I Perceived this Period as an Intermezzo

An interview with Endre Tót

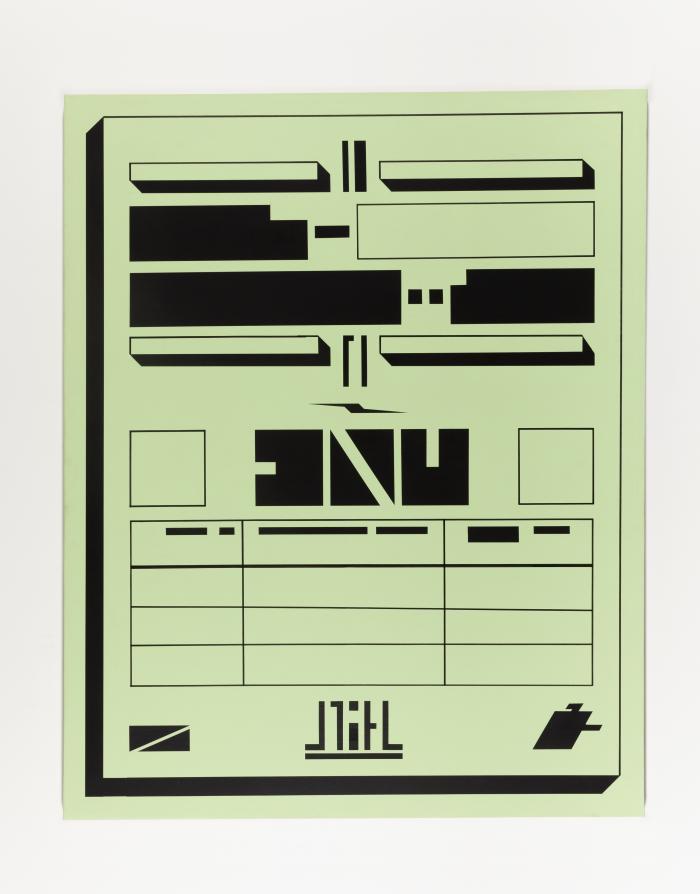

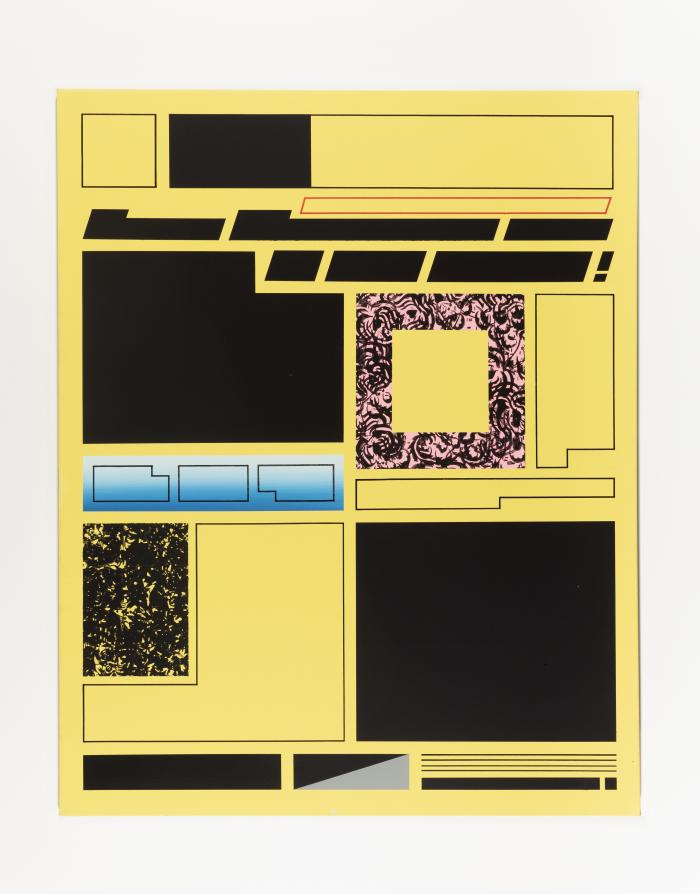

At its latest exhibition, acb Gallery presents paintings by Endre Tót, which waited in a storage for thirty years for someone to rediscover them. We talked to Endre Tót about these temporarily forgotten pieces of his colorful oeuvre, the influence of Informel painting, and the unexpected appearance of an artwork.

