„...engem sohasem zavart, hogy gyerekként nem ihattam Coca-Colát” // '...it did not really bother me that we did not have Coca-Cola'

Interjú Ciprian Mureşannal

Ciprian Mureşan: Magam ellen tüntetek, 2011. HD videó, 30’ 35” (társszerző: Gianina Carbunariu) Fotó: Ludwig Múzeum

Ciprian Mureşan: Magam ellen tüntetek, 2011. HD videó, 30’ 35” (társszerző: Gianina Carbunariu) Fotó: Ludwig Múzeum

// FOR ENGLISH PLEASE SCROLL DOWN //

Kezdjük az elején! Tizenkét éves voltál a romániai forradalom idején, tehát a korai kamaszkorod legelején egy jelentős változás történt az életedben. Mik azok a gyakorlatok, amelyekkel művészként a szocialista múltat kezeled?

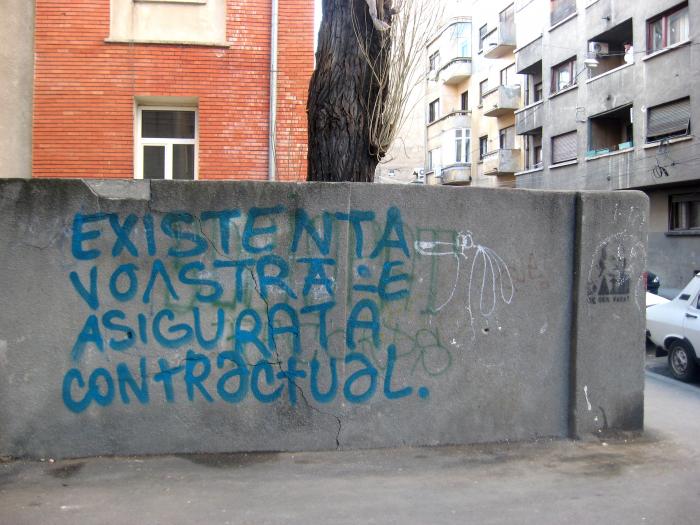

Ennyi idősen az ember még nem úgy érzékeli a változást, szerintem mindenkinek jó gyerekkori emlékei vannak, például engem sohasem zavart, hogy gyerekként nem ihattam Coca-Colát. Magamat egy olyan nemzedék részének tartom, amelynek tagjai a rendszerváltás előtt még gyerekek, 1989-ben igazi tinédzserek voltak, később pedig ők lettek az MTV-generáció. Ez azért fontos, mert az idősebb korosztályok tagjaival ellentétben én megfelelő távolságból, tudom kezelni ezt az időszakot, meglehetősen függetlenül. Az átmeneti jelző, amit olyan gyakran használnak ennek az időszaknak a leírására, azt sugallja, mintha valami rosszból a jó útra tértünk volna, pedig hát tudjuk, hogy ez messze nem volt ilyen fekete-fehér. De akárhogy is nézzük meghatározó része lett az életemnek. 1989 után olyan témák lettek aktuálisak, mint az ébredő nacionalizmus vagy a fokozott érdeklődés a vallás iránt. Ezek mellett fontos volt az is, hogy már középiskolásan is képzőművészetibe jártam, majd jött az egyetem, és foglalkoznom kellett az egzisztenciámmal is, azzal, hogy mint művész hogyan tudok túlélni. Egyik témámat sem én választottam, ezekkel egyszerűen foglalkozni kellett, beleszülettem. Az egyetemen, a kilencvenes évek végén sok mindenkit vonzott a DJ-k, a VJ-k és a design világa, de ezek a témák jellemzően importált karakterük miatt nem váltak a munkáim részeivé.

Itt a Ludwig Múzeumban is számos olyan munkádat láthatjuk, amelyek a szocialista múlttal foglalkoznak.

