Interview with Rafael Vostell, director of The Wolf Vostell Estate

We interviewed Rafael Vostell, Wolf Vostell's son and curator of his estate, at the opening of the exhibition "Boris Lurie & Wolf Vostell. Art after the Shoah" at Ludwig Museum, Budapest.

What's the greatest challenge in leading an estate that takes care of your father’s, Wolf Vostell’s legacy?

That's a good question. I think the biggest challenge is to make exhibitions like the one exhibited in the Budapest Ludwig Museum titled Art after the Shoah. To organize the exhibitions, to have all the works in mint condition and to find the right museums and the right people able to support these exhibitions.

In what state were your father’s pieces in when you started to work on the estate?

The truth is that my father was very well organized, which is very rare for an artist like him. When he passed away sadly young – being sixty-five years old – the family was in shock. We were in shock for almost a whole year and we couldn't really do anything because of it. But after a year, we started to establish the estate and to collect all of his works. Fortunately, we found the works in very good condition, and it was quite easy for us to create the in house catalog of all the works from all of his studios – because he had several studios in Europe: in Germany, France, and Spain. First we collected all of the artworks and brought them together into our storage in Spain to be able to start the estate.

We are very busy answering all the requests we receive from all over the world every day to send back photographic or textual materials. Then another big job is to keep the works alive, to have all of them in good condition because some restoration is always needed. The video works are a special challenge because these pieces include television sets that were produced forty or fifty years ago. And after such a long time the televisions don't work anymore. So we have to find solutions on how to restore them without changing the concepts or the visible idea of the artworks.

Has your impression on your father's work changed while working closely on the estate that preserves his life's work?

My father started to introduce me to his art practice and into the art world very early, when I was a little boy. So I grew up around his art and all his artist and museum friends. And now that he is not with me anymore I start to understand new things about him that I didn’t discover before. One thing I know: what I do is never boring because there are always new things to discover about his art.

I wonder if your upbringing, spending time with the close artist circle around your father had any long lasting effect on you, your personality or worldview.

Hearing the discussions between my father and his friends and seeing all these magnificent artworks was normal to me. It was also normal to be together with Al Hansen or Yoko Ono or other artists that my father had a good relationship with. I didn’t really care about them being famous or important in the art world. They were just friends of my family. But one thing is sure: I learned a lot from all the discussions that I heard between the artists about their point of view, about how they see life, society and what they think about politics. I learned a lot from these people.

