We Painted Winterscapes in the Summer Garden

A conversation with Orsolya Drozdik (part I)

It was thanks to her that the female point of view became part of contemporary Hungarian art discourse in the mid-1970s, and she has continued to push this ever since, even incorporating it into her curriculum as an instructor at the University of Fine Arts for many years. This interview, which focuses on the course of her life, maps the antecedents of all this, as well as the environment in which it emerged and the impacts and influences on her.

Tünde Topor: What kind of family did you grow up in? Was there an interest in art?

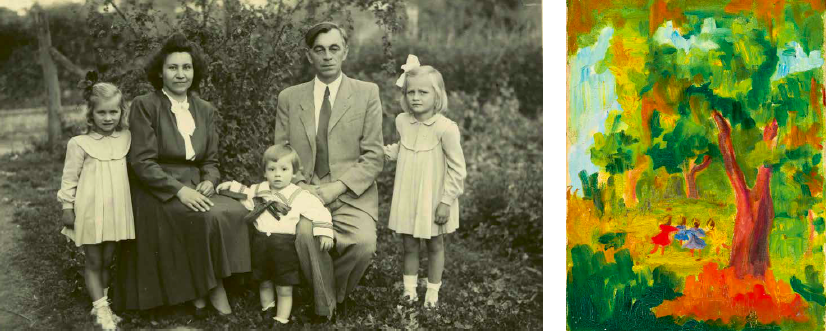

Orsolya Drozdik: I had a beautiful and a very difficult childhood. Between the ages of six and ten, I helped my mother, Erzsébet Kockás, care for my father, Béla Drozdik, who was operated on by Dr. Pirot for a brain tumor and who was brought home from the hospital in a half-dead state after the operation. We cared for him for four years in the belief that not only were we keeping him alive, but that one day he would recover from his illness. This can be extremely strenuous for an adult, but it is even more so for a child. So, I grew up fast and developed a strong sense of responsibility, which has remained part of me throughout my life.

Both my parents were educated people who were very fond of the periodical Nyugat (West). My father was born in 1902, for him, Nyugat captured the Zeitgeist, and he knew the literature of the circle of Nyugat very well. My mother was from Bratislava, more specifically she had been a deportee in accordance with the Benes Decree,[1] from Bratislava. She was born in 1920, and for her, social issues and reform ideas were important, such as how to build houses for the poor, how one can feel free within the given circumstances, and the counter-movements of modernism, including the ideas of Rudolf Steiner.

Later, as they belonged to the educated middle class, their property, as the property of a class enemy, was confiscated, and I grew up in an unfinished weekend house. They were both teachers, and as employees of the state, they were placed where there was a new job vacancy or simply a need. This is how my mother ended up in Abda, where my father started building the weekend house, and it was here that I was born, right after World War II.

We had a large bookcase and lots of books, but only a few of the books were in the room, the rest we kept in boxes in the attic because many of them were indexed as banned at the time. Many of our books (in particular the Révai encyclopaedias) had slash marks on them because when the Russian soldiers had come looking for watches, the “bourgeois” books had been slashed up with a knife. For a child, the sight of the slashes on the backs of all the books was shocking. This left a deep imprint on me.

This was the environment in which I grew up: in a small village, living next to the train station. The railroad tracks ran along the edge of our orchard, and the two-story building of the station looked magical. Most of our games were tied to this building. When we played, we pretended to be American Indians. We would press our ears to the tracks to try to hear if the approaching train was near. We got in a lot of trouble because of that, and the station master grabbed us by the ear. We children were alone a lot of the time.

When did you move away from Abda? As a secondary school student?

I had already attended a school in Győr for the second half of my elementary school years, and then I went to Péterffy, a non-coeducational girls’ secondary school. The building of the primary school was on the bank of the Rába River, the place where the so-called gentlemen's kiosk had been – it was here that even my father had come before the war to talk about literature and politics and to smoke his daily half-cigarette. The dinner guests who came to my parents’ house were very erudite, they were Nyugat and Ady fans - then after the war some of them worked as night watchmen. They were not artists, just sophisticated consumers of culture for whom progressive ideas and the progressive mentality, which included feminism on my mother’s part, was important.

Were you drawing at the time?

I started drawing when my father died. My mother had figured this out very well, she was a very smart woman. There was not much talk about therapy at the time, but she knew about psychotherapy.

I first wanted to be an actress, so they sent me to a dance school where I refused to learn the compulsory dances, I only knew my own dance, and so they said it would be a waste of time to try to teach such a child. I was also discouraged from learning to play the violin for exactly the same reasons, because I only played what I wanted to and I couldn’t learn what they put in front of to me. They also said I didn’t have a good ear, so I was also relieved because of that, but we both forced an artistic career.