Már az egyetemen kaotikus volt a helyzet: az 1989 előtti értékrend szinte nevetséges ellentétben áll a beaux arts-éval. Voltak jó tanulók, akik napi szinten félrevezetődtek, hiszen az, amit az oktatóktól hallottak egészen más volt, mint amiket a külföldi könyvekben, katalógusokban és magazinokban láttunk. Ezzel a káosszal, ezzel az űrrel kezdtem el foglalkozni a Leap into the Void, after 3 seconds című munkámban Yves Klein nyomán. Ez a mű egy ablakból kiugró művészt mutat a levegőben lebegés pillanatában. Az én verziómban az eredeti jelenetet három másodperccel később mutattam be, azaz a művész - vagyis én - már nem az ég és föld között lebegek, hanem a járdának csapódok, eléggé drámaian mutatva a 2004 körüli időszak körülményeit. Ez az űr érzékelhető volt a nemlétező román művészeti szcénában, akkoriban egyik évről a másikra számos román művészeti intézmény szűnt meg és tűnt el. A Romániai Képzőművészek Szövetségének galériáját becsukták, mert privatizálták az épületét, visszaadva eredeti tulajdonosának. A Szövetségnek volt egy másik kisebb galériája is, amelynek megváltoztatták a profilját és ajándékbolt lett belőle. Egyik nap még jó kiállításoknak adott helyet, másnap már szuveníreket árult. Ez az instabil periódus nem sokkal azután volt, hogy végeztem az egyetemen.

Ciprian Mureşan: Cím nélkül (Mikulás), 2010. Videó, 13' 42'' Fotó: Ludwig Múzeum

Ideológiai témákkal is gyakran foglalkozol, a Cím nélkül (Mikulás) elnevezésű videómunkádban tükröt tartasz az intenzív vallási elköteleződésnek. Miért épp az irónia és a humor eszközeivel ragadtad meg ezt a mindig is kényes témát?

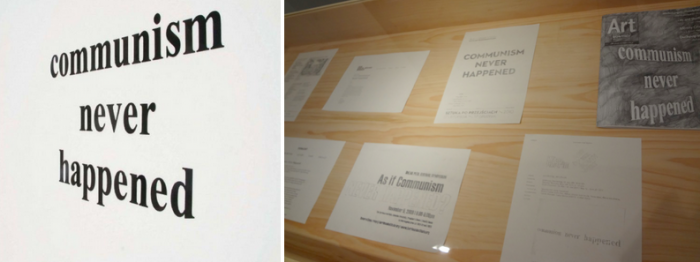

Romániában az emberek vallásosak, de nem radikálisan. Nagyon ironikusnak találtam azt, ahogy 1989 után épphogy megszabadultak Ceaușescu teljesen abszurd ideológiájától, máris ráfüggeszkedtek a vallásra. Ugyanekkor vezették be a vallásoktatást az iskolákban, a darwinizmust pedig törölték a tantervből. Tényleg mindenki a vallás felé fordult, a teológiai tanszék is hirtelen nagyon népszerű lett. Mivel az ortodox papok szakállt viselnek, a forradalom után nagyon sok szakállas pap tűnt fel, és a szakáll ikonikussá vált. A Mikulás szakállához pedig mindenki tud kapcsolódni. Ez egy nagyon fontos videó volt számunkra, egyáltalán nem paródiának szántuk. Ez volt az én reakcióm az egyház növekvő szerepére. Jól mutatja a korszak szellemét, hogy a pap szerepére felkért színész – a többi szerepet a barátaim játszották – rossz lelkiismerettől vezérelve gyónni akart menni egy pap barátomhoz a forgatás után. Ciprian Mureşan: Communism Never Happened, 2006 Fotó: Ludwig Múzeum

Ciprian Mureşan: Communism Never Happened, 2006 Fotó: Ludwig Múzeum

Ciprian Mureşan Communism Never Happened című munkája a 2014-es Art Basel Miamin Fotó: Ruxanda Renita

Az egyik rajzsorozatodat nemrégiben az Art Basel Miami vásáron is bemutatták, ez gyakorlatilag a Communism Never Happened című munkád utóéletének ceruzarajz-archívuma. A 2006-os mű betűelmeit propaganda-hanglemezekből vágtad ki. A Communism Never Happened számos kiállításon szerepelt, valamint különböző kiállítások, konferenciák vagy szövegek emelték címükké.

