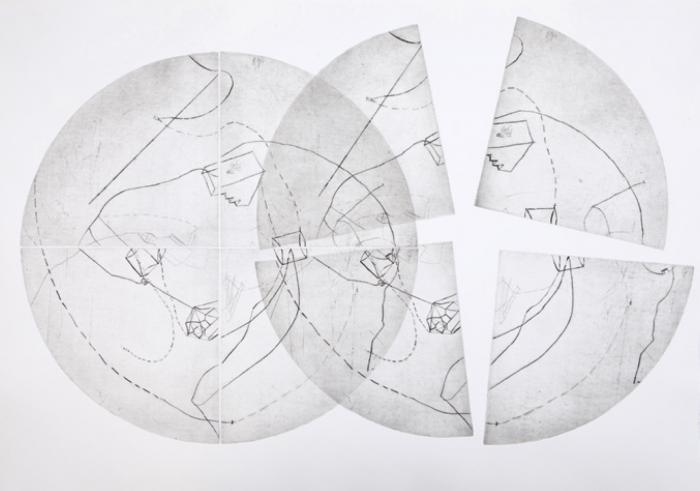

Untitled, 2011, drypoint, 70 × 100 cm

Why do you use such “simple” tools as pencil and paper?

When I started studying in Germany, computers and video were booming. Technical things were the rage. I, however, felt that it was not technology or current fashion that determined whether you make good things but the mindset, and new technical devices are not absolutely essential for this. My approach was to show to myself that I could express new thoughts using even the simplest, most conventional tools, pencil and paper. So I have retained paper and pencil or the print as minimal, reduced tools.

How do you avoid repeating yourself in such a confined area?

The title of my diploma piece in Germany was The Way Is the Goal. At the time this was not a conscious approach – it was just a kind of intuition – but it is true of my working method to the present day. I don’t jump this way and that but progress very, very slowly: development is all that matters. In this way I don’t repeat myself. I work around a problem and only move on when I feel I have resolved it. For me thinking “Wow! I’ve made something great – I’ll do three of four more like it” does not fit in with this. Of course, in today’s gallery-oriented world this may not be very practical but that’s how it is.

How do you make your large drawings?

For example, if I start work on a 1.5 by 3 metre sheet of paper, I only see half a metre of it at any one time as I work on a table. Naturally, I can more or less envision the entire work when I start but the details evolve as I go along.

No More No Less, installation, exhibition interior, Óbudai Társaskör Gallery, 2012

And how long does such a work take?

Months. It’s difficult to start, to pull myself together, because I know I’ll go headlong into it and all my free time will be taken up with it for a long time. The more I progress the more absorbed I become in it and I want to draw more and more frenetically. It’s an incredibly good feeling. It’s the making itself that is amazingly good in it.

It must be hard to make a living from this.

I had a nice professor who gave some advice to take with me when I graduated in 1989, saying, “You must know that only one per cent of artists can make a living out of their art anywhere in the world”. This reassured me as this also implies that being able to sell your work does not necessarily make you a good artist. At the same time, it relieved me of the burden of having to make my living from this alone.

After graduating, you returned to Hungary. Why?

I was awfully homesick. The university was great but I never felt at home in Germany. I was always looking to come back. After I returned in 1989, I lived through a year and a half when everyone believed that, in the knowledge of what was in the West and what was in the East, we would only adopt the good things from everywhere and leave the bad behind. This dream quickly vanished.

However good this period was, you were unknown in Hungary. How did you manage to break into the artistic circles here?

I had a few artist friends from the early 1980s but this wasn’t enough. An old friend of mine suggested that I should take and show my works to Gábor Andrási, the director of the Óbudai Társaskör Gallery. So that’s where my first exhibition was held. Later I learnt that this was the venue for many artists’ first exhibition. After that, I was invited to colonies for graphic artists in several places in the country (Makó, Szeged and Miskolc). These are luxuries in Hungary which no longer exist elsewhere. I hope they will keep going because they are very important. Most artists work alone but during two or three weeks you can discuss things far more intensely than sitting in a pub for a couple of hours.

LineaRES - von Punkt zu Punkt, exhibition interior, Heinersdorf, 2012

Since then you’ve also established relations with a couple of galleries.

What my old teacher said reassured me for years but I slowly began to realise that the art system now works differently. When Margit Valkó, who I also knew from the early 1980s, opened her gallery, she contacted me. I was very pleased though I had no idea what this involved as I was very green. It feels good to belong to a prestigious gallery but unfortunately it does not bring me as much as it does for the younger generation. I’m a late developer – I began my career with a delay of almost 10 years – perhaps that’s why my friends are ten years younger than me. Gallery owners, however, aim to have young artists or possibly older ones whose early works are sought at fairs. I can’t be taken to international shows like the young artists, because, no matter how different I feel, I belong to the middle generation. We fall between two stools, belonging neither here nor there. The most I can hope for is that my work will be more sought after when I’m seventy – although it could happen earlier…

It’s not common for someone who’s middle-aged to return to studying. Why have you done so?