When my father died, my mother put a bouquet of flowers in front of me. She placed it between two lilac bushes, on the table where we had lunch on Sundays. We had a very beautiful, well-kept garden (my mother worked in it, today it would be labelled organic gardening). She said that if I wanted to be an artist, I should paint this bouquet, and she brought me oil paints. Later that same summer, in 1956, she brought a winter landscape. We had paintings in the house, among my father’s friends there had been amateur painters, and my father had also painted, using watercolours. My mother had a beautiful drawing instruction album which she herself had compiled. As for where this winter landscape came from in the middle of summer, I don’t know, but I had to copy it. She and I were painting the winter landscape together in the summer garden and suddenly she said, “child, I’m not as good at this as you are, do it alone!” Though I loved painting with her and she was every bit as deft as I, but she gave me an enormous amount of self-confidence with that one statement.

In Győr, László Alekszovics had a drawing class in Baross Street, and I was about twelve years old when I started attending it after school. I received a lot of praise, but they didn’t give special attention to me separately, I stood on my little stool and drew. At home too I stood on my stool when I cooked – here too it was the same: a small child was given an adult job. Incidentally, this little stool was around for a long time; when my mother died in 1996, many such things re-emerged. There were a lot of things I didn’t throw out because of the emotional attachment to her, I consider all of her objects as a bit part of my art, and her too.

When my helpless father was dying on the foldout recliner, there was a long table next to him in the room which could accommodate fifteen people. My mother held dinners on a regular basis, there was always company in the house – even though poverty was dire and there was little of anything at home. My mother learned to cook from her aunt, grandma Pálffy, who was a well-educated and erudite woman with good taste and who knew everything there was to know about running a good household. And I too learned these same things from her. For example, when I was around 10 or 11 years old, I learned how to stretch and tug the strudel dough on that big table. I associate this memory with the death of my father. My father died on July 2, 1956, yet I remembered a kind of autumn, September mood. Later, when I left Hungary, I cut these ties of memory.

What was your relationship with your grandparents like? You mentioned that your mother had been displaced from Bratislava.

The Pálffy family lived in Dunaszerdahely (Dunajská Streda, Slovakia), and we regularly visited Czechoslovakia, going through Komárom. My grandmother’s sister, grandma Pálffy, kept the family together in the mansion, and she took great care that everyone speak Hungarian fluently and know Hungarian literature and history. The three of us children took Hungarian books across the Komárom footbridge. They were in very heavy packages, I remember how they pulled on my arms on both sides, but it was even harder for my little brother, who was five years younger than me. Grandma Pálffy set up school for family members in one of her rooms, and we would get a smack on our nails if we didn’t know a given Hungarian poem. My mother knew hundreds of poems by heart, and she would recite Ady while doing the laundry. I too would remember them for a long time, and writing has always been an important part of my art. But we also got Batya shoes over there, which were much better and more comfortable than what was available in Hungary.

My father was a dandy before his illness. Even in our small apartment, we had at least three hundred shirts and twenty coats, beautiful garments, while the world around us seemed tiringly bleak and shabby. This wardrobe was an escape for me. When I was young, it frustrated me so much that I couldn’t have a wardrobe like that, well now I do, I have made up for it. In Abda, a seamstress worked in the station building, and my mother ordered things from her, we did not wear the garb from the May 1 Clothing Factory.

So, we crossed over to Dunaszerdahely, but we never talked about it, or about what was said there. Even as a child, I knew that we shouldn’t talk about what we heard at home because it could get us into trouble.

When you began going to school in Győr, did the whole family move there with you?

No, I took the train, which definitely teaches a child discipline. I wasn’t particularly scattered-brained, but I was overwhelmed. My mother didn't say negative things to me except that, “child, you don’t have a good memory, you can only be an artist, not a doctor.” She didn’t know how emotionally burdensome it was for a child to help her helpless father every day, help wash his half-dead, waxy body. I had to overcome the repulsion that children viscerally have for disease and old age. She didn’t know how much self-discipline this took and how much it affected my memory as well. If mom had given up and committed suicide, I would have had two younger siblings who I would have had to raise. I was terribly afraid of that. It wasn’t until much, much later, when I was writing my short stories about this period, that all this came to my mind again.

I remember that I had a middle alto voice and was delighted when I was accepted into the choir. Then they heard me singing out of tune and sent me away, even though I loved it. I remember the drawing classes most clearly from this period. Leó Békési, László Alekszovics and the painter from Győr, István Tóvári-Tóth, who always took his “ten” children with him in a small cart when he went to paint. I knew as a child that I would never have kids and I would never drag them along with me when I went to paint. I felt sorry for my mother, too, for not being able to do what she wanted. She loved to write and read, but instead she was raising children at home and at school.

Did secondary school signify an important of change?

It was a completely different world. Female self-awareness develops in adolescence. They try to suppress it at the root with prohibitions and discipline, how one should sit, don’t put your legs apart, don’t do this, don’t do that… I wasn’t disciplined, I behaved very ladylike on my own. We had a sailor uniform in the girls’ secondary school, and we did everything we could to decorate ourselves in some way, although I looked like a little girl even at the age of eighteen. I was enrolled in a dance school, and all the boys wanted to dance with me because there was “something special” in me, but I didn’t let them get close to me. I had wanted to attend the Benedictine grammar school. They had a beautiful library that we were able to use. In the diocese of Győr, the Canon Somogyi[2] also tended to us, and he even allowed me to study art history in his library (I was the only girl who was permitted to visit the library to look at books).