A sorozat kronologikusan mutatja be azt a Kelet-Európában jellemző kortárs képzőművészeti vitát, amelyben a művész múlthoz való viszonya a téma, valamint újraértelmezi a különbséget a kommunizmus – mint egy jobb társadalom ígérete – és a különböző, 1989 után létrejött politikai berendezkedések között. Ezzel a munkával az eredeti művemhez fűződő tapasztalataimat akartam megmutatni, és az összes reakciót, amelyet az a megjelenésével kiváltott. Első alkalommal Varsóban mutattam be. Már ott, a második napon eltűnt a sarló és a kalapács, Prágában pedig valaki eltulajdonította a never szó kezdőbetűjét, (így lett belőle ever). Öt kurátor is a Communism Never Happened-öt akarta a kiállítása címeként használni. Ebben a három vitrinben ezeket próbáltam ceruzával dokumentálni. Eredetileg a valódi dokumentumokat terveztem kiállítani, de aztán meggondoltam magam és a ceruzamásolatok mellett döntöttem, mert így én is manipulálni tudtam, én magam is be tudtam avatkozni a saját projektembe egy kicsit. Az eredeti munka 2006-os, szóval nem telt el olyan sok idő, mégis jó érzés volt újra foglalkozni vele.

Hogyan reagált minderre a miami közönség, és úgy általában miben különbözik a munkáid fogadtatása a kelet-európai régión belül és kívül?

A vásárok mindig elég furcsák, különösen Miamiban. A David Nolan Galéria jelentkezett ezzel a projekttel, ők ott visszatérő kiállítók, ezért egy plusz szekcióval is bírtak. Ez az archívum már régóta benne volt a fejemben, és a vásár jó alkalomnak tűnt arra, hogy meg is valósítsam. Ami a munkáim fogadtatását illeti, úgy vélem ez többé-kevésbé mindenhol egyforma, de természetesen vannak dolgok, amiket mi sem tudunk az USA-ról és vica versa. Ha nem ismerik a kontextust, az teret ad a szabad interpretációnak. Én kifejezetten szeretem, ha a nézők ebben teljes szabadságot kapnak és semmi kapaszkodót. A Communism Never Happened munkám nagyon sokféleképpen lett értelmezve; volt amikor megkérdezték, hogy ezzel azt akarom-e mondani, hogy el akarjuk felejteni és új életet akarunk kezdeni. De például Tamás Gáspár Miklós szó szerint vette, minthogy a kommunizmus valójában sosem létezett, ti. a gyakorlatban nem az eredeti elképzelés valósult meg, a létező szocializmust leginkább államkapitalizmusként értékelhetjük. Ahogy te is említetted, a betűket egy olyan hanglemezről vágtam ki, amelyen a Ceaușescu-időkben népszerű kommunista fesztivál dalai voltak. Ez a kulturális produktum jól tükrözi a korszakot, azt hogy az egésznek igazából semmi köze sem volt a kommunizmushoz, ezek inkább nemzeti események voltak. Szóval ezért választottam ezt a lemezt.

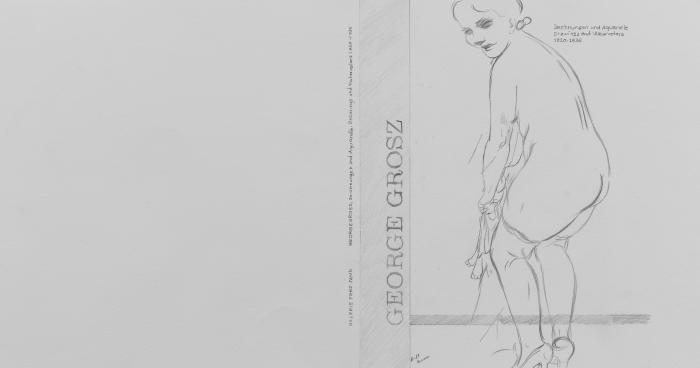

Ciprian Mureşan: Cím nélkül (George Grosz könyv), 2012, grafit, papír, könyvként kötve 26,7 x 22,5 x 2 cm Fotó: Ludwig Múzeum

A korai alkotói periódusodban gyakran készítettél videókat, ehhez képest a legutóbbi időszakot olyan munkák jellemzik, amelyeket manuálisan hozol létre, leginkább ceruzarajzok ezek.

A legutóbbi munkáim az európai és nyugati ikonográfiai hagyományból merítenek. A reneszánsz idejéből másoltam katalógusokat a saját kezemmel, ceruzával, mert többet akartam rajzolni. Újra manuális akartam lenni, és napi feladattá tenni a munkámat. Mára napi gyakorlattá vált, hogy precízen másoljam le minden nap például Pierro della Francesca vagy Vermeer vagy más, általam kedvelt művész munkáit. Eleinte csak kopíroztam, de aztán elkezdtem felfedezni, kibővíteni és továbbgondolni ezeket a ceruzarajzokat.