Róza Tekla Szilágyi: If I am not mistaken, the artworks on display at acb Gallery’s exhibition Layout Paintings 1988–1991 have emerged, after a long time, from a storage in Cologne. How did a segment of the oeuvre become, so to say, forgotten for such a long time?

Endre Tót: We have rediscovered these works after almost 30 years. What happened was, a year and a half ago the director of acb Gallery, Gábor Pados, visited me in Cologne. We went over to my studio, and he spotted some pieces from these, the Layout Paintings. To be clear, despite its considerable size, the studio was stuffed with pictures. The Layout Paintings were hardly visible. Pados indeed must have an eye for this; peaking into something partially concealed under a foil, and making out these works. I told him I have some fifty more of them, which I had taken to the coal cellar at home, so I could move around in the studio.

It was awfully difficult to rescue the large canvases from the back of the narrow, labyrinth-like cellar. The dust was so thick, the situation seemed absolutely hopeless. Fortunately, the wrapping around the paintings was excellent. In the end, a huge truck carried all the fifty pieces to Budapest.

What made you forget about these paintings?

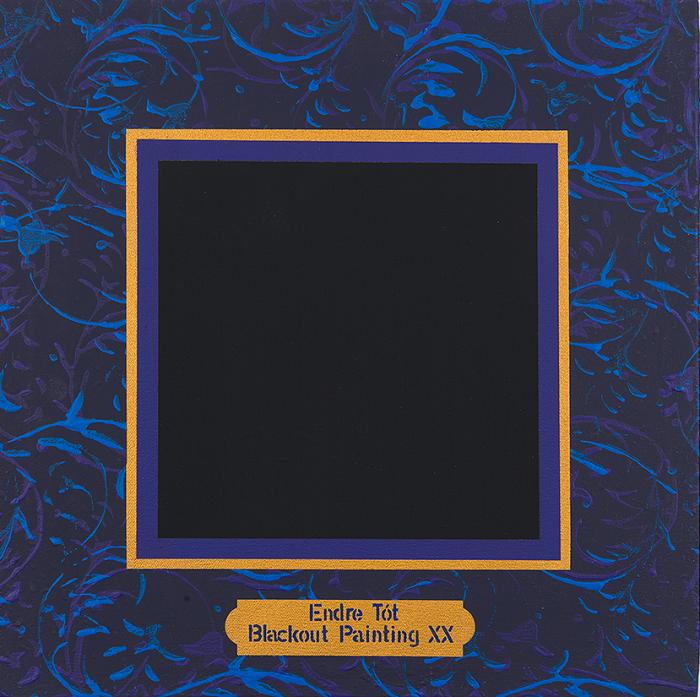

At the time, I perceived this period as an intermezzo, I was even somewhat afraid that these works would stand apart from my oeuvre. Prior to the Layout Paintings, I had already started working on the series Absent Paintings, which, if I may say so, made me quite successful in the West. In 1995, the Nothing Is Nothing exhibition at the Kunsthalle was drawing near, which, eventually, became revolved around the Absent Paintings; so I shifted my attention to the latter, instead of completing the Layout Paintings. In the end, I did not mind the Layout Paintings for thirty years.

Is “not minding” characteristic of your oeuvre?

To the extent that during the 1960s I used to be a painter par excellence. In Hungary, I was the first to discover Informel painting; around 1963–1964, I already made Informel works. I abandoned my painterly period, and traditional painting, too, almost in an instant; and, in the same breath, I forgot about most of the 1960s. When I emigrated from Hungary, I left behind my works from the 1960s, which amounted to 300–400 pieces. Although I didn’t care about their fate, they were safeguarded by my brother, who evacuated everything to his home, before the state took my apartment. When I move forward, I don’t care about things that happened earlier. That is what may have happened to the Layout series as well.

Can you recall how you encountered Art Informel for the first time?

A text inspired me to explore Informel. At the time, I was dating the daughter of Gyula Illyés, who spoke French because she had gone to secondary school in Paris. The Illyés family subscribed to the French magazine that was the first to seriously discuss Art Informel and its pioneer, Georges Mathieu. They published his manifesto, which, after Illyés’s daughter translated it for me, had a shocking effect on me. The content of Mathieu’s manifesto gave me tremendous confidence, and I said to myself, if painting like that really is an option, I’m saved.

Why did you abandon the Layout series?