The rural intelligentsia joined forces to make sure children would not be neglected. I remember the amazing furniture, which I loved to stroke, and the books, which had a sheet of tracing paper in front of each reproduction that one had to lift up. I was mesmerised by lithographs and fantastic paintings.

I wasn’t certain that I wanted to do this my whole life, but it was finally something beautiful that was meaningful to study. At school, we were taught that we don’t have to remember things, while Benedictine high school students had to learn a lot of things by heart. That’s what I wanted: I wanted to know everything, factually and data-wise. In the middle of Győr one finds the Benedictine church, next to the library and the school. I also liked the boys attending the Benedictine school. They were beautiful, muscular, confident, not as sloppy as the boys at Révai. There was a boy among them with whom I was in love, a tall, smart, handsome boy, his name was Feri. I always tried to be next to him, but he didn't really notice. How fortuitous that it happened that way. When I looked him up later, it turned out he had become a pharmacist.

Anyway, everything regarding sexuality has changed.

I would like to return to one of my childhood experiences, from when I was ten. To the experience of a drop of water, which I wrote as a short story. In the bathroom, we only lit the stove on weekends, and then we bathed in the tub one after the other because there wasn’t a lot of hot water. One morning, I was standing in the cold bathroom naked to the waist in front of the washbasin in which we were washing, and the water was cold too. A drop of water broke loose on my back, and the little time it took to trickle down my back, a fraction of a minute perhaps, suddenly seemed very long. It gave me such a feeling of excitement that I thought about the sensation, and that was the first time that I thought I was a unique person and that was such an unusual feeling that I should devote my life to it. It was only much later that I was able to determine what it was.

At that time, when I was in secondary school, we could not have sex openly, there was a lot of fuss about the whole thing. I lost my virginity at the age of seventeen perhaps, but I was only in love once. I didn’t go out with boys, I didn’t have a lot of sexual partners. Then I married relatively early, but only so we could sleep together, because the institution of marriage did not interest me then either, much as it has never interested me since.

But that drop of water was the key to the feeling, and back then it preoccupied me a lot.

Lacan and, before him, Freud describe this feeling of jouissance, pleasure and its possible cause very precisely. Perhaps it was this bodily feeling that led me deep into art. At the time, I didn’t know how I was going to express it. I had to wait a long time for that moment to come. Perhaps it was animation that was my first attempt at this, but maybe I should look at my old drawings to see how I tried to approach this kind of corporality.

Was this a conscious goal of yours all along? To keep the experience alive so that you could later capture it?

There was a time when I didn’t think about it, I forgot about it. I was a very good student, I wanted to learn everything. Learning is an exercise in which you learn what is written down, you don’t express what you feel. I wanted to be all-knowing, all-seeing, and all-feeling – that was my ambition from the age of ten.

When you graduated, did you already know where you wanted to go afterwards?

Yes, I had prepared systematically for this career path ever since I had begun regularly attending drawing classes. For six years, I spent two or three afternoons a week there from 6:00 to 8:00. I met my first husband there, too. The other important thing was the theatre and the opera, which I could go to in Győr, because we didn’t travel to Pest. And we read a lot. Not children’s books, everyone looked down on storybooks, much as we looked down on children’s games. At the age of ten, I read War and Peace, Anna Karenina, only adult books. And at the age of twelve I read Madame Bovary – these female figures became very important to me. But I also remember László Németh’s Égető Eszter and the writings of Margit Kaffka. The whole family, incidentally, was a fan of Margit Kaffka, she was the first feminist appreciated by Ady. “Let us be glad that feminism has arrived in Hungary," he wrote in praise of Margit Kaffka in the journal Nyugat. We had a copy of this issue and a few issues from the journal Woman and Society. My mother considered this important. I really liked the short stories by Margit Kaffka. Colours and Years was too complicated for me back then, I didn’t understand women’s pains yet, but I saw what was happening to my mother. She could have been easy prey, and she longed for love as a young widow, but she promised my father at his grave that she would not encumber their children with a stepfather.

She sewed us a raw silk dress with a black velvet stripe for the funeral. It was beautiful, and the touch of silk was so soothing. In any case, we were horrified by this vow. Many people courted my mother, and I also saw that she was in love many times, but whether she went so far as to have a sexual relationship with any of them, I don’t know. And I didn’t have a chance to ask later.

In 1956, after the death of my father, György Borsodi, who was a high-ranking military officer before the war and a handsome man and who emigrated during the revolution, asked for her hand. I really wanted him to be my second father, but my mother turned him down. She didn’t go to the West with him. When the prison in Győr was opened, where half of our relatives had been held as political prisoners, everyone set off for the border. They just kissed their relatives goodbye and left the country through the swampy part of Lake Fertő (Neusiedler See). We watched as our acquaintances, our friends, who not long ago had sat at our table reciting Ady, left. I still cry when I think about it. We cried then too. Mother locked us in the apartment, only once did we manage to escape through the window to see what was happening in the world. She had to teach. In any case, Borsodi had wanted to go to England with her. He reached England and then Alaska, from where our first IKKA[3] packages arrived.