Itt van például egy ilyen munkám, George Grosz könyvének a másolata, amely úgy van kötve, hogy magukat a rajzokat nem láthatjuk, vagy itt felettünk egy Warhol-katalógus alapján készült munkám, amelynek minden képét egyetlen lapra másoltam. Mostanában sorozatokban gondolkodom, mert ahogy mondtam, igyekszem a rajzolást rendszeres, napi feladattá tenni.

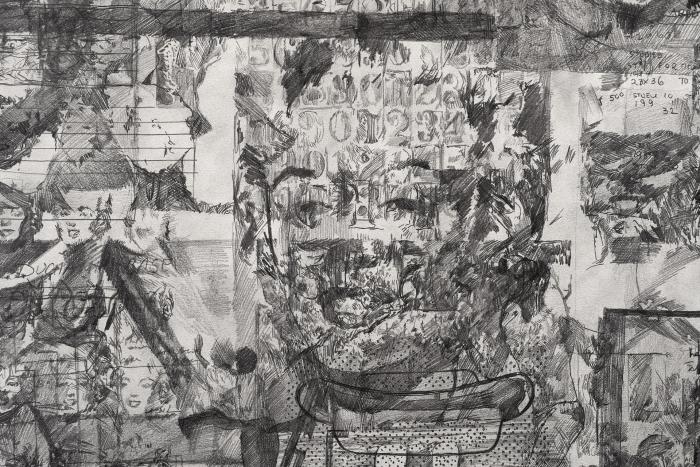

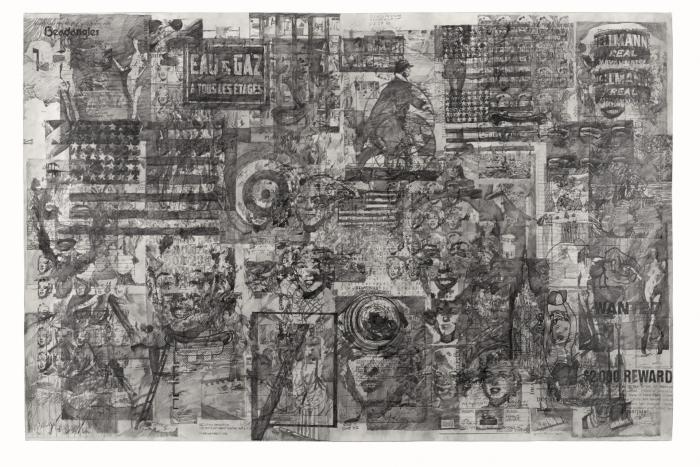

Ciprian Mureşan: Elaine Sturtevant könyvének minden oldala (részlet), 2014, papír, ceruza, 93 x 142 cm

Mi a motivációja ennek a módszernek? Ez a te saját válaszod a képek túlburjánzására?

Ez az egész másolási és rajzolási mánia abból a tényből fakad, hogy szó szerint elárasztanak minket a képek és a katalógusok. Szükségesnek tartottam, hogy újratöltekezzem. Nem olyan régen még hatalmas dolognak számított, ha a birtokodba került egy katalógus, vagy akár csak egy képregény. Emlékszem mennyire belelkesültem például, amikor még Nagyváradon éltem és a magyar barátoktól olyan képregények érkeztek Magyarországról, melyek nálunk egyáltalán nem voltak elérhetőek. Ugyanez volt a helyzet a művészeti albumokkal is, nagyon ritkák voltak, és így az információ és maguk a képek is nagyon lassan terjedtek. Emlékszem még azokra az időkre, amikor Antik Sándor nagy privilégiuma volt egy Joseph Beuys-katalógus, vagy az hogy mekkora szám volt, ha valaki jól informált lehetett a bécsi aktivizmusról és Hermann Nitsch-ről. Ma a helyzet teljesen más. Nekem ez az egész munkamódszer arról szól, hogy felfrissüljek ebből a bulimikus képfogyasztásból. Nem akarom, hogy a képek a laptopom memóriájában legyenek csak rögzítve, szeretném, hogy átmenjenek az ereimen és a kezemen is, és így a saját módomon tudjam feldolgozni őket.

Ciprian Mureşan: Holt terhek (Dead Weights) a Folyamatos múlt című kiállításon a Fészek Művészklubban, 2014 Fotó: Simon Zsuzsanna

Tavaly szintén Budapesten állítottál ki a Folyamatos múlt című csoportos kiállításon, amely a szocializmus kulturális hagyatékára reagáló kortárs műveket mutatott be.