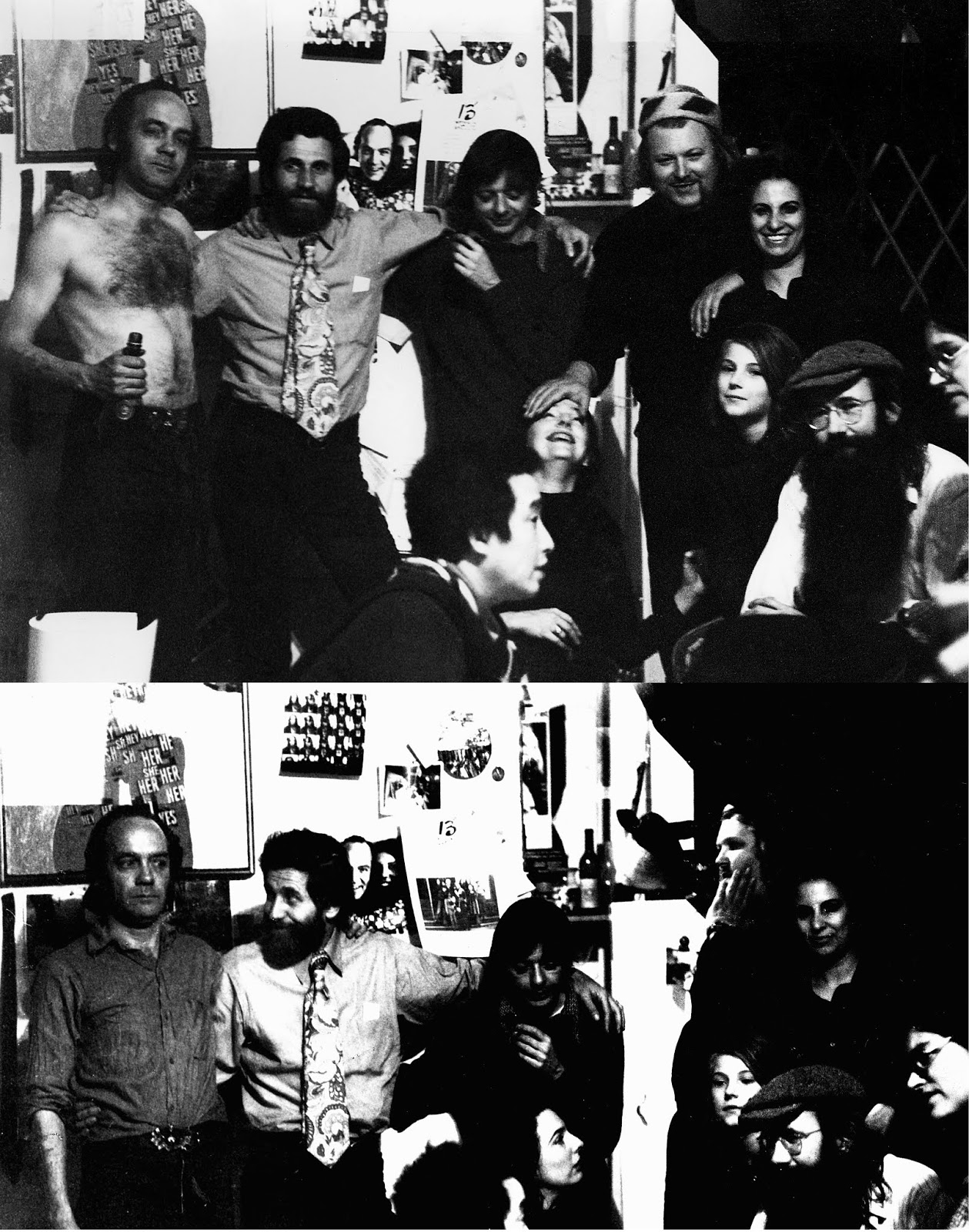

You mentioned Al Hansen, who sadly also passed away. I have found this group photograph taken in 1972 in Al Hansen’s studio in New York with you as a seven year old boy with Allan Kaprow, Joe Jones, Wolf Vostell, Mercedes Vostell, Nam June Paik, Charlotte Moorman, David Vostell, Geoffrey Hendricks, and Alison Knowles. Seeing this particular photograph and other materials on the Wolf Vostell Estate’s website it came to my attention very quickly that your father had a spirited and dynamic social life. How can the foundation keep this quite dynamic legacy alive?

My father did an incredible thing during his life: he collected everything and never threw anything away. He kept every sheet of paper. And then he founded the Vostell Archive that he called the Wolf Vostell Happening and Fluxus Archive. This archive is now at the Museo Vostell Malpartida in Spain. Here we can find everything about the art of my father, his friendships with other artists just because he kept all his letters, postcards and notes – sometimes he created notes even after having a phone call with somebody. The archive exists thanks to my father, and this legacy is crucial. The next step is to make the digitalization and to have it available on the internet. This will happen in the next couple of years.

How do you remember the friendship between Boris Lurie and your father?

I think it was a very deep friendship between Boris and my father for over thirty years. They met in '64 in New York for the first time and they kept in touch until my father passed away in '98. They kept in touch constantly writing letters to each other and having phone calls – and also, meeting in Europe and in the US. I think this was a deep friendship and an artistic connection. I also think that my father found Boris Lurie to be similar in the intellectual sense. Boris could really understand the ideas of my father. And I think the opposite was also true. Moreover, Boris was a wonderful person. I've met him several times and he was gentle and charming. In the exhibition created in Budapest you can see that we found almost a hundred letters that these artists sent to each other. And Boris always ends his letters with something caring like: “please send warm regards to your wife and to the two boys”.

Does the Vostell Estate take any part in keeping Boris Lurie’s legacy alive?

The Boris Lurie Art Foundation was founded after Lurie’s death by Gertrude Stein, art collector, gallerist and life long friend of Boris Lurie. I'm very happy and lucky to work as an advisor to the Boris Lurie Art Foundation.

Why do you think a joint exhibition of Boris Lurie and Wolf Vostell is important for people to see?

I believe it was principal to show the artistic parallels between Lurie and Vostell. And if you take a walk in the exhibition you can see that they spoke the same artistic language. That's why we did this European tour exhibition. The travelling exhibition first was shown at the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, then at the Kunsthaus Dahlem in Berlin and the Ludwig Museum Koblenz. The building of Kunsthaus Dahlem was by chance the former studio of my father so it was a nice coincidence that the works returned to the place where they were produced. The Ludwig Museum in Budapest is the fourth and last stop of this traveling show. We almost had the same works in all the four shows, but every show looked completely different. I found it interesting to see how the space of a museum can change the character of an exhibition.

Boris Lurie & Wolf Vostell. Art after the ShoahLudwig Museum, Budapest

31. March, 2023 – 30. July