Back then, those who had fled were able, after a while, to send packages to their families. We got clothes from him that could only be seen in Hollywood movies. At the time, we saw Mari Törőcsik in films, and she did not resemble Hollywood beauties. Thus, it was easy for me - because this gave me confidence. Teenage girls today, poor things, are forced to measure themselves against exquisite beauties, undoubtedly it is much harder for them. So, receiving these clothes was a miracle. It reminds me of a performance: in the winter of 1956 or 1957, in Abda, so in the village, the children went from house to house performing the Nativity scene and in exchange they were given pastries, strudel, Christmas candy or money. I also wanted to go, and I arranged it so I could join them, but only so that I could play the part of the Virgin Mary and wear the beautiful, shiny silk robe that only someone like Katalin Karády could have worn. I pestered my mother to death to alter it for me. It was thick white silk. Only white silk is beautiful to me. Like light in Baroque paintings. I remember it was tight around my slender waist, and I marched proudly in it because we did it with great solemnity. The boys carried the manger, which they had made at school, but I really only remember my own role and my clothes. Afterwards, I played theatre in this white silk dress for a long time, and they sat on the stairs and watched from there.

We were talking about how you prepared systematically for your career. How did your university entrance exam go?

At that time, people from the rural towns and villages were all called peasants by some of the people living Budapest. My mother raised me to have respect for peasants, and I found it offensive that someone would look down on them. As for someone living in the countryside, it was difficult to get accepted to the Academy. By then, I was a married woman. László Szombathelyi, my husband, was two years older than me. We applied together, but they didn’t accept us the first time around. Perhaps we may not have been able to prepare as effectively as fellow applicants living in Budapest who studied with Lajos Luzsicza in Fő Street.[4] I had nice but modest drawings, although I drew lines very purposefully, but the whole thing was not spectacular. My husband was facing having to enlist in the army, but just then the teacher training program of Szeged announced an additional opportunity for admission for people wanting to study Hungarian and drawing at a satellite location of the teachers’ training program. We quickly applied and were admitted, and so we studied in Szolnok for two years. In the third year, we were sent to Fegyvernek to teach in a school with twelve grades. They offered us a service apartment in the building of the day care, but we had to borrow money to buy furniture. That’s where we taught anyone in the village who was interested in learning how to paint and draw. Occasionally, we got party directives telling my husband to shave his beard and me not to wear miniskirts – the police sometimes looked through our curtainless windows to keep an eye on what was going on inside. I have a lot of stories from this time.

I looked very young as a teacher too, younger than my age, and the big failed teenage boys all sat in the back row. They ogled me. They wanted to embarrass me, but they themselves were also embarrassed. I taught drawing. There were objects which we could use as subjects for still lifes in the equipment room, including a skull. The boys said they had a better one at home and they would bring it in, and soon they showed up with two. I didn’t think twice about it until one day women came menacingly towards me across the schoolyard. They called me out and held me accountable, asking what I was thinking by encouraging the boys to rob graves. It turned out that the skulls had indeed been taken from the cemetery and then cooked in a cauldron at home. That had been their affectionate gift to me. I was very unprepared for the whole experience, this strange slice of reality, because until then, even if I didn’t necessarily live in a bubble, I still felt like I knew my place. In any event, at a certain moment we decided to lock up the apartment quickly, and we left all our belongings there, pocketed the key, and came to Budapest. All our belongings that we left were taken, our paintings, our furniture. But there was no other way of getting out of that situation.

The following year was terrible, we moved from sublet to sublet, until we finally rented a room in Téglagyár Square 3. Sometimes I went home late at night, once I even had to exchange blows, because some men wanted to rape me, this neighbourhood of Csepel was not safe. I taught at the school in Lenhossék Street, László made a living by working in a plastic moulding shop on Baross Street, but in the meantime, we also attended the drawing course held by Lajos Luzsicza.

It seemed that my teachers were in love with me and wanted to separate me from László, whom I considered much more talented than myself. But they saw the world from a phallic point of view, and I was absolutely aware of this and despised them for it. In Zebegény, the sculptor József Somogyi held a summer course, and he thought I was talented and beautiful (although he likened a woman’s butt to a horse’s ass). He said he would do everything to get me accepted to the Academy, but I stipulated that I would either go with my husband or not at all. He was very surprised by this, but in the end, László and I were both accepted that year. A nice circle of friends formed at Luzsicza’s, that’s where I met Péter Forgács, Tamás Eskulics, and Károly Kelemen. We went to parties together, to Kex concerts, also held in Fő utca. There was a lot of joie de vivre in the air, and I felt good, as I had always longed for precisely this freedom.

Whose class did you attend at the Academy? Who was your master teacher?

Szilárd Iván. I was accepted to the painting department, I transferred to the graphic arts department in my third year because I was badgered to death in the painting department. I couldn’t paint a Titian, I’ve been capricious, determined, and independent, since I was a child, but I also had more self-discipline, also due to my upbringing, than anyone around me. Few people were accepted, and the majority of my fellow students were from Budapest, and I was very hostile to the selection process. It was a privilege to attend the Academy, and from the very outset I was given a high scholarship because I almost always got straight A’s. I had a good visual memory, I remembered everything professor Krocsák[5] drew on the board in geometry class too. It killed the boys, who actually understood geometry. They were so envious.