Igen, a Holt terhek (Dead Weights) című munkámat választotta ki a kurátorcsoport. Az installáció részét képező, nyomónehezékként használt gipszszobrok eredetijeit egy raktárban tárolták Kolozsvárott, itt találtam rájuk. Különböző stílusúak voltak: az egészen régiektől kezdve a szinte absztraktig, teljesen random módon válogattam őket a húszas évektől a nyolcvanasig, így egy igazi stíluskeverék jött létre, amelyben ugyanúgy megtalálhatók a szocreál szobrok, mint a Nyugatot utánzók is. Ezeknek a gipszmásolatait Bázelben is bemutattam, de nem hiszem, hogy bárki is értette volna őket, mert nekik csak valami ismerős dologra hasonlítottak, érdemben nem tudtak viszonyulni hozzá. Itt Budapesten viszont jól illeszkedett a kiállításba. Kiállításmegnyitó Fotó: Ludwig Múzeum - Kortárs Művészeti Múzeum - Glódi Balázs

Kiállításmegnyitó Fotó: Ludwig Múzeum - Kortárs Művészeti Múzeum - Glódi Balázs

Mennyire ismered a magyar művészeti közeget, az aktuális magyar kultúrpolitikai témákat?

Követem a magyar művészeti szcénát, és képben vagyok az itt születő művekkel, ezek közül legjobban Kis Varsó, Erhardt Miklós, El-Hassan Róza és Maurer Dóra munkáit ismerem. Miklóssal jó barátok vagyunk, és több kiállításunk is volt együtt, Iasiban és Kolozsvárott is.

Követem a fontosabb magyar eseményeket is. Az én érvem a Ludwig Múzeumbeli kiállítási lehetőség elfogadása mellett az, hogy Szipőcs Krisztina kurátort régóta ismerem. Talán azt mondhatom, hogy belülről is lehet ellenállni, nem kell úgy tenni, mintha érvényesítenénk a hivatalos politikát.

Ciprian Mureșan Fotó: Ludwig Múzeum - Kortárs Művészeti Múzeum - Glódi Balázs

Ciprian Mureșan (sz. 1977) Kolozsváron él és dolgozik; 2005 óta az IDEA art + society magazin szerkesztője. 2014-ben vendégelőadó volt a braunschweigi Hochschule für Bildende Künstén. Legújabb egyéni kiállításai: Obstacle Racing, Hochschule für Bildende Künste Braunschweig (2014); Stage and Twist (Anna Molskával együtt), Tate Modern, London (2012); Recycled Playground, több helyszínen – FRAC Champagne-Ardenne, Reims (2011), Centre d'art contemporaine, Genf (2012), Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver (2013), n.b.k. - Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Berlin (2010) – bemutatott vándorkiállítás. Válogatott csoportos kiállítások: Six Lines of Flight: Shifting Geographies in Contemporary Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Sounds Like Silence, Hartware MedienKunstVerein (HMKV), Dortmund; A hang szabadsága. John Cage a vasfüggöny mögött, Ludwig Múzeum, Budapest (2012), Les Promesses du passé, Centre Pompidou, Musée National d´Art Moderne, Paris (2010); The Generational: Younger Than Jesus, New Museum, New York; The Seductiveness of the Interval, Román pavilon, 53. Velencei Biennále (2009).

Kapcsolódó tartalmak:

Folyamatos múlt - Kortárs reflexiók a szocializmus kulturális hagyatékára

Artmagazin Videóblog

//

Let’s start with the very beginning, you were 12 at the time of the revolution in Romania, so you were in your early adolescence years when you experienced a major change to which you are still reacting. What are the ways you usually handle the socialist past? Can it be regarded as a continuous theme source?

Ciprian Mureşan: Auto-da-Fé 1, 2008 (detail),C-Print, 154 photos, 50 x 37.5 each Photo: Ludwig Museum - Museum of Contemporary Art

At the exhibition here in Ludwig there are several works dealing with the communist past. What is your artistic practice to approach these issues?