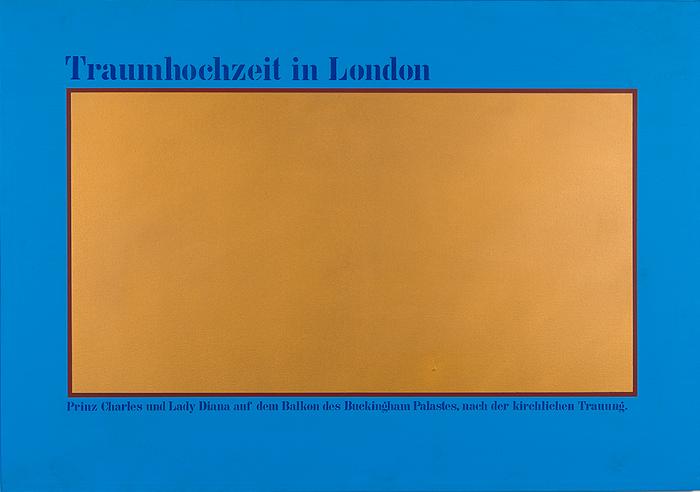

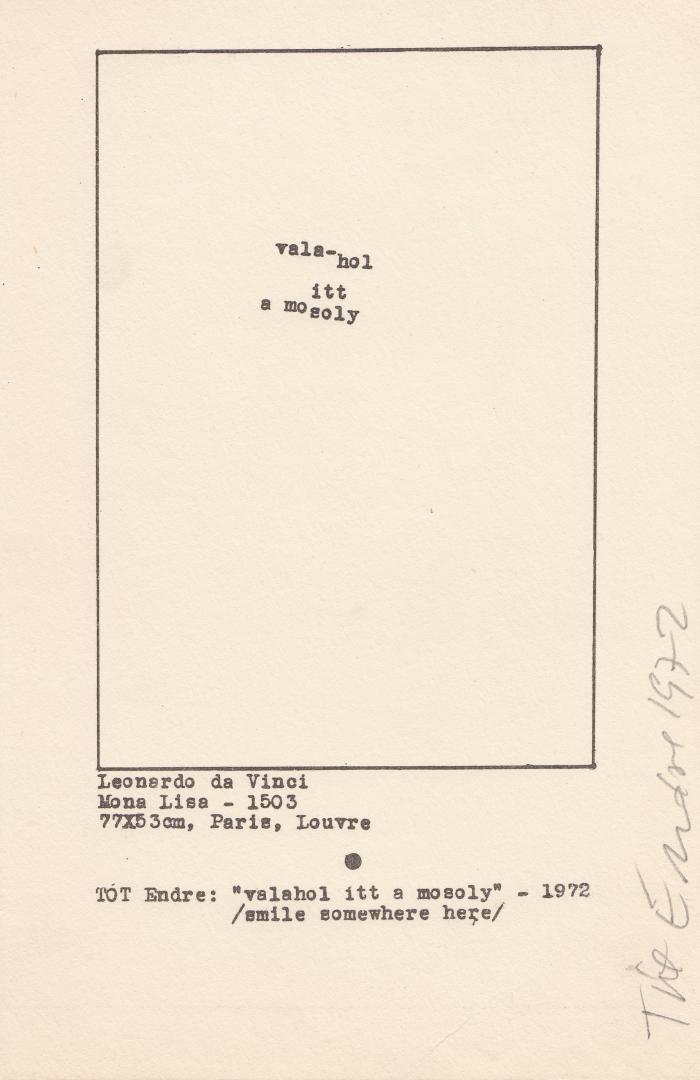

I stopped with the series because I felt that the paintings were too beautiful. And, as a matter of fact, I was working precisely against beauty. But to say something nice about them as well; they don’t fully stand apart from my oeuvre, I think, because they do refer, even if indirectly, to the Absent Paintings as well as the Blackout pieces, and also they have a marginal connection with an artist’s book I published in 1971, entitled My Unpainted Canvases, which had some symbolism in it, like my actual farewell to painting had. It was the aesthetics of emptiness and absence characteristic of these works, which resurfaced in the Layout series. In a highly ironic and critical way, of course, I addressed the tabloid press, which served as a point of departure for almost all compositions. I had an open page or the cover of a tabloid in front of me, which I transformed by emptying it.