I went to the blackboard, closed my eyes, and recalled how and where it was drawn on the board, where “a” had been, where the lines had run – I had memorized the whole thing as a fanciful composition (I didn’t understand it, I wasn’t really interested in it, only later did what I had learned there become important). I drew the lines, wrote the formulas, and didn’t even have to say anything because I was already given the highest mark. So, I was a good student. I would be sitting on the stairs at 7:00 in the morning, going in with the cleaners, and I was one of the last people to leave the building in the evening. For seven years I lived in Herman Ottó Street, in the dormitory of the Academy of Applied Arts, first in a room with seven others and then with three other people, while my husband was put in the dormitory on Budafoki Road. Our marriage was ruined. Despite my best efforts, I wasn’t able to get a simple apartment. Poverty mingled with extreme vulnerability.

I was a restless, girly character, but with a great sense of responsibility. András Halász always said that you can fool around with all the girls, except Orshi, because she supports herself and knows what she wants (incidentally, he was not a macho man in a bad sense). I attended the Academy for seven years while also working for Interpress.[6] At night, I drew and transferred Letraset letters to photos – if I remember correctly, I was paid one forint for every word, I saved money to buy an apartment to see if I could keep my life together. Meanwhile, the boys went off gallivanting and drinking – not that I never went along. Because I was also giddy and when I got paid at the end of the month and my pockets were full, I was my grandfather, the gentry, who generously threw money around – which the boys of course found attractive. I really liked spending money, so when I would go home, my mother immediately emptied my pockets and placed the money in a savings account in my name. She had remarried by then and had moved to Budapest while I had been living in a dormitory.

There was a lot of rivalry at the Academy. I was the first to receive the Béla Kondor scholarship, which was a large sum at the time, 1,000 forints monthly – and my scholarship was also that much. (By comparison, my mother, after forty years of teaching, made about 3,000 forints a month.)

Who were your classmates?

András Halász, Károly Kelemen, and Mariann Kiss in the graphic arts department, András Koncz, Gyuri Fazekas, Zsiga Károlyi, Dénes Bogdány, and Ernő Tolvaly in the painting department, Zuzu (Lóránt Méhes) in the restoration department. I felt that I had an affinity with Zsiga, as a student, perhaps because his father was disabled. He was a fragile student, but he became a tough adult. Ákos Birkás was older, he had graduated and was already teaching somewhere else when we went there. Deep friendships were formed.

This is the period of the Rose Café...

Yes, but also the period before it. The Rose grew out of these friendships.[7]

I have always felt, even in the case of the lodgings I was given at the dormitory, that someone was keeping an eye on me. This is discernible in my entire fate. I had enormous undertakings, some were even life-threatening, and somehow, I always managed to pull it off. I’m not afraid. As children, we were not allowed to be afraid, and we were not allowed to complain or cry either. “If you cry, no one will feel sorry for you, solve your own problem…” I didn’t have very many friends as a child, just some imaginary foreign friends under the burdock leaf with whom I chatted in Chinese and English. My mother would tell me while cooking, “But there was no one there, don’t you understand? Those are imaginary people ... why, you speak Chinese?” I argued with her and pretended to speak in a language. My contemporaries did not befriend me, in part because I was much more educated than them and in part because I had to behave like an adult from an early age. I did not play. And later, at the Academy, it was the same. I would get in with the boys and then fall back into my own role.

These relationships were very strange. Once, as I was going home alone at night, the boys followed me, and one of them grabbed me from behind, shook me and said “you're neither pretty nor smart, so what do they like in you?” I countered by saying, “but you’re also following me...” I think it was my determination that was appealing. Miklós Erdély also wanted to hook up with me in Szép Ilonka, he was in love with me for a long time. I think (but maybe I’m wrong) it was with him that I first went to see Béla Kondor, of whom he was a big fan. It must have been around 1972, Kondor was considered a very avant-garde figure at the time. He committed suicide while I was still in college. He was drunk, but he spoke fluently and cleverly about literature, books, and mythology, just like people in my family. He could have been a father figure. This pitiful, drunken talent lived in an inner world that was infinitely interesting. His art has since declined in value because his drawings can be very strongly tied to a style that was revered under socialism, the etching. When Erdély first came to see me at the Academy and I was making etchings, he said of mine that it was like they had been drawn by Béla Kondor. Erdély always knew how to stab someone in the heart –something that I latter labeled an avant-garde technique because from then on, a dialogue would begin, because whoever is stabbed in the heart is forced to explain him or herself. I myself never thought that my drawings had anything to do with Kondor.

There was a saying back then which I always just laughed at – that talented people didn’t have to work. My mother had told me that if you want to be an artist, you have to be famous, look in the encyclopaedia, that’s where the famous artists are. I was ten at the time. I looked in the art history book, which had been translated from German in the 1930s. It had beautiful pictures, but there were no women in it. Well, my mother said, then you have to work extra hard, because there’s another factor: you’re poor. That was a pretty good lesson.