Three years ago I went through a crisis in my private life. Everything that I believed was stable collapsed from one moment to the next. I had to rethink how to carry on. I applied to the doctoral school at the University of Fine Arts. I had three reasons. One was the grant – I have to live from something. The second was the company to break my loneliness. The last was that I am part of the older generation who did not think it was important to “explain” their art. Nowadays, however, artists are expected to talk intelligently about their works. It was very important to me to rethink for myself where I have come from and where I am going. I still can’t put everything into words fully but I believe I’m heading in the right direction.

But the explanation does not always directly equate with the quality of the artwork…

I agree with you. Some artists are able to talk about their concepts exceptionally well and I’m amazed how able they are to talk about their work. Today there are few exhibitions without some text or description on the wall next to the exhibited artworks. Once I just sat down in a museum and watched the people. I noticed that viewers looked at the descriptions first before turning their attention to the works. They didn’t approach the artworks with their own head and heart but guided by the viewpoint of what they were supposed to see. I don’t think this is right. If I explain my work, I deprive viewers of the opportunity of meeting it for themselves.

Is this why you don’t interpret your works, calling them all Untitled?

Exactly. Last year I had an exhibition in Paks and I explicitly asked that neither titles nor dates be displayed. I wanted to remove all information that may act as a point of reference to viewers so they may say “I see, I get it, that’s what it’s about”. People must be left to think what they think – to get into it if they can. If they can’t, that’s no big deal either. Nevertheless, the director of the art gallery in Paks asked me to write something. So I wrote something – not about making the works but why they did not have titles and dates.

Untitled, 2012, pencil on paper, 70 x 100 cm

Was there an artist in your family?

No. My mother was very interested in the arts. She really wanted to be an archaeologist but she had no chance to study. We went to museums a lot and we had good books at home. My uncle who lived in Germany was a jazz fan and he had an amazing collection. As a teenager I listened to the records he gave me. Apart from jazz and classical music, I really like minimal music, which I got to know through Group 180.

And your father?

My father, too, was very fond of music and learnt the violin when he was young. He was very keen for me to study music. I learnt to play the piano for seven years. In the first three years he had to force me to practise, not by beating with a cane but for an hour on Sunday afternoons when he was at home I had to play. I longed to go outside to play with the other children. I absolutely hated it until I reached a level where I could amuse myself with music. After that, I played for my own pleasure. It went really well and my piano teacher wanted me to study music. I saw how many untalented children there were and how much the teacher suffered with them, and I felt sure that I wouldn’t make a good pianist so I gave it up. But for a long time I wanted to start playing again and, when I sold a few works last year, I bought myself an electric piano. I got out my old scores and started practising again. I play at night using headphones so I don’t disturb the neighbours. It makes me very happy…

Apart from drawing and playing the piano, is there anything else that is important in your life?

The third thing is gardening. I have a garden with a vegetable patch and flowerbeds. A kind of peasant life, something inherited from my ancestors perhaps. All three things are equally important, but still drawing is my occupation, my work. The garden taught me to be systematic. Nature dictates. Certain things have to be done at the right time otherwise there will be no produce. You could interpret this as a must but it is an incredible feeling to be linked to something of a higher order. And it’s good to be involved in all three areas and all three have an actual result.

Untitled, 2000, drypoint printed on both sides, diameter 36 cm

Your works are very sensitive, even sensual. Have you ever been squeezed into the category of women’s art?

No, I haven’t, thank goodness. Once when we put our works on display in Offenbach, someone said that you couldn’t tell that a woman had made them. I liked that a lot.

So which category are you put in?

None. I don’t know if there is a pigeonhole at all that I could be put in. What I do does not really exist in Hungary so it is hard to classify. On the one hand, this is good because I don’t like hanging around in pigeonholes but, on the other, it makes life harder for me because I’m not invited to large thematic exhibitions. It doesn’t even enter into their minds, although sometimes my works would have a place there. I’ve only exhibited at one large group exhibition, What’s Up, in the Kunsthalle – I think I got in by accident. Solo exhibitions are important but for me it is more exciting to see my works in another context. It’s very interesting to see how they work next to artworks with an entirely different direction.

The original interview was published at Artmagazin, 2013/6, pp 24-30

Translated by Noémi Tréfás