The pictorial scale of the Layout Paintings resembles newspaper dimensions. Moreover, on several early pieces, you employed visual elements and arrangements recalling graphic design solutions. These may be among the factors that provide the series with a notion of freshness even today.

I think that it is the original painter who is behind these pictures. More than ten years ago, Géza Perneczky wrote that I was the most phenomenal painter among the artists living east of Amsterdam; and by that, he meant my works from the 1960s. Interestingly, I don’t think that it ever occured to Hungarians that my Informel works were done in an incredibly short time… In a period of two years, and not fifty, I made more than 100 pieces, and every one of them persisted. With my Informel period over, I regard the 1960s as a sort of a frenzy toward contemporaneity. The influence of Informel was followed by that of Pop-Art, and different remote objects appeared on my pictures, before I scribbled them over with my expressive brush.

How much time did you spend with one picture? Did you work on them separately, or did you paint several in parallel?

Only one at a time. What you’re asking is how fast was I working. My Informel pictures were done incredibly quickly, and no preparation had preceded them. Georges Mathieu, I must add, also stressed that there is no preparation in Informel. The sign precedes the meaning, he said, so he, too, titled his works only once done with them.

I dare to say that as far as Hungarian art is concerned, I was the quickest painter. Even large-scale or more complex compositions required fifty minutes at longest, but mostly I spent fifteen to twenty minutes on one picture. I was painting so fast, I often broke two or three brushes as I worked. The pace slowed, of course, when I turned to Minimalist pictures. Some required three to four days to finish, with six to seven hours of work a day. Those were time-consuming pieces.

A strange hastiness has always been characteristic of me, but with the Layout Paintings, surprising even myself, I took my time. I made exhaustive preparations, I even have four or five big, thick notebooks from the period, with preliminary sketches and drafts.

What is it like to see the Layout Paintings today? They look very fresh, despite being almost thirty years old.

They do seem fresh. If you allow me to celebrate myself, my works from the 1960s, I think, also have remained fresh. I should point out here that one or two pieces of the Layout Paintings were on display at a Cologne gallery at the time.

And what was the response?

I can’t recall much response. The current exhibition at acb Gallery is the true introduction of the series.

You tend to think in series, is there a motivation behind this?

I don’t have a precise explanation. What I may have is a very recent and fresh story about serials. On an earlier painting, I repeated the same motif five times, so that all the repetitions connected to each other. This was in 1970, and then in 1971, I took it to London in a large dossier full of similar compositions, hoping to find my luck with a gallery there.

Since my English used to be quite poor back then, I had help from local Hungarians who did not have such difficulties anymore. One accompanied me to Lisson Gallery, which already was one of the most progressive galleries of London and of Europe, too. As we entered, Sol LeWitt happened to be there; the gallerist was dealing with artists like him.

I showed the works I had in the dossier, and the gallerist’s reaction was very promising. Then, as he was aware where I was coming from, he asked me whether I intended to go back to Budapest. Yes, I replied without hesitation; that, however, prevented him from working with me, he declared, which was fair enough; coming from a Communist country, we hardly could travel, once every three years. So, our visit to the gallery was fruitless.

During the three weeks of this London trip, I stayed in the apartment of Michael Nyman, a world-famous composer today, known for the scores of Peter Greenaway’s films. I was invited to the UK to participate in a Fluxus exhibition, and these Fluxus people were friends with Nyman, but the two of us had not met before.