So that’s where we were: Erdély likened my etchings to Kondor’s – a comparison which stabbed me in the heart – but that’s where our dialogue began. This really was everyone’s method this was the avant-garde macho method. To say “fuck the chicks” - that was the basic slogan, and that talented people didn’t have to work. I thought the opposite.

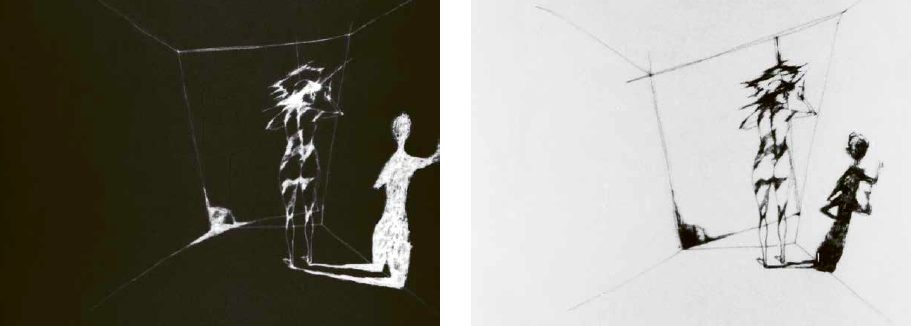

Things were slowly changing, but at the beginning, when Gábor Bódy and Erdély visited me in the studio, this was the general view. This was something that was taking form there, in that political environment, a kind of sabotage, self-sabotage – my hand-drawn animation The Line grew out of this friendship with Bódy. These were loves, or infatuations on their part. I’m talking about the school years of 1974/1975/1976.

Where was your studio at the time?

Károly Raszler thought I was talented, and so, together with Aladár Almásy (who was a year ahead of me), we were given a large studio, a room which is now used by twenty people. Imre Szemethy also came and worked there occasionally, but then he graduated. It was a large room with high ceilings, and the windows looked onto the Specialty Confectionary[8]. I loved working there. I made several hundred etchings there. My fingers were covered with acid, I smoked two cigarettes at once, not noticing that I hadn’t even put out the first one. I was pretty giddy and probably extremely exhausted too, because for about ten years I just gutted myself. I slept for three or four hours a day, just so I could fit everything into my day. It must have been visible at the time.

Tell me a little about Bódy. How did the two of you meet?

He was a magical personality. He was the genius on duty, everyone looked at him that way. He was beautiful and ugly at the same time – like the devil. A beautiful devil. He was full of evil energy. Beauty, compassion, and judgment were in an eternal struggle inside him.

We went all over the place. When he started filming American Anzix in 1975, he came into the dormitory at night and fell asleep drunk in the bathroom, under the shower. He had waited for me to wake up, but the girls had closed the door in order to let me sleep for at least three hours after transferring letters. For fun, we went to the Budapest Hotel, the Circular Hotel, many times, which had a café at the top. And mainly to the Young Artists’ Club, then to house parties, Kex concerts, performances, lectures on semiotics by János Zsilka, and the movies. At that time, nothing seemed expensive, and compared with the others, I always had money.

I greatly admired Miklós Erdély, who lived in amazing luxury. He was smart, he had a nice garden, a beautiful house, and he could travel abroad - but that was an exception then. Bódy lived in poverty, almost like me, alternately moving in with his mother or with his father. But Erdély was an old man, while Bódy and I were contemporaries and I was happy to hang out with him. I didn’t think of the two of us as a couple, we were friends, but every moment was enjoyable with him. He was making his Film Language series for television at the time. He asked me too to do the drawing for one of them, but the etching technique I used interested and irritated him at the same time. The copper plate was covered with soot and the lines were etched into that.