Already at the art university I noticed a chaotic situation: the old system of values valid before 1989 and that of the beaux arts were clashing to kind of a funny extent. There were good students at the university but they were all disorientated on a daily basis as what we were told by our teachers were absolutely different from what we could see in all the foreign books, catalogues and magazines. I started to deal with this chaos or void in the system with the work 'Leap into the Void, after 3 seconds' after the work of Yves Klein which depicts an artist leaping out of the window and the very moment of him being suspended in the air. To contextualize his work in my version which depicts the same scene but 3 seconds later the artist i.e. me no longer in between the ground and the sky but smashed to the pavement which is a fairly dramatic illustration of the conditions in the period around 2004. The void was typical of the non-existing Romanian art scene as back then, from one year to another several Romanian institutions that had previously promoted art disappeared. The Artists’ Union Gallery was closed down because its building was given back from the state to their original owners and other centres of contemporary art were closed down at about the same time. There was another small gallery of the Artists’ Union but they changed its profile and it became more like a souvenir shop. One day they had very good exhibitions and the other day they were selling gifts. It was not long after I graduated from the university and with this work I could capture the unstable situation of that period.

You work a lot with ideology, in your video 'Untitled (Santa Claus)' you show a mirror for the accelerated turn towards religion. Why have you approached the topic of religion with irony and humour, which is always, especially nowadays, a very slippery issue?

In Romania people are religious but not that radically. I found it really ironic that in 1989 right after we got rid of some absurd ideology people found religion to cling on. In the same time religious education was introduced in schools and Darwinism was taken out from the syllabus. Everybody turned to religion and the faculty of theology became extremely popular. Orthodox priests have beards and after the revolution a lot of bearded priests appeared so it was kind of exploding, and beards become iconic and somehow this Santa Claus beard seen in the video was easy to relate to. It was a very important video for us, it is not about making parody of religion. A good example that reveals the atmosphere back then can be shown that the actor (as I hired a professional actor for the role of Santa Claus, the others were friends) had bad conscience because of imitating a priest and wanted to go to a friend who was a priest to confess after shootings. So this was the actual context when I did this, it was my reaction of the growing importance of the church in people’s lives.

Exhibition opening at Ludwig Museum Photo: Ludwig Museum - Museum of Contemporary Art

One of your series of pencil drawings on view here was exhibited recently at Art Basel Miami. It is a pencil drawn archive of your work 'Communism Never Happened' originated as a text created in 2006, comprising letters fashioned from vinyl records of popular communist songs and its archive has been compiled over the years as the piece has travelled to numerous exhibitions where the eponymous slogan became, in some cases, the title of these exhibits, conferences or texts.

It is installed in museum vitrines and it forms a chronology of the recent debate regarding contemporary art in Eastern Europe, the relationship that artists have to the past, and the difficulty in reconciling the difference between communism as a promise of a better society and the various political regimes instated after 1989. With this work I wanted to show all my experience with the original work and all the reactions it received. The first time I showed it was in Warsaw: somebody took already on the second day the hammer and the sickle, in Prague somebody has stolen letter 'n' from the word 'never'. Five curators wanted to have it as their title of their shows and I tried to fill in these three vitrines with pencil drawn reproductions of all this documents. In the beginning I wanted to exhibit all the real pieces for documentation but then I changed my mind and copied instead the documentation by pencil because like this I thought it could be possible also intervene and manipulate it a bit. The original work is from 2006 so all the documents are not too old, still it was good to recuperate with these works.

How did the Miami audience react to this, and in general in what way does your works’ reception differ in and out of the former Eastern Bloc, as all your works belong more or less to our collective memory here in the region but how is it received in the U.S. ?

The fairs are always weird, especially in Miami. David Nolan Gallery applied with this project as they always have a booth there and they can apply with a section. It had long been in my mind so I did not do it for Miami ( ) but it was a nice opportunity to produce it. Now I am showing it here in Budapest and later on maybe elsewhere. As for the reception of my works I guess they are getting more and more the same, but of course there are things we do not know about the U.S. for example and vice versa. Not knowing the context well enough enables free interpretation, and I really like it when people are free to interpret and are not given full guidance. 'Communism Never Happened' has been interpreted in many ways like people asked whether we want to forget the past and have a new life or people like Gáspár Miklós Tamás took it as real as it had never existed in practice as it was supposed to be as it was more of a state capitalism. I cut the letters from the vinyl record of a popular communist songsfestival in communist time, which was the cultural mirror of what happened, and they had nothing to do with communism they were more like national events. This is why I cut this disc.

Last year you were one of the exhibitors of 'Past Continuous' group exhibition here in Budapest focusing on the socialist era, how could you relate to it?