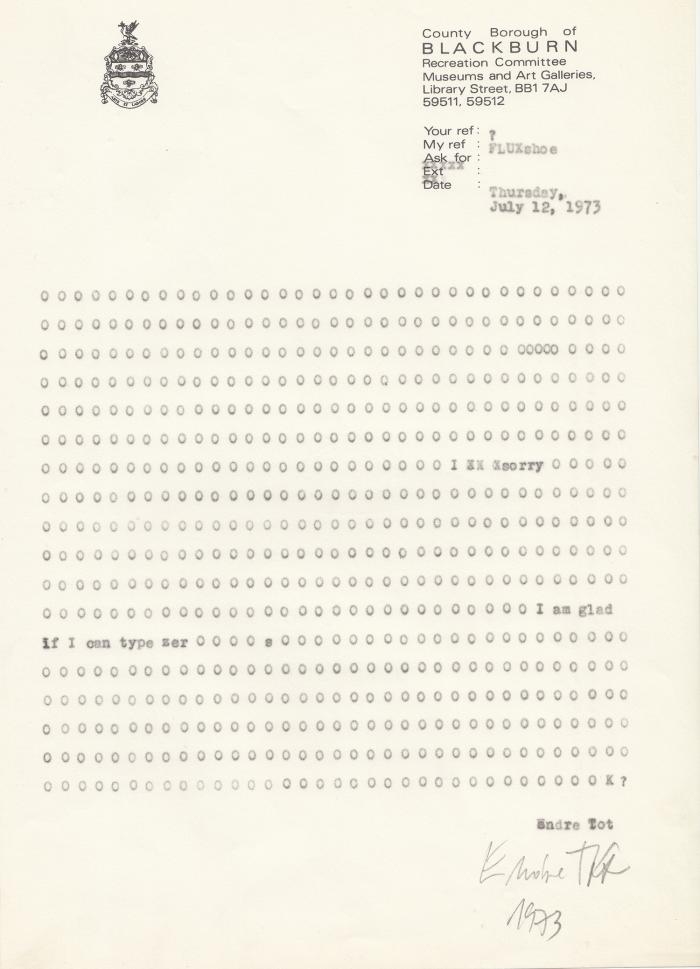

I kept on “zer0-typing” in London as well, filling hundreds of sheets with zeros. Occasionally, the sentence “I am glad if I can type zeros” appeared among the zeros. With the help of a local museum, we mailed some of them, so the act turned into mail art. We sent a couple to Nyman, too. Once, on my way back to the flat, I passed a cricket field, and had a hard time comprehending how that game could be enjoyed, which I later shared with Nyman. He replied, “sure, cricket is boring like Mondrian and your zeros.”

Fast-forwarding fifty years, Nyman moved to Italy, and recently came across me at the Milan Fair, at the acb Gallery stand. In 1971, I left the dossier with him, containing the serial works I had taken to London, and he kept them for fifty years. In Milan, he offered to give them back, and the works indeed have arrived since then.

Regarding the Layout Paintings, you said they had been “forgotten,” so to say, and you chose not to go back to the series later either. Still, can you perhaps identify elements that did turn up on later works after all?

Whether I could profit from the Layout series later? I don’t think so. It is characteristic of my oeuvre that once I was done with something, I never got back to it. I had a strange period during the early 1980s, when painting regained its popularity first in Italy with Ernesto Tatafiore and others, to which the Germans responded very quickly, owing, actually, to the Cologne school. And that painting really was passionate, which pushed me into a major crisis, because my impression was that I could paint like that, too. Yet, I also felt that painting like that was not allowed to me, because what I had achieved by then, by 1982–83, seemed quite clear-cut; I had been involved with Concept Art for fifteen years or so.

Then the Neo-Geometric Conceptualism of the mid-1980s, or Neo-Geo, was too confusing again. However, John Armleder, the most prominent figure of Neo-Geo, who had become the biggest celebrity during the late 1980s in a flash, was a close friend.

When did you return to work after the crisis?

In 1987, following an international Fluxus exhibition, I found a studio opportunity that I immediately seized. Up until that point, I had no studio space; it surely wasn’t necessary during the crisis, and before that I had been involved with mail art and public art mostly. Then, in 1989, a minor miracle happened. As all of a sudden I became impatient to show what I had achieved in that short time, I assessed the scene; as far as galleries were concerned, Cologne at the time maybe even outweighed London or Paris. I found this intriguing, quite well-known gallery, which Alfred Kren ran since he had given up his gallery in New York. I simply walked in, just like that, which seems pretty impossible today. And he visited me, saw my stuff, became enthusiastic, and wanted to take two large canvases straight to the gallery. At around midnight, that very evening, we carried the paintings there.

What were those pictures like?

They were the anteroom to the Layout Paintings. This was the first occasion that a gallerist really took me under his wing. A couple of months later, when he visited me again, he placed 5,000 Marks on my desk, wanting to do my first solo show, which he then did indeed. That solo show already included the Layout Paintings.

Looking back today, what significance do you attribute to the Layout Paintings?

That is an interesting and pressing question. What I can say is that the story of these paintings, I think, is not over yet. I’m really looking forward to seeing these works kick off in Torino, at the Artissima fair. Maybe after that I will have a more accurate answer.

Translation: Miklós Zsámboki

The translation of this article was created with the support of Summa Artium.