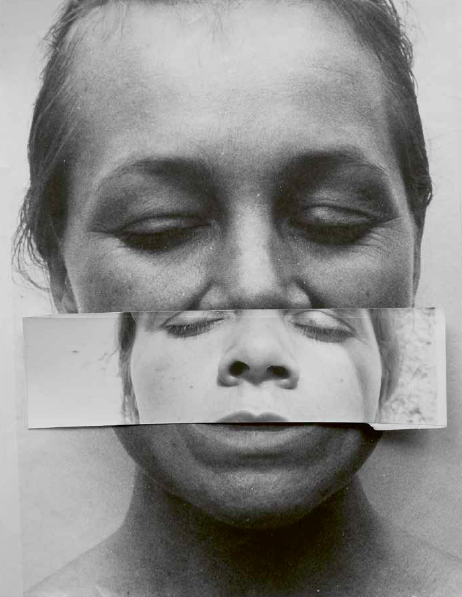

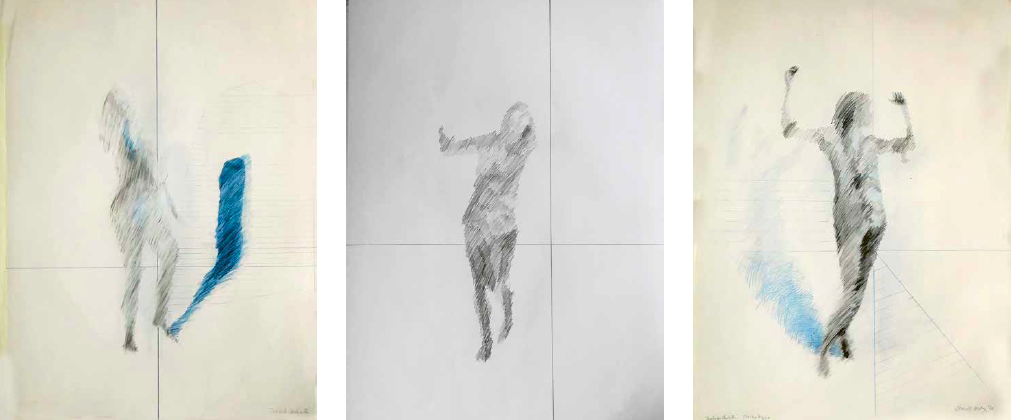

In his 1976 series on the language of film,[9] my animation The Line, which I drew in the style of an etching, similarly to a line etched into the film, appears in connection with the technique of photogram. It was my idea to turn the drawings from negative to positive. By then, I was already enlarging my photos at the Academy in the lab of the graphic designer students, and I was interested in the relationship between the negative film and positive image. No one understood what I was doing, but this has been the case since I was a child, I am used to keeping my ideas to myself. People around me could only see the technique, they had no inkling of the meaning. They did not connect it with feminism or Valéria Dienes, Margit Kaffka, Madame Bovary, or Simone de Beauvoir – whose books I had read, as my mother had copies of them. Something was starting to stir a little again – but the proponents of the feminism that existed in Hungary between the two world wars were considered class enemies, and the feminism itself was seen as a middle-class, bourgeois thing at the time and thus was censored. At the same time, it was very good that there was a kind of political program of equality between the sexes , social equality that was taught, and that everyone knew, but it was not really built into practice. At the Academy, only the sports teacher and Russian language teacher were women. Most women at the time, who had aspirations for a career and had strong egos, cultivated a male ego within themselves. As far as I recall, more than anything, they looked down on feminism.

Erzsébet Schaár and Piroska Szántó were present and were politically supported as female artists. Erzsébet Schaár was important for me. But they were more like women artists and not “feminists,” like Valéria Dienes in dance, who had emphasized the differences between the sexes, in the ways of thinking, producing and in the manners of expressing themselves.

How did your relationship with moving and showing your body begin? How did the idea to use your body occur to you?

After the water drop experience, through my acting performances in my childhood and then when drawing female nudes, I realized that everything I drew resembled me. Every woman I drew looked like me. My body looked like theirs. But I was prepared for this by my readings. If you read Margit Kaffka as a teenager, you know that women think and feel differently.

But to start showing your own naked body, that was a big leap from this, to stand there naked yourself ...

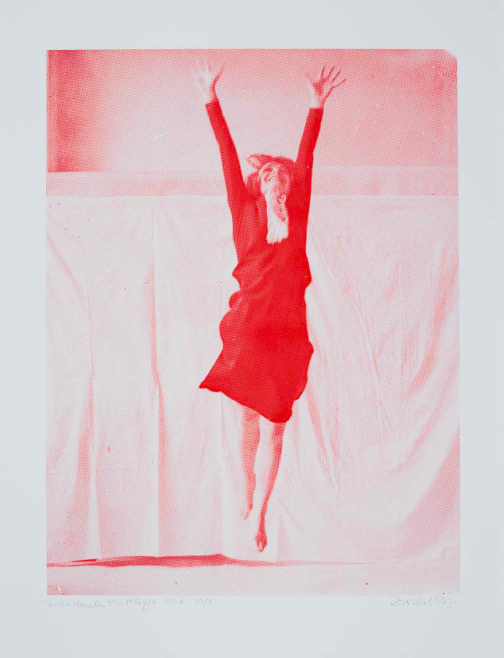

Two things contributed to this. One was that in 1975 I started photographing, the photographs of the nude model studies in the library of the Fine Arts Academy’s archive, and I prepared them to exhibit. (I only partly succeeded in doing this because you weren’t allowed to use photos in the graphics department.) I printed the photos myself and used them as my own photos. The other series I had prepared that year I also photographed at the library of the Academy, I photographed photos of free dancers, which I collected, researched , and also exhibited. I had the negatives developed and did the printing myself in the photo lab of the applied graphics department.

I studied semiotics in the Hungarian Department during my linguistic studies, more precisely, the instruction of Hungarian linguistic studies was based on semiotics. Gábor Bódy also adopted this approach. This was incorporated into my critical analytic feminist method, in my search for meaning, the relationship between the signifier and the signified was very important. That’s why I started working with photos, and I discovered the same thing when drawing nudes, that they all looked like self-portraits, that every drawing looked more like me than the model. I drew myself as self-portraits of my psychological states in my etchings. Even if they resembled Kondor’s drawings and etching techniques, compositions, my intention was very different, he created mythology, while I expressed my own emotional story in my etchings.