When the young curator group visited Cluj and my works Dead Weights were chosen. I found these statues in a storage room in Cluj where they had been kept and they were a mixture styles: there were historical ones and also kind of abstract ones and were randomly selected, from the 20's till the 80's so it was a mixture of styles and trends like social realism and some trends that were copying the West. I had also shown their replicas in Basel but I don’t think anyone understood them as for them they looked only similar to something familiar but they could not relate to it. Of course here in Budapest it could become well integrated into the exhibition.

Ciprian Mureşan: All pages of Elaine Sturtevant book, 2014, pencil on paper, 93 x 142 cm Photo: Ludwig Museum - Museum of Contemporary Art

We can feel a shift from the earlier years where you used videos very often to the more recent period where many of your works as well as the ones exhibited here in Ludwig are manual i.e. pencil drawings.

My most recent works originate from European and Western iconographic values. From the Renaissance era I have copied many catalogues by hand and by pencil as I wanted to draw more. I wanted to become more manual again and I wanted to handle my work as a daily task. It has become a daily manual practice to copy meticulously works by Pierro della Francesca and Vermeer and from other artists I like. First I just did copies but of course later I started to explore and expand and work with these pencil drawings.

Here for example where we are sitting you can see two books shredded or that of the pencil copy of George Grosz’s book which is banded in a way that you can not see the drawings, or the Warhol catalogue from where I copied all its images onto one page. I am now more into series of works as I told you as I am trying to make drawing as a daily discipline and practice.

This method seems like your own way of digesting and processing images, is it your answer to the spread of images in visual arts and globalisation in general?

All this obsession of copying and drawing images comes from the fact that we are literally flooded with images and catalogues, so I felt the need to recuperate. Not long ago it was a big thing to have a catalogue let alone a comicbook in one’s possession. I became really enthusiastic for comics when I lived in Oradea because they were not common at all in Romania and my Hungarian friends received comicbooks regularly from Hungary. The same was the situation with art catalogues as they were also very rare, so information and images could spread very slowly. I remember times when it was Alexandru Antik’s “great privilege” to browse a Joseph Beuys catalogue, or to be well informed about the Viennese Actionism with Hermann Nitsch. Now the situation is radically different, and for me it is about trying to recuperate from this bulimic way of image consumption. I do not want images to be saved in my laptop’s memory but I want them to go trough my veins and my hands so that I have to consume and digest them in my own way.

For example here in Ludwig Museum you can see two drawings based on Pierro della Francesca’s work, one with normal graphite pencil and the other one with yellow felt tip, so I copy the same images twice. After one or two month I wanted to do a third one by memory but actually I was very bad at it, I made a very naive drawing even if I had drawn it previously two times in a very meticulous way. It is also not so much about learning but maybe more about consuming.

How informed you are about the current Hungarian cultural-political issues and the ones related to Ludwig Museum ?

I follow the Hungarian art scene so I am familiar with the works created here, I know the works by Little Warsaw, Miklós Erhardt, Róza El-Hassan and Dóra Maurer the most. With Miklós we are good friends we had some shows together at the Iasi Biennale and at Cluj as well.

My point with accepting this exhibition opportunity was that I know curator Krisztina Szipőcs for long time. Maybe I can say that also from the inside you can do resistance, shouldn’t be taken as a validation of the official politics.

Ciprian Mureșan (b.1977) lives and works in Cluj; from 2005 editor of IDEA art + society magazine. In 2014 he was guest professor at Hochschule für Bildende Künste Braunschweig. His recent personal exhibitions include: Obstacle Racing, Hochschule für Bildende Künste Braunschweig (2014), Stage and Twist (with Anna Molska), Tate Modern, London (2012), Recycled Playground, on view successively at FRAC Champagne-Ardenne, Reims (2011), Centre d'art contemporaine, Geneva (2012), and Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver (2013), n.b.k. - Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Berlin (2010). Selected group exhibitions: Six Lines of Flight: Shifting Geographies in Contemporary Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Sounds Like Silence, Hartware MedienKunstVerein (HMKV), Dortmund; The Freedom of Sound. John Cage behind the Iron Curtain, Ludwig Museum, Budapest (2012), Les Promesses du passé, Centre Pompidou, Musée National d´Art Moderne, Paris (2010); The Generational: Younger Than Jesus, New Museum, New York; The Seductiveness of the Interval, Romanian Pavilion, the 53rd Venice Biennale (2009).