In 1975, Iván Vitányi did an interview with Valéria Dienes[10], after the first conference on semiotics was held in Hungary, in Tihany and Valeria Dienes participated as a lecturer on semiotic studies. For the first or second occasion, Umberto Eco was even invited, about whom I already knew that he connected philosophy with semiotics. I truly believed that the search for meaning and reading signs connected to a philosophy. In my feminism, I meant to raise emotions to a philosophical level, and semiotics was the key to this. But this wasn’t just in my head. Now, when I watch the Bódy film again, in the section when he talks about media, the interoperability between media, it’s as if I were listening to myself. Maybe we all heard these ideas together back then, we went to a lot of places together. He took me to György Lukács's apartment too. Bódy was a magical figure. He was in a rivalry with everything, everyone, philosophers, artists. Once, after he had just returned from England, he howled in front of the dormitory, like a wolf. I instantly recognized his voice. He wanted to discuss how he wanted to be like Fassbinder, enthusiastically recounting what Fassbinder was doing. This was already in 1976, when I participated with my animated drawings, in his educational TV film. We read Heidegger in a Marxist critical edition, but we crossed out the critical dogma and read only the quotes from the original text. And we read Wittgenstein, too.

Which of the people who were artists, strictly speaking, did you respect at the time?

Valéria Tóth. You don't know who she is, do you? I don't know what happened to her. She was a wonderful painter. Like me, she also went to Iván Szilárd’s class in the Painting Department. She had a strong sense of the personal, the female point of view like me. Her colours ... but everything she did made me swoon. I stood behind her and thought how amazingly talented she was and that I was not like her. But I also thought that I was going to make it and she couldn’t. There is fragility in every born talent (especially in women). My theory is that secondary talents pursue careers because they want to make up for something. Those whom I saw as being very talented when I was young have (almost) all disappeared. Even now, I have friends who I consider super talented, and I think what a shame that she’s raising a child. In order to have a career in art, one must work hard and in a focussed manner – my mother told me that when I was ten years old – you have to be in the art history books. I haven’t forgotten that.

I would like to return to the question we have deviated from, that is, what was the push that made you turn to your own body as a medium after making etchings?

Do you mean the performances? Yes, that's why I mentioned Valéria Dienes. I learned about her lectures on orchestics, choreography of dance movements from the aforementioned Vitányi interview. The fact that a philosopher-mathematician was both a semiotic linguist and a free dance choreographer and teacher and a movement-school founder - that blew me away. I was so angry at the world that this genius was censored and only rediscovered in Hungary at the age of 94-96. How could she have been forgotten for so long? Will this be my fate too? I immediately went to see her so I could learn everything I could from her. Philosophers say that you can only learn what you already know. What she told me then I already knew at the level of intuitions, conjecture, but the way she was able to put it all together gave me incredible support. That was the moment when I was able to connect the feeling of the water drop running down my back to what she knew. That she connected philosophy with orchestics. Connecting feelings to intellect. Body to consciousness.

Her husband had simply left her with the children for one of his students. I had a very strong compassion for women – but I am especially able to relate to self-fulfilling, talented women.

That year, I also saw a film about Isadora Duncan which made me realize that this was my destiny. In the film, there is a scene in which she dances half naked in front of Russian soldiers. One can imagine these poor Russian boys being locked up in an institution with all their sexual fantasies, banging their heads against a wall or I don’t know what they were doing to lower their testosterone levels. And then there’s this beautiful woman (who wasn’t actually as beautiful as she was passionate), it was a sexual provocation in and of itself. But it wasn’t the challenge that unfolded in this scene that caught my attention, but the self-awareness, the very deep bodily self-awareness that revealed itself in her body. I was convinced that the basis of feminism was free dance, and I based my own feminism on that as well. But it is not dance, or performance, but the liberation of the body that matters, and it is this level of body awareness from which art can be made. I knew this already, but in 1975 – I always say that I am an artist with a destiny - when I was just about to make all this into art, it was inspirational, and it gave me a strong boost. Examples, role models for performance. (Which was also called body art at the time.) My greatest inspiration, my ideal was my mother, but these women were brilliant, and I regret that my mother was not able to accomplish what she wanted to achieve. But that was a different time.

[1] In August 1945, Benes issued a constitutional decree on the revision of Czechoslovak state citizenship for persons of German and Hungarian ethnicity, denying them citizenship. Their property was confiscated and they were forced to leave with nothing more than a suitcase weighing no more than 25 kilograms.

[2] Antal Somogyi, Abda, 1892 - Győr, 1971, Catholic priest, art historian, private university teacher

[4] Today: Ferenczy Visual Workshop

[5] Emil Krocsák was head of the Academy’s geometry department until 1975

[6] Interpress Publishing and Printing Company

[7] The name Rose Circle refers to a group of artists who attended the Academy of Fine Arts in the first half of the 1970s, as well as other youths with an avant-garde mindset who joined them and who were active participants in fluxus experimental? conceptual? exhibitions hosted at the nearby Rose Café and other similar venues in 1975 and 1976.

[8] It went by this name at the time. Before and after this, it was called the Lukács Confectionary. Later it was purchased by a bank which doesn’t run it anymore.

[9] Film School 3/1: On the Tools of Film and Photography, Hungarian Television, 1976

[10] Valóság [Reality], issue 1975/8

The translation of this article was created with the support of Summa